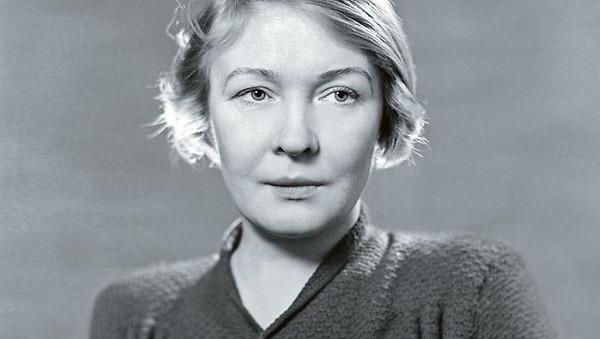

During the Siege of Leningrad in 1941, Olga Bergholz became a voice for the citizens trapped within the city. Reading her powerful poetry and flowing speeches over the radio waves and through loudspeakers, she captured with honesty the brutal reality of the Siege – including life, death, starvation, and the horrors of war. Not only did Bergholz use poetry to speak candidly about human suffering, but she used her writing to affirm the citizens’ right to suffer without feeling demeaned.

In 1910 Bergholz was born in St. Petersburg, Russia. She spent her formative childhood years in a home in the well-to-do Nevsky District of St Petersburg. Her father, Fyodor, a Russian-German, worked as a surgeon. After the October Revolution in 1917, Fyodor was recruited by the Red Army to work as a doctor on a hospital train. Bergholz’s mother, Maria, a Russian, tended to their children. Bergholz younger sister, Maria, later became an actress of the Lenin State Theater of Musical Comedy.

In 1918, the Russian Civil War forced the family to Uglich, a smaller town along the Volga River where Soviet power had been more firmly established the previous year. There, the family lived in one of the city’s several monasteries, repurposed as communal housing by the communists, until 1921.

Once Bergholz returned to her home-city, she entered the Petrograd Labor School which she graduated from in 1926. As she grew, Bergholz was known for her diligence, keen ability to observe, and her talent for conveying her thoughts, and opinions, in poetry. Bergholz’s love for writing was supported by both her parents.

Having grown up during the Russian Revolution in a household that supported the Bolsheviks, Bergholz too was a supporter of the Communist Party. She joined the Komsomol – a political youth group in the Soviet Union – at the age of 14. Her early poetry depicts the excited spirit of the time and what an exemplary Komsomol family should look like. For example, in her poem “Bail” (1933), she writes: “if it is necessary only – again and again / we will give all the youth – / for our / Republic.” Bergholz believed the communist philosophy that men and women would have to fight and struggle before the transformation to a completely communist society would be achieved. This struggle, however, would be worth it as all citizens would be equal and live in peaceful co-existence. Bergholz was willing to sacrifice anything, even her youth, to secure the radiant future for coming generations.

After the Russian Civil War, and the passing of Vladimir Lenin, Bergholz’s father passed her poetry depicting her “weeping about the deceased dear Lenin” to factory newspapers. She was published in the Red Weaver in 1925. Later in the same year, Bergholz published “Pioneers” in Lenin’s Sparks which depicted the growing strength of the communist movement and its supporters. These poems were published as part of the Communist’s general and widespread efforts to teach communist ideals to the citizens of the Soviet Union – many of whom at that time were still unfamiliar with them.

While Bergholz wrote for multiple Soviet publications, she also undertook factory work. She sought to show the communist ideal that everyone in a society should labor – and that women could work just as hard as men and should be entitled to all the same rights.

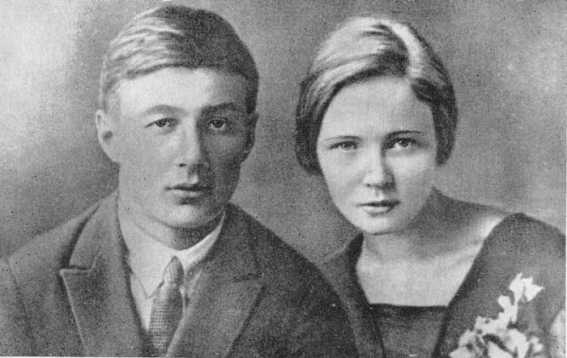

Following the publication of her poetry, she joined a youth literature group called The Shift, where teenagers practiced writing poetry with masters of the trade such as Eduard Bagritsky, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Joseph Utkin. It was in this group that Bergholz met Boris Kornilov, her future husband. Kornilov was another Soviet era poet who later became known for writing the words to “The Song of the Meeting” which was used to open morning radio broadcasts throughout the Soviet Union.

In 1927 both Bergholz and Kornilov entered the State Institute of Art History and in 1928 the pair married and, that same year, welcomed a daughter named Irina.

The State Institute closed soon after. It was later reorganized as part of the Leningrad Branch of the State Academy of Art History – part of the USSR’s efforts to vertically organize all branches of the state during that time. During the reorganization, Bergholz transferred to Leningrad University.

While at Leningrad University, Bergholz worked for Chizh, a children’s literature magazine where she wrote short stories and poems. With this experience, she published Winter-Summer-Parrot in 1930. This poetic story was an endearing tale of a girl who was not properly dressed for the winter weather. Although it was a small picture book, it signified an important stage in her creative career, as it was Bergholz’s first separately published work. In the same year Bergholz graduated from the philological faculty of Leningrad University.

Upon graduating, Bergholz was sent to Kazakhstan to work as a journalist for the Soviet Steppe, a newspaper that appealed to the diverse groups of people that made up the Soviet Union. During this period Bergholz divorced Kornilov and married Nikolay Molchanov. After returning to Leningrad with her second husband, Bergholz began working as a journalist for Electric Power, a newspaper owned by an electric power plant.

The 1930s began a time of personal tragedy for the poet. In 1932, Bergholz gave birth to her second child, her first child with Molchanov, a daughter named Maya. A year later, their daughter passed away following an illness. Bergholz’s first daughter, Irina, then died in 1936 due to a heart condition. Her feelings of despair were expressed in books of poetry she published during this period of hardship: The Out-of-the-way Place (1932), Journalists (1934), Night (1935), and Grains (1935).

As her poetry turned darker, Begholz was swept up in the Stalinist purges. While the fact that she was no longer focused as intently on spreading communism and depicting a glorious future for the communist state likely had something to do with this; the fact that she protested as many of her friends and acquaintances were targeted also made her a more likely target.

Begholz lost her membership in the Communist Party in 1937, after herself being charged with “unreliability.” She was expelled from the Union of the Soviet Writers on May 16 of the same year. Her ex-husband, Kornilov, was criticized in newspapers as an alcoholic and “antisocial” and soon after arrested, tried, and exiled to Siberia for his alleged participation in an anti-Soviet Trotskyist organization. Before he could leave, however, he was fatally shot.

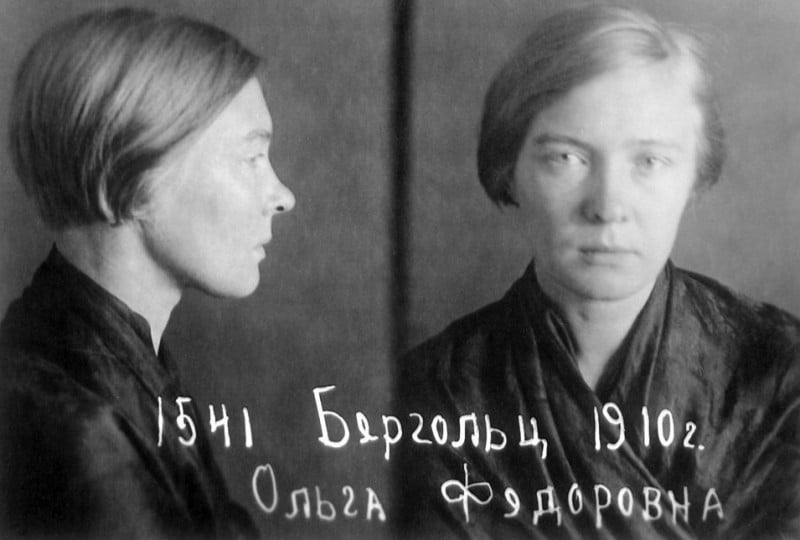

Begholz worked to restore her membership in the Union, which she received again in July, 1938. On the 13th of December, 1938, however, Bergholz was arrested by the NKVD, charged with “connection with enemies of the people” and “counter-revolutionary activities.” She was pregnant with her third child at the time. Beaten and tortured during her interrogation, Bergholz gave birth to a stillborn child.

While imprisoned, she wrote several poems that would not be published until the “Khrushchev Thaw.” One poem entitled “Trial” stands apart from the rest. In this poem she describes how something she loves “will start to bring pain. / Your friend – without blame – / will come a werewolf / […] You’ll be by him defamed.” The werewolf in this poem stands as a symbol of the distrust of certain officials and subsequent harming of loyal subjects.

In 1939, Bergholz was released, exonerated of her charges, and restored as a Community Party member. Bergholz stated in a diary entry after being released that “there was something wrong with the people [the NKVD who mistreated her in prison], not the idea of communism.” She believed that the Communist government she had worked so hard to help build was being taken over by people working for their own interests.

In September, 1941 the 900-day siege of Leningrad by the Nazis began. Whilst trapped in the besieged city, Bergholz spoke almost daily on Leningrad Radio, reading both recent news headlines as well as her own poetry. Her experience with confinement paired with the uncertainty of how long the suffering would last allowed her to create poetry the citizens of Leningrad could relate to.

Bergholz’s interest in working through personal trauma by writing poetry is evident in her poem “Homeland” which was published in 1939. In this poem she writes of her imprisonment: “Do not tempt my trust. / I carried it through the dungeon / […] deprived of sleep almost drove crazy. […] I speak with you as an equal / with equal, – / in free and brutal language.” The poem also demonstrates Bergholz’s acute awareness of the power of her “free and brutal language” to spread her feelings and connect with a larger audience. The poem also shows Bergholz’s feelings about artistic repression, by emphasizing the words “free and brutal language,” Bergholz, in fact, demonstrates her distaste for state censorship and her desire to use poetry to spread the truth.

Similarly, when Bergholz spoke to the people about the siege on Leningrad Radio, she spoke without fear of being censored. Each day, she pushed the boundaries of what could be said in public, constantly navigating between the brutal and ugly reality of the siege and the heroism that grew out of it that the authorities more preferred to focus on. For example, in her poem “The February Diary” which was read live on air, she writes of the incomprehensible pain of the citizens, but also offers listeners hope: “We already cannot find our sufferings / no measure, no name, no comparison / But we are at the end of the thorny path, / and we know that the day of liberation is near.” She is also honest about the situation the listeners are in, admitting in the same poem that she too is a subject of this seemingly endless suffering: “What kind of words could I find, / I, too, am a widow of Leningrad,” referring to having watched her second husband starve to death in 1942.

In March 1942, Bergholz herself was starving and suffering from dystrophy, in which the body’s tissues and organs begin to waste away. Despite her demands to stay, her sister and friends evacuated her to Moscow on the Road of Life, an ice road that was used when Lake Ladoga froze and provided the only access to the besieged city of Leningrad. In April, after receiving medical treatment in Moscow, Bergholz returned to Leningrad to continue her work on the radio. Shortly after, she married Georgy Makogonenko, a literary critic who also acted as a radio host during the siege.

In January 1945, Bergholz and Makogonenko released 900 Days, a “radio film” that was created using fragments of sound recordings including a metronome, excerpts from Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, announcements of danger, and people’s on air speeches. Despite the authenticity of 900 Days, it was criticized by composer A. Prokofiev, for making “to sound in verse exclusively the theme of suffering,” rather than concentrating on the heroic actions of the army and citizens. In a poem Bergholz responded to this criticism by writing: “And even those who would like to smooth everything / in the mirror timid memory of people, / I will not forget how the Leningrader fell.” Bergholz continued to be open about her memory of the siege by writing a screenplay, later adapted to the stage, entitled Born in Leningrad and an elegy, In Memory of Defenders in 1944 with her husband, Makogonenko.

Bergholz also worked to restore her ex-husband’s reputation. In 1956 she published an anthology of his works and, in January 1957, he was posthumously rehabilitated due to lack of evidence of his crimes against the Communist Party.

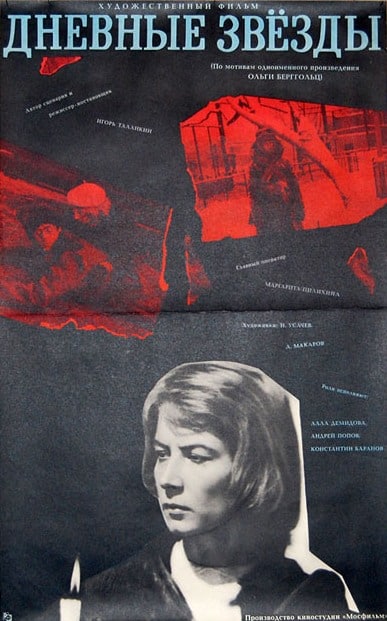

In 1959 Bergholz experimented in literary non-fiction with the release of Day Stars, an autobiographical novel about the siege. Internationally renowned director and writer Igor Talankin adapted Bergholz’s autobiography into a film of the same name in 1968. At the beginning of the film Bergholz is depicted by actress Alla Demidova, is shown as conflicted, saying: “Mother worries, grieves / What should I write my distant mother? / How to reassure her / to lie?” By the end of the monologue, however, Demidova’s Bergholz shows no fear and decides not to protect her mother but to tell the “truth.” This decision is seen throughout the film, as her serious and inspiring voice can be heard on the radio speaking of wartime tragedies.

The candor in which Bergholz expressed herself in poetry is often compared to that of fellow poet Anna Akhmatova. Akhmatova is most known for her poem Requiem which depicts the pain of ordinary people during the Soviet terror of the 1930s. Her style, like that of Bergholz, is characterized by its emotional restraint and honesty. One poignant line of Requiem reads: “Now all’s eternal confusion. / who’s beast, and who’s man? / How long till execution?” This poem reads similarly to Bergholz’s aforementioned poem “Trail” where a werewolf awaits the innocent. In another diary entry, Bergholz calls Akhmatova her “muse” and further states: Akhmatova is the “pride of Russian poetry.” The pair had more than their poetry in common; they were both censored and arrested in their lifetimes.

Bergholz’s lasting legacy is evident. She was a survivor – someone who refused to abandon ideals and truth in the face of severe repression and opposition. She also pushed others to survive in even the worst of circumstances. This included those close to her; in a diary entry, Bergholz’s sister Maria noted that: “she [Bergholz] forbade us from getting lice, telling us to wash our hair even when there was no warm water and it was 40 degrees below zero outside. I think Olga meant for us not to fight against lice, but for the whole idea of surviving.” It also included those who listened to her radio show during the Siege of Leningrad and those who still remember her cutting-edge broadcasts today. Despite repression, she also maintained her faith in communism and was eventually, in 1967, awarded the Order of Lenin, the highest civilian decoration bestowed by the Soviet Union.

On 13 November 1975 Olga Bergholz passed away in Leningrad. She was buried on the Literary Bridge in Volkovsky Cemetery in St Petersburg.

Her memory lives on at the Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery, the resting-place built to hold the 470,000 victims of the Siege of Leningrad. Here, her words are engraved on a cement wall, which reads: “No one is forgotten, nothing is forgotten.” Bergholz, too, will not be forgotten. The strength she had in life will forever be reflected in her poetry, which was the personification of hope in a dark time in Russian history.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2R60VI56JRA

Olga Bergholz reads her poem “Нам от тебя теперь не оторваться” (1963)