Gori, located a ninety-minute drive from Tbilisi, may not catch a visitor’s eye at first. However, the town is forever cemented in history as the birthplace of one of the most well-known leaders in world history: Joseph Stalin. Born Ioseb Jughashvili, Stalin spent the first sixteen years of his life in Gori. While Gori hosts a long and interesting history that spans centuries, the Joseph Stalin State Museum is now the main attraction.

The museum is dedicated to the life of Stalin and shows his participation in world history from his birth until his death. In addition to information on Stalin’s life, the museum also contains many artifacts from Stalin’s personal collection. Controversial in its portrayal of the late Soviet dictator, the museum is one of Georgia’s best-known and is well-worth a day trip from Tbilisi.

A Brief History of the Stalin Museum in Gori

The museum began when Stalin’s birth house was converted into a small memorial museum in 1937, during the height of Stalin’s reign. Construction on the rest of the museum began in 1951, as Stalin’s health was failing. It was officially opened in 1957, four years after Stalin’s death, and, interestingly, one year after the process of “de-Stalinization” had been begun by his predecessor, Nikita Khrushchev.

According to the official website, the museum complex was designed by the Georgian architect Archil Kurdiani, who was given free reign by the government to create an impressive structure to honor the late Soviet leader. The architect went appropriately, if predictably, with the architectural style that Stalin helped create and now bears the name “Stalinist.” Clean neoclassical lines are highlighted by columns and embellished by ornate balconies, porticos, and other elements. The interior is decorated in a manner also common to the buildings Stalin personally approved: luxurious red carpets, marble floors and walls, arches and curved central rooms, and a large glass chandelier.

The museum has been open continuously since its opening, save for a period in 1989 during the Soviet collapse which saw considerable instability in Georgia. Today, the Joseph Stalin State Museum is officially recognized as a cultural heritage monument in Georgia and is funded and protected by the Ministry of Culture and Monuments of Georgia.

The House Museum and Train Car Museum

The Stalin Museum has exhibits both inside and outside. The first sight coming off of the street is Stalin’s aforementioned birthplace, a small brick house where his parents rented two rooms and from where his father worked as a cobbler. The house is immortalized under a massive roof held up by classical-style columns and adorned with communist symbols. This is the house’s original placement and one can imagine the whole neighborhood of such houses, where Stalin’s childhood friends and their families once lived, that were demolished to make way for this complex.

Other outside exhibitions include a monument of Stalin, one of the last standing in Georgia. It stands between the house museum and the front entrance. Stalin’s personal train carriage is also featured behind the main museum complex. Stalin was famously averse to flying on airplanes and traveled everywhere by armored train. The carriage on display was used to transport Stalin to the Tehran Conference and the Yalta Conference during World War II. While the rest of the outdoor exhibits are free to view, entering the carriage requires an extra fee.

Inside the Joseph Stalin State Museum

The main exhibits featuring the life of Stalin are inside the large building constructed in 1957. Upon entering, a visitor is greeted by a large marble staircase with a red carpet leading to a statue of Stalin at the top. The museum officially starts once you have ascended to the second floor past the gaze of Stalin.

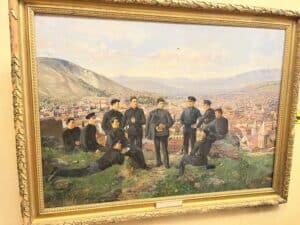

The first hall of the museum focuses on Stalin’s birth, adolescence, and revolutionary activity. It shows the old streets of Gori as Stalin and his family would have experienced it. Interestingly, it focuses much on Stalin’s days in seminary when he was studying for the Orthodox priesthood. Stalin entered into a local ecclesiastical school in Gori and was then recommended to move to a larger Orthodox theological seminary in Tbilisi. Instead of hiding Stalin’s religious background, the museum narrative embraces it and uses it to show how successful Stalin was in his studies despite his impoverished background. Also on display are poems that Stalin composed in his adolescence that show, presumably, his artistic and literary side. It was in these formative years that he began to learn about communist ideals and gain an intellectual formation.

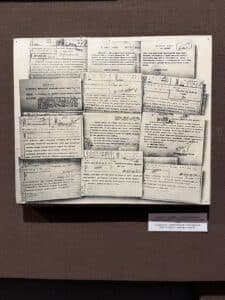

The hall ends with an introduction to Stalin’s time as a “professional revolutionary”- as titled by the exhibit. Here we are told of Stalin’s escapades and rise to power as one of the top leaders of the Bolshevik Revolution. Interestingly, there are no mentions of Vladimir Lenin’s worries about Stalin’s power at the end of his life. Instead, the exhibit portrays Stalin as a loyal comrade of Lenin with photographs of them spending time together and with letters where Lenin extols Stalin’s leadership. Thus, Stalin is portrayed by the curators as the true successor of Lenin who continued his legacy.

We then enter the second hall, portraying his successes as the leader of the Soviet Union. Displays show his effectiveness in collectivizing and industrializing the Soviet Union. He is also shown with many party officials — that he would later purge. None of the negative or violent events of Stalin’s life and rule are portrayed here: the dark sides of collectivization, the Holodomor, the Great Purge, the mass social displacement – this is all omitted here, and instead, there is a canvas with citizens’ letters thanking Stalin for his guidance. It provides the view of him as one who graciously improved the lives of Soviet citizens.

The third hall takes us to an even bigger story of triumph: Stalin’s leadership during World War II. Starting with the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 (and thus skipping the diasterous Soviet-Nazi non-aggression pact of 1939), the exhibit follows the heroic fight of the Soviet people under Stalin. The displays are dotted with propaganda posters, images of areas under Nazi occupation, and photographs of the Soviet military, with one showcasing Soviet soldiers kneeling for an oath to Stalin at his birthplace now displayed at the museum. The last exhibits show images of the triumphant Soviet people and includes a text wall with quotes praising Stalin’s leadership from other Allied leaders, major foreign Communist leaders, and prominent Soviet figures.

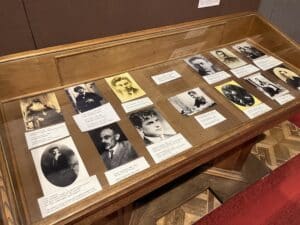

This hall also contains an exhibit on Stalin’s family life, including his wife and children, showing Stalin as a good father and grandfather with smiling pictures of his descendants. None of the family’s tenser dynamics are covered, such as his daughter Svetlana defecting to the US later in life, or his son Yakov’s attempted suicide (nor the famous story of Stalin making fun of him after he failed to shoot himself).

The fourth hall perhaps most effectively encapsulates the reverent aura surrounding Stalin that the museum seeks to convey. The only exhibit in the entire hall is the sixth copy of Stalin’s death mask, elevated on a marble surface and surrounded by marble pillars in a completely red room. It is a fitting end to the biographical portion of the museum. The way that the mask is displayed as a centerpiece conveys a sacred atmosphere to glorify the legacy of the late Soviet leader.

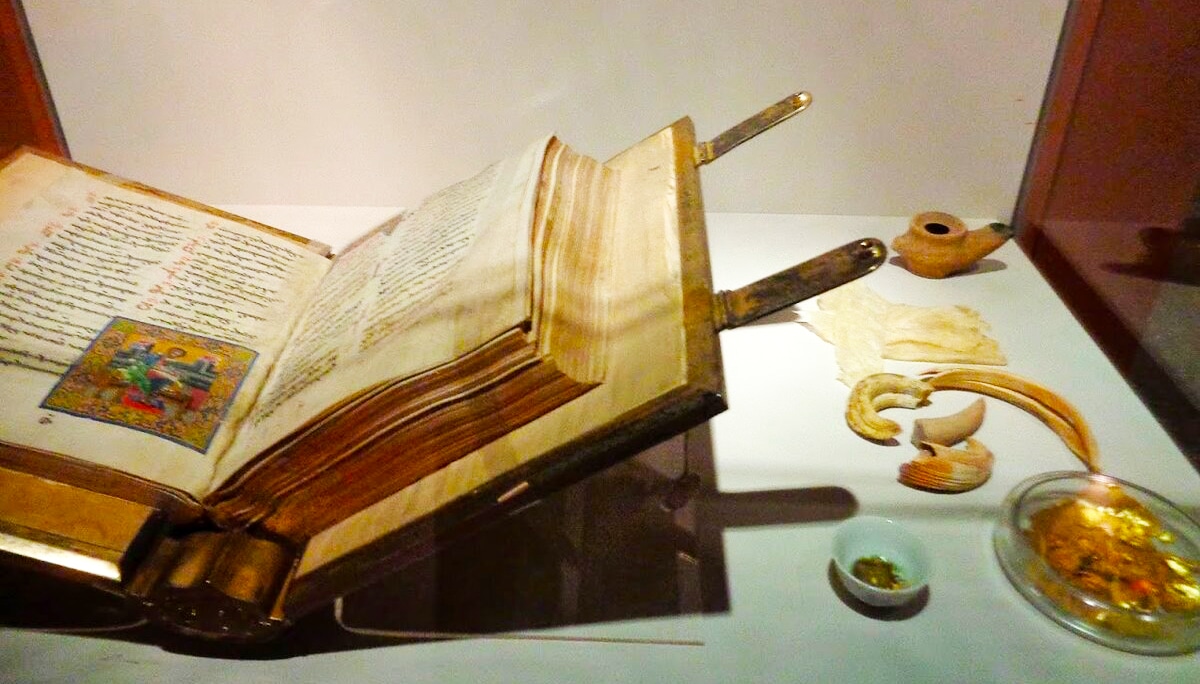

The rest of the museum features artifacts and personal artifacts in Stalin’s possession. The fifth hall displays some of the copious gifts that Stalin received from across the world. It contains everything from artisan furniture to fur coats and much more. The sixth and final hall is dedicated to Stalin’s personal effects: his famous World War II Marshal uniform and service cap, tobacco pipes, a handcrafted wooden casket from his son, and a recreation of his personal study.

The rhetoric of the museum seeks to extol the positivity of Stalin’s reign, and its bias largely lies in the omission of the negative aspects of Stalin’s tenure. If someone came into the museum knowing nothing of Stalin, they would see him as a man of ingenious wit and harmonic relationships who rose from a poor upbringing to be the leader of a very successful socialist state.

When I went, I only saw two exhibits that challenged the sympathetic rhetoric of the museum. In one of the first halls, there is a long table dedicated to Georgian victims of Soviet oppression – including writers, artists, and religious leaders. However, it was obvious that the exhibit was not original to the museum and was later inserted almost as a post-it note to remember repressed Georgian national figures. There is also a room under the main staircase on the first floor dedicated to the history of repressions under the Soviet Union with the testimonies of victims and a reconstruction of a prison cell. The exhibit also features images and victims of the 1992-1993 War in Abkhazia.

But while these two exhibits exist, they do not at all fundamentally change the original structure of message of the museum. The pro-Stalin rhetoric remains potent, especially since a few steps from the room dedicated to Georgian victims is the museum’s gift shop which contains postcards, t-shirts, and cigar lighters with Stalin’s face printed on them. For context, it should be mentioned that the political situation around Stalin’s memory is complicated in Georgia. Under the USSR, for many Soviet Georgians, the fact that their leader was an ethnic Georgian was a source of pride. This view was especially challenged after the 2008 Russo-Georgian War when Gori was occupied by the Russian Army. In fact, it was after this conflict that the aforementioned exhibits to Georgian victims were added, as there was a popular desire to reexamine the rhetoric of the museum. Yet for many older Georgians, sympathy for Stalin remains – especially for older residents of Gori. As such, the museum remains a museum piece itself – reflecting how Stalin wanted to be viewed by the people rather than providing as a critical and holistic examination of Stalin and his legacy.

Planning Your Visit

The museum is accessible to a foreign tourist. Aside from the halls featuring personal objects and a few possessions scattered elsewhere, a majority of the exhibits are only made up of photographs and copies of quotes or documents. Each plaque has a Georgian and Russian description on it, and there are English translations for the main exhibits. In addition, it is possible to hire tour guides for the museum who speak English and other languages for an extra fee. While I did not take a guide, I was told by multiple people in Tbilisi that the tour guides there are notorious for portraying Stalin in a positive light and extoling his leadership. However, this would only be in line with the experience that one has at the museum even without a guide. Taking a guide could be a worthwhile experience for those seeking to learn about the concept of historical memory and rhetoric. The museum is an indispensable resource for this, especially if one is already knowledgable of the era and can thus know where to take the information presented with a grain of salt.

You Might Also Like

Fortress of Gonio: Georgia’s Roman Heritage

The Fortress of Gonio, located in Adjara, Georgia, is an ancient Roman fortification dating back to the 1st century AD. A strategic point along the Black Sea coast, over the centuries, it was expanded and fortified by the Byzantines and Ottomans. Today, the well-preserved remains of Gonio Fortress stand as an important cultural and archaeological […]

The Batumi Archeological Museum in Georgia

The Batumi Archeological Museum is centrally located on the main highway that runs through the city. It is a two-story stone building that houses a plethora of artifacts from Georgian excavation sites, bringing to life the story of the local people and their connections to European culture. History and Founding of the Batumi Archeological Museum […]

The Simon Janashia Museum of Georgia (The National Museum of Georgia)

The Simon Janashia Museum of Georgia is a great first stop in Georgia for an essential overview of the country’s place not only as a small country that has long lived at the crossroads of great empires but also as a modern nation with a layered millennia-old history unto itself. The museum shows the highlights […]

The Tbilisi History Museum

The Tbilisi History Museum is a quick peak into the city’s 19th century past that helps solidify its importance as a commercial hub at the cultural crossroads of the Persian, Ottoman, and Russian empires. Housed in a historic building with other worthwhile museums and telling its story through models, life-size dioramas, historic photographs, and other […]

Igrika Crafts: Interactive Art in Tbilisi, Georgia

Igrika Crafts is a family-run art studio based in Tbilisi which specializes in block-printed textiles with traditional Georgian folk motifs. They graciously offered to organize a block-printing workshop for my fellow SRAS Tbilisi study abroad participants to teach us more about their art as well as the Georgian history, culture, and folk art which inspires […]