Throughout my stay in Poland, I have found that one of the most pressing concerns in society is the role the Catholic Church plays in state and public affairs. A Croatian theater director, Oliver Frljić, known for creating theatrical productions that focus on pressing contemporary problems in specific countries, has now produced a play here in Warsaw titled Curse (“Klątwa,” pronounced “klOHntva” in Polish), currently showing at Teatr Powszechny. The play has sparked a major public debate on not only the Catholic Church, but also on issues of artistic freedom.

Polish voters have recently given the conservative and distinctly pro-Catholic Law and Justice Party (PiS; initials taken from its Polish name), a strong ruling position in the Polish government. PiS has responded with very swift and radical social reforms. More liberal elements of society have protested fiercely against many of these. For instance, strikes and protests were held across Poland against a recent decision to ban abortion with only three exceptions. As a result of the ban, if Polish women want or need an abortion, they must travel — very expensively — to Germany or Sweden. Additionally, the government is also beginning to work on eliminating birth control options for women.

These pro-life changes are largely connected to the Church and its values, which have a very strong presence in Poland. Many feel that the Church is owed a debt for assisting them in the struggle over communism. Others feel that the Church, with its strong historical ties in Poland is a natural part of what it means to be a Pole now.

The Church’s strong position has made any discussion of the Church’s role in society a political flashpoint, including even discussion of the rights of victims of sexual abuse committed by Catholic Church clergy. Critics cite this when stating that not a single victim has received justice.

All of this for me hits very close to home. I grew up in a family that followed the Polish Catholic tradition very closely, in a small town in Michigan dotted by many beautiful Catholic Churches. Most of my family that has stayed in the Catholic Church since the abuse scandals remain devout, and refuse to discuss the issue of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. Wide social pressure on the Church, however, forced it to release the information they had already gathered on sexual abuse in the Church. So many in my town left the Church after that, that many of those many churches in my hometown closed, filed bankruptcy, and are now abandoned. But in Poland, social concern does not seem to have had such an impact; instead, the ruling party (PiS) dismisses sexual abuse claims, and even often gaslights the victims of these horrendous crimes.

It was within this context that I sat down, in Warsaw, to watch Oliver Frljić‘s powerful and controversial Curse.

The play is named after and based on drama written by the nineteenth-century Polish playwright, Stanisław Wyspiański. In his 1899 Curse, a village priest takes a young woman as a lover and has children with her out of wedlock. Suddenly, a drought occurs in the village, and the villagers, believing the drought to be caused by the young woman’s sins, decide to burn the children and the young woman as a sacrifice to please God and thereby end the drought. The priest, meanwhile, is not punished. For his modern-day Curse, Frjlic used this play as a philosophical framework for a creation that highlights how abuses of power by the Church, in form of sexual abuse, are protected by the state today, just as they were back then.

Frljić’s play summarizes the original in the beginning, and is a rather difficult scene to watch, as it consists of the young village woman being spit on, heckled by villagers, raped by the village priest, and forced to sacrifice the children she bore with him. This summary is introduced by the actors calling out to the early 20th-Century German playwright, poet, and director Bertolt Brecht, who was best known for drawing to draw the audience directly into the production in order to maximize the educational value of each performance. Much of Frljić’s performance uses Brecht’s tools of alienation, as well as shocking imagery, to try to push the audience towards a call for action.

Frljić’s actors ask Brecht for his opinion on how they may be able to reenact Wyspiański’s Curse from a contemporary standpoint. The reply they are given is that “Poland is the butthole of Europe” and under the jurisdiction of the Catholic Church, so they must go ask the Pope. A plaster statue of the Pope John Paul II is then dragged onto stage, and one of the actors performs oral sex on a plastic phallus attached to the plaster statue in order to gain permission. Throughout this scene, a Catholic sermon in Polish is played aloud for all to hear.

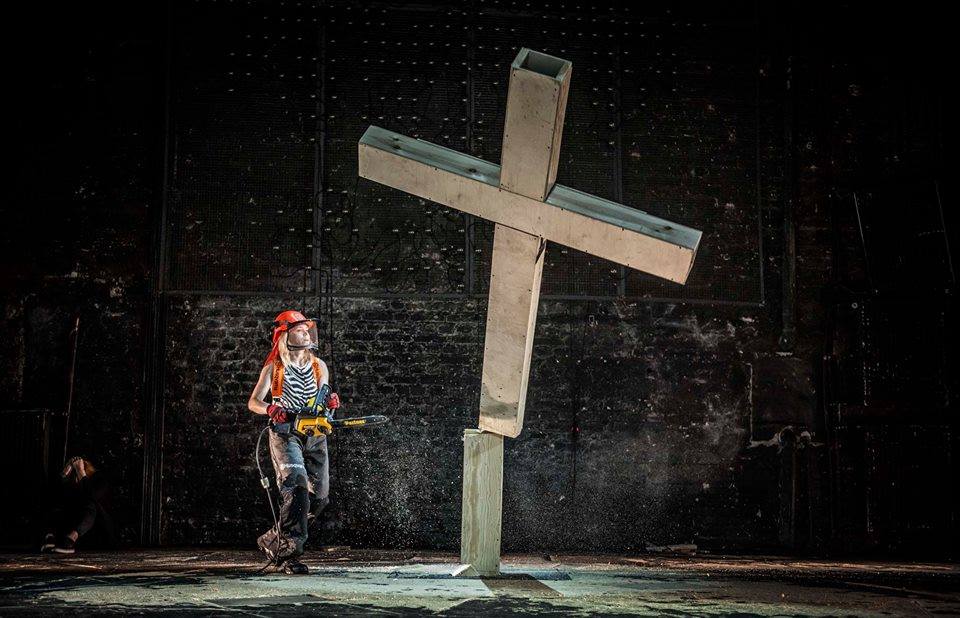

The scenes that follow this include, but are not limited to: the actors picking audience members to accuse of not being Polish (to highlight Poland’s overall xenophobia problem); an actor bringing a dog onto the stage to “sniff for Muslims in the audience” (to address Poland’s increasing Islamophobia); separate actors giving monologues about their experiences with abuse in the Catholic Church (though it is unclear if these are the actors speaking, or the director); the actors assembling guns out of various religious crosses by connecting them together; an actress giving a monologue about how she will have to leave the country to get an abortion (though again, it is unclear if it is the actress actually speaking as herself, or if this is the director speaking); and another actress (the same one who performs oral sex on the plaster statue of the pope) tests the boundaries of what can be said and cannot be said in the theater, by reciting the Polish law that forbids one to even speak of assassinating a Polish political leader, which contains language that it itself bans. The final scene consists of one of the actors sawing a cross in half with a chainsaw (yes, a real chainsaw is used on-stage).

This play is being attacked from many sources now, including by the now-pro-governmental public media and the state authorities in Poland. The controversy started when a pro-governmental activist took a video fragment of one of the scenes and leaked it onto the Internet, framing it within a context that does not take into consideration the issues it addresses: pedophilia and sexual abuse in the Catholic Church, as well as current debates over women’s rights. Instead, many voices in power are simply calling it “blasphemous” and calling the theater, actors, and directors to be prosecuted under a law established in the 1990s that protects people’s “religious feelings.” Oliver Frljić has since written a letter to Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission, regarding the attacks being made against him in the pro-government public media and the state authorities.

But the fact of the matter is that had the pro-government activist not leaked footage of the video, no one’s religious feelings would be offended, as before one goes to the performance, you must buy a ticket and receive a brochure that clearly informs you of the play’s content. No one is forced to go to the theater. When I went to see the play I most definitely received a brochure beforehand. Further, while a lot of these scenes were difficult to watch, the context they are put into does not imply “blasphemy.” If anything, taking responsibility and acknowledging past crimes and abuses may actually help the Catholic Church regain some of the support it has lost in recent years.

The attacks being made against Curse highlight much wider issues of freedom of speech and expression in Poland. Theater has always been an important platform for Polish dissidents, even under the domination of the Russian Empire, and under Communism, dissidents in the theater found ways to express their dissatisfaction and resistance. Protests, demonstrations, and marches continue at an alarming rate around Poland to address these issues and, most likely, theatrical productions will continue to address them as well.

I personally found this production to be a fascinating, if often disturbing, look at controversies currently facing Poland as well as my own life.

Below is a video of Oliver Frljić defending his theatrical production in English. It was posted by Teatr Powszechny.

Curse

Teatr Powszechny

Powszechny.com