As I attended my 20th class at St. Petersburg State University, an old woman waltzed into the room speaking rapid-fire Russian, waving theater tickets and emphasizing the words Fyodor Dostoevsky with much grandeur. My curiosity was piqued. The tickets were handwritten, the location of the theater obscure. In bold on the front of the ticket was written “B дом смешного человека” (In the House of a Ridiculous Man). I bought a ticket for myself and a friend, resolving to read the original story, which Dostoevsky had entitled “Cон смешного человека” (“Dream of a Ridiculous Man”) beforehand.

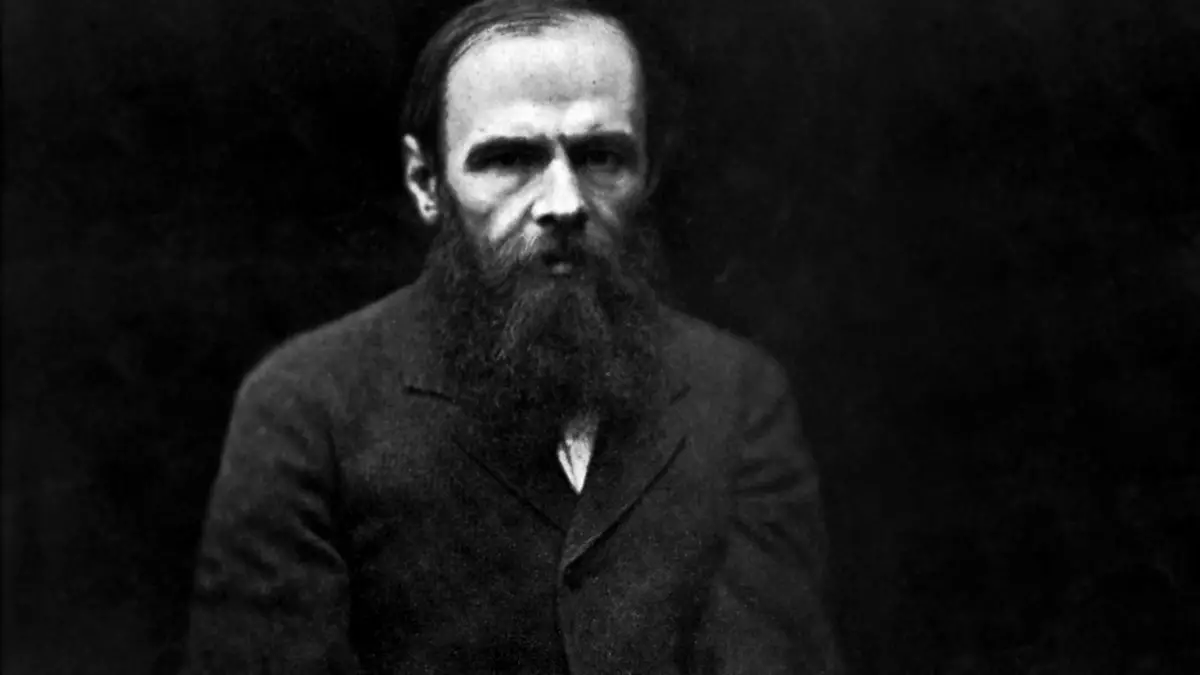

They say that Fyodor Dostoevsky’s works hold the key to the Russian soul. When I left for Russia in May, I promised myself that I would bring back something that was related to Dostoevsky, something that could not be found at home.

It was this strange coincidence that brought about the realization of my promise.

When we got to the theater, I was surprised to find the old woman waiting for us. She told us we were not to go into the theater, but that we would be going on a little field trip. Along with the nine other people of the audience, my friend and I followed her out of the theater entrance, and into a backstreet of Petrograd Island. It led to a dark and dingy apartment building where, we were told, the play was to take place. “Now don’t be surprised at anything you see here,” she warned as we abandoned the broken elevator to walk up the crooked stone steps. “All of you will get out alive.” As the old woman probably intended, her comment was more unsettling than reassuring.

We gingerly followed her as she stepped into a room that was even darker and dingier than the building’s staircase. As I passed through the Russian doors, a musty smell wafted into my nostrils and my eyes smarted from the dust in the air. When my vision had recovered, I beheld such a sight that it was necessary to rub my eyes again, this time in disbelief. The light of a single candle hanging from the ceiling revealed ancient couches covered in a velvet so worn from wear it shone, a warped mirror so laden with dust that it reflected only the most vague forms and an oddly shaped wooden trunk with a fur throw over it, sitting stubbornly in the center of the room. Black-and-white photographs of Russian aristocrats had been placed on the walls, where they seemed to scrutinize us with their pale, fierce eyes.

Our silence was broken when a joyful woman burst through the doors, singing a hypnotic Russian tune. She began dusting, her eyes meeting mine as if she were not looking at me at all but through me to the wall behind. She left as quickly as she had arrived, taking the lone candle with her and leaving us in complete darkness. It was then that we received the surprise we had been warned about.

No sooner had the singing lady left, than the trunk in the middle of the room began to move. There was some rattling, and then a big bang as it burst open and a man of huge stature emerged. He lit a match, bringing it up to his grizzled beard and bulging eyes, staring at us with haggard concentration. It was the melancholy, self-loathing protagonist of “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man.”

With wild eyes, he yelled deliriously in our faces, and the cries of the inhabitants of the apartment could be heard in the background. The audience began to grasp a sense of the horror that prevailed in everyday life for Dostoevsky’s most interesting subjects. The land of perfection in the character’s subsequent dream seemed beautiful but empty by comparison, and its innocence short-lived. Disillusioned, he wakes declaring that it is necessary to suffer in order to feel love and appreciate beauty. I was moved by the actor’s faith in the harshness of life, for I knew that it represented what was at the core of the stoic Russian spirit.

On the way home, I felt as though I was in a different world. I didn’t notice the glamour of the metro; I didn’t want to. I wanted to notice the people, to get a sense of their spirit of endurance. I sought that passion for life that has eluded the comfortable. I could not find it. My experience had been entirely within the boundaries of the play, and I had nothing to show for it. I left the apartment in a state of near shock, leaving both the ticket and the program behind. I would have liked to remember the names of those who put on that unforgettable production. For every culture has a soul, and it is up to the imagination of the artist to express it.

This article was written by a Canadian friend to SRAS, Margie Marlin. It originally appeared in The Globe and Letters on Aug 23, 2004 under the title “A Dark and Dusty Peek Into the Russian Soul.” This is an edited version.

You Might Also Like

(includes current article)

The Dostoevsky Memorial Apartment Museum in St. Petersburg

The Dostoevsky Memorial Apartment Museum at 5/2 Kuzneckny Pereulok in St. Petersburg is dedicated to drawing a picture of the great Russian writer as a person with a focus on his work habits, on his concerns, and particularly on his family life. Even discussion of his greatest novels is presented within the context of telling […]

Crime and Publishing: How Dostoevskii Changed the British Murder

A few words on this book: Described by the sixteenth-century English poet George Turbervile as “a people passing rude, to vices vile inclin’d,” the Russians waited some three centuries before their subsequent cultural achievements—in music, art and particularly literature—achieved widespread recognition in Britain. The essays in this stimulating collection attest to the scope and variety […]

The Hero of Cana: Alyosha’s Ode to Joy in The Brothers Karamazov

Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov opens with a particularly unsatisfying note. The fictional narrator declares in his “From the Author” that the hero of the book is Alexei Fyodorovich Karamazov. Quickly following this declaration is a confession: “To me he is noteworthy, but I decidedly doubt that I shall succeed in proving it to the reader” (Dostoevsky 3). […]

Suicide as a Final Reconciliation of Conflicting Identities in The Brothers Karamazov

The function of violent death is complex in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov: it serves as the driving focus of the work, calls into question the many characters’ agency and morality, and provides a forceful resolution. At the forefront of the novel is the murder of Fyodor Pavlovich by one of his sons. Parricide is the […]

Rational Perversions of Love in The Brothers Karamazov: Spiritually Fruitless, yet Thematically Useful

In The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoevsky spends countless pages elucidating his ideal of love. Among his many characters, he offers complex portraits of two intriguing individuals, whose love does not quite fit his definition of this ideal. The Grand Inquisitor and, by extension, his creator Ivan, are often seen as simply hyper-rational characters who reject God’s […]