The State Museum of Applied Art and Handicrafts History of Uzbekistan provides an excellent introduction to Uzbek history and culture. Centrally located in Tashkent, it displays more than 7,000 examples of traditional folk art. These include a range of mediums from decorative glass to porcelain and fabrics, all dating from the first half of the 19th century to the present. Today, the museum draws visitors not only for the artworks on display but also for the museum’s traditional architecture, which features a layout and elements common to mosques and to late-19th century aristocratic households.

For anyone looking to do a bit of research before visiting, you can find the state museum catalogue here and find the audio guide here.

History and Architecture of the Museum

By Sevdora Eshnazarova

The first exhibition of applied art of Uzbek artists was held here in 1927. At the time, it became known as the “National Exhibition of Uzbekistan.” Over the years, the museum’s collection has grown with the addition of jewelry, hand-made embroidery, and carpets. In 1938, the collection gained a permanent home in its current building, a former palace of the Russian diplomat Alexander Polovtsev. In 1960, the National Exhibition was renamed the “Permanent Exhibition of Applied Art of Uzbekistan.” It gained its current name in 1997, when Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Cultural Affairs, which now oversees the museum, granted it the status of “State Museum of Applied Art.”

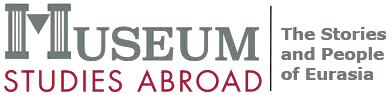

The palace that now houses the museum was built in 1870. The central hall is a traditional mehmonkhona, a word that roughly translates as “guest room”, and is meant for receiving visitors. Designed like a mosque, it is square-shaped with four columns and, along one wall, a mihrab, an indentation meant to help the faithful direct their prayers towards Mecca. However, the palace’s mihrab only plays a decorative role here – as it does not actually point towards Mecca.

The room truly awes its visitors and is a museum piece in and of itself. Its walls feature 200 ornamental motifs and 4 tockchas (niches), which are traditional to Islamic architecture with built-in decorative shelves to display ceramics. The fireplaces next to each of the tokchas are decorated as well and each topped with an onion dome. The two contemplative inscriptions above the doors are written in Persian but with Arabic writing: “The world is like a caravanserai with two doors, they enter through one, and they leave through the other,” reads one; “And every day there are more and more new guests in this caravanserai,” says the other.

Briefly on Silk Textile Manufacturing in Uzbekistan

By Lily Nemirovsky

Silk manufacturing techniques were first developed in China, but quickly spread westwards along the Silk Road, giving it its most widely recognized name. In Uzbekistan, silkworm rearing occurred in multiple provinces, as mulberry trees – whose leaves are eaten by silkworms – are drought resistant and can thus survive in environments as fertile as the Ferghana Valley and as dry as Khorezm. Women were traditionally in charge of the initial steps of sericulture (growing silkworms), which includes cultivating mulberry trees, collecting silkworms once they have grown and spun their cocoons, boiling the cocoons, collecting the silk from inside, and reeling it. After this point, men would twist the silk into thread, dye it and create the designs for the cloth.

A Visit to the Museum (Winter, 2024)

By Sevdora Eshnazarova

I visited the State Museum of Applied Art during the winter, which ensured a quiet space with very few other visitors on site. There were several traditional folk art pieces, including fabrics, embroidery, skullcaps, carpets, musical instruments, miniatures, ceramics, jewelry, and much more. Each artifact had a short caption, and there were posters explaining various categories of displays. With free WiFi available from the museum, free audio tours were accessible in Russian and English with a QR code provided at the ticket office. For those wishing to gain more insight into the artworks, the audio tour was the perfect opportunity. Although closed during my visit, there was a gift shop with souvenirs near the exit.

The museum can be separated into five sections. The first section focused on embroidery, including hand embroidery and machine embroidery, national clothes, duppi or skullcaps, carpets, and a small section on musical instruments. I particularly enjoyed one machine-made suzani, which is a type of embroidery. Composed of the parts named “Spring”, “Motherhood”, and “Harvest”, it was captivating at first glance and fitting of its title. Machine embroidery was introduced to Uzbekistan at the end of the 19th century and quickly became a popular alternative for commercial craftsmen to time-consuming hand embroidery. From the red circles and black floral patterns on the border, one can tell this piece is from Samarkand, where that style dominated.

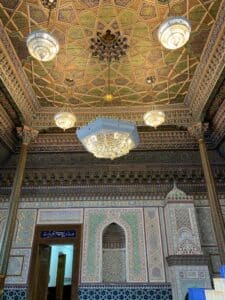

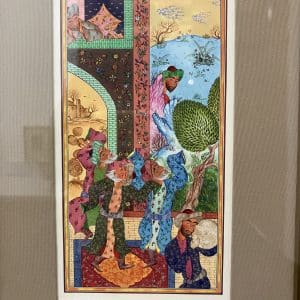

Exiting the fabrics section, one passes through the central hall to the oriental miniatures. These tiny paintings include a surprising amount of detail and decoration. Some depict scenes from popular folk stories, such as “Nasriddin Afandi” and “Xusrav and Shirin,” both popular with Uzbek children. The miniature of “Nasriddin Afandi’s Story” depicts him in a red hat and a wealthy man sitting on a donkey. This painting is exactly like the popular cartoon that was made of the story, which teaches children the value of money earned through hard work.

The many doors in the hall lead to rooms filled with ceramics, glass work, and clay whistles, which are considered national toys. Notable amongst them are seven decorative plates from the series “Seven Beauties” based on Alisher Navoi’s poem “The Seven Planets.” Each beauty represents a country or region: India, Iraq, Iran, Mongolia, Sogia, Fergana, and Kharezm. The last door in the miniature painting hall leads to several rooms with more national artifacts like jewelry, wood carving, painting on wood, metalsmithing, and lacquer miniatures.

Overall, The State Museum of Applied Arts of Uzbekistan is an excellent introduction to intricate and beautiful craftsmanship that Uzbekistan has been historically known for. It covers a breadth of applied workmanship, and is itself a prime example of 19th century architecture.

A Visit to the Museum (Spring, 2025)

By Lily Nemirovsky

I visited the museum out of personal interested while leading students to Uzbekistan for our Spring Break: Navruz in Uzbekistan program. The State Museum of Applied Art and Handicrafts History of Uzbekistan offers a vibrant journey through the country’s rich artistic traditions, showcasing the skill, heritage, and symbolism embedded in everyday objects. Its remarkable collections highlight centuries-old techniques passed down through generations. Most of these techniques and crafts are still practiced today and still a proud part of the modern culture. From the intricate embroidery of suzani textiles to the bold patterns of ikat fabrics, each exhibit tells a story of craftsmanship and cultural identity. This visit gave me a deeper appreciation for Uzbekistan’s artistic legacy and the ways in which these traditions continue to shape contemporary Uzbek life.

Suzani

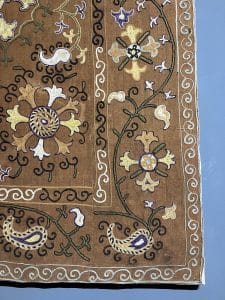

The first room showcases Uzbek textiles, mainly suzani embroidery and woven ikat clothes. Suzani is a type of traditional Central Asian embroidered cloth historically hand-sewn by women with silk thread. It can be found in many Uzbek homes as wall decoration, tablecloths, prayer mats, bed sheet covers, and more. Each region of the country claims its own special variation, but they all tend to include geometric plant and animal designs and multiple types of stitching, which help convey movement and texture. Common motifs include flowers, pomegranates, vines, and the sun & moon, many of which symbolize fertility. This hints at the special role suzani plays in wedding traditions, as part of the bride’s dowry and carrying out nuptial rituals. Many girls start preparing their dowry as early as age six, because, according to tradition, girls should learn ten types of embroidery for their marriage. The intricacy and magnificence of the embroidery is not only a direct reflection of the bride’s skill in the respected art of needlework, but also of her commitment to her future husband and family-in-law; one large suzani can take months of working stitch-by-stitch to complete. It is also a method of retaining knowledge and practice on the matrilineal side, as mothers often pass down their own mother’s teachings to their daughters. During the wedding ceremony, suzani plays multiple roles. For example, it can be used as a canopy held above the bride as she walks and greets her soon-to-be-husband during the kelin salom (greeting of the bride), as well as a hanging partition marking where the bride sat.

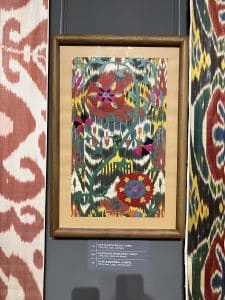

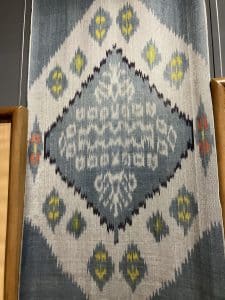

Ikat

Hanging between the suzani pieces are long strips of ikat cloth. Ikat is a woven fabric created with resist-dyed threads, which help keep the dye contained in the desired pattern. This technique has been used by cultures all over the world, but what makes Uzbek ikat stand out is the fact that artisans only dye the warp threads, not the weft threads, too, as they do in places like Indonesia and Japan. The local name for ikat is abr, which comes from the Persian word for ‘cloud’. The design resembles clouds reflected in the surface of a body of water. Historically, a loom made out of mulberry or walnut wood, called a dukon, has been used for ikat production. During the early Islamic period, ikat clothes were made from cotton, as the wearing of silk was condemned in Islam as a form of boasting one’s wealth. However, with time, silk was integrated into ikat production and became the most popular style of clothing not only for the upper echelons of society, but for commoners, as well. Recently, ikat has made its way into the high fashion world, where famous fashion designers such as Oscar de la Renta have incorporated it into their work.

Duppi

Duppi, decorated skull-caps, are one of the most popular types of headwear among Uzbeks. There are endless variations of duppi, categorized by region, age, gender, and occasion. The signature male duppi is a four-sided black cap with a white embroidered pepper symbolizing life and well-being on each side. Irises, tulips, pomegranates, cherries, roosters and pheasants are common on women’s duppi.

Chapan

A staple of Uzbek costume is the chapan, a quilted robe. Chapans are very practical and comfortable; they can be light for the summertime or thick and padded with cotton or camel wool for the winter. The sleeves are loose, allowing for layering underneath in the wintertime and air flow in the summer. Two slits on the sides facilitate walking, and instead of buttons or zippers, the robe is simply tied with a scarf called a kiyikcha around the waist. The colors and embroidery design of a chapan conveys information about the wearer’s societal status. For example, Green may be worn among peasants, while blue and purple suggest wealth. Some are even embroidered with gold-dipped thread. Another popular version are chapans made of silk in the ikat style.

Instruments

While not traditionally included in handicrafts, the Uzbekistan State Museum of Applied Arts shows how instruments can be an artifact not only of auditory beauty, but visual delicacy, as well. Each one is exquisitely decorated with engravings and bone, metal and mother-of-pearl inlays. Their basic geometric shapes strike a perfect balance between simplicity and elegance, and the sheen of the inlays bring out the deep hazel of the wooden body. The collection includes string instruments (rubob, tor, tanbur, dutar, gidjak), wind instruments (nay), and percussion instruments (nogora, doira). Although the oldest type, the rubob, is believed to have been around for at least 1,000 years, this decorated set of instruments is from the 20th century, demonstrating an innovative mix of ancient sound with modern technological and aesthetic techniques.

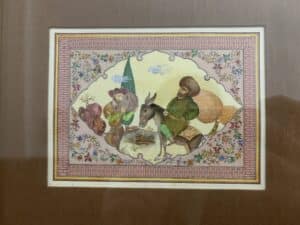

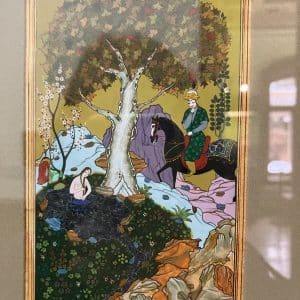

Miniatures

The art of local book miniatures began in the 10th century, when these paintings started being used to illustrate books and hung on the walls of the palaces of Khans. These were accepted as an exception to Islam’s prohibition of depicting human and animal figures in art and architecture, justified because they were used in a non-religious context. Book miniature production reached its pinnacle in the 14th and 15th centuries, when artists such as Kamoliddin Bekhzod worked in the Timurid Court and “perfected” the genre of Persian miniatures. Miniatures were painted on silk paper made from the bark of mulberry trees, and the paint dyes were made from natural materials, such as plant roots, onion peels, and berries. Bronze and gold leafing were also occasionally applied to bring the miniature to life. The process involved not only painters, but calligraphers and bookbinders, as well. Daily social life at the high court, hunting, fables, love, and war were the most common scenes painted.

Jewelry

Jewelry has been a part of Uzbek culture for millenia, especially for women and girls. Silver and gold provided structure for coral, mastic, turquoise, stained glass, river pearls, and other colored inserts and beads. Gold jewelry was reserved for women only, as men were forbidden to wear gold according to Sharia law. Some materials held symbolic significance, for example, turquoise for victory and coral for fertility. Other pieces had practical purposes, like those that had small cases with a pin cushion and sewing needles so their wearer could have them conveniently at-hand wherever they went. Tumors were gilded boxes inside of which lay a piece of paper with a prayer written on it to protect against the evil eye. They were fixed to a piece of clothing in areas of the body that were deemed the most vulnerable, such as under the arm or on the chest. Chochpopuk or sochpopuk were tassels that decorated women’s long braids. They could be made of chain-linked silver coins or cotton string and were punctuated by a tassel. One of the most recognizable traditional Uzbek jewelry pieces is the tilla-kosh, which means golden eyebrows. It consisted of a double-arched silver or gold plate that sat on the forehead and was topped by crown-like beaded points. Historically, it may have been inspired by similar Persian and Indian pieces. It is still worn by girls in Uzbekistan on their wedding day today.

Wood Carving

Wood carving is one of the most impressive forms of applied art found in Uzbekistan; considering the lack of modern technology, the sophistication of engravings from over 1,000 years ago is truly astonishing. Archeological evidence suggests the art of wood carving has been around since at least the 9th century. Carved items ranged from architectural columns, column feet, doors and khan-takhta (traditional tables) to smaller items such as pencil cases. Floral geometric patterns combine natural, Islamic and Zoroastrian elements. Elm, juniper, poplar, apricot and pane tree were some of the most common base woods, but they often had to be imported from hundreds of miles away in the case of desert cities like Khiva. The Juma Mosque in Khiva is a mini-museum of engraved columns, with 213 of them supporting the mosque’s roof. Some of these date as far back as the 11th century. In order to preserve the natural look of the wood, unrefined vegetable oil was often applied as a lacquer.

You’ll Also Love

Museums as Self-Care

In 2018, doctors in Montreal began prescribing visits to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) for patients experiencing depression, anxiety, and other health issues. This innovative approach to mental health treatment was launched under the initiative of the MMFA in collaboration with Médecins francophones du Canada (MFdC). The program allows physicians to provide patients […]

Guide to Bishkek’s Top Museums for Students

The Kyrgyz were largely a nomadic civilization up until the 20th century. The city of Bishkek has a number of museums documenting this fascinating history as well as the development of the arts and sciences in Kyrgyzstan. These museums were mostly established during (and today are often unchanged from) Soviet times, including a number of […]

The State Museum of Applied Art and Handicrafts History of Uzbekistan

The State Museum of Applied Art and Handicrafts History of Uzbekistan provides an excellent introduction to Uzbek history and culture. Centrally located in Tashkent, it displays more than 7,000 examples of traditional folk art. These include a range of mediums from decorative glass to porcelain and fabrics, all dating from the first half of the […]

Nukus Museum in Uzbekistan: Lysenko, Savitsky, and Preserving the Soviet Avant-Garde

In the remote Nukus Museum of Uzbekistan, a vast collection of banned Russian avant-garde art has been preserved for decades. The museum and its collection were founded by Igor Savitsky, a Soviet artist who defied censors to rescue and safeguard these works. His success was also made possible by the unique geography and history of […]

The Amir Timur Museum in Tashkent

The Amir Timur Museum, also known as The State Museum of Timurids History, stands proud at the center of Tashkent. Built in 1996 to mark the 660th anniversary of Amir Timur’s birth, the museum celebrates what it sees as a glorious history and places modern Uzbekistan as the direct descendant of that history. A visit […]