Russia only acquired Primorsky Krai, the region that contains Vladivostok, in the 19th century. China, the Mongol Empire and the Balhae and Jurchen nations had all controlled the area around Vladivostok before Russia gained it through the Treaty of Aigun with China in 1858.

Vladivostok was founded primarily as a Russian military post rather than a city. The civilian portions of the city grew around the military base, primarily to service, feed, and house the soldiers and sailors. Russia needed to heavily guard the territory, considering how far it was from Russia’s political center, and how close it was to China, Japan, and Korea, who were all known to be interested in newly-acquired Russian territory.

Russia had had aspirations to become a Pacific naval power since the 1700s, so the new territory, which would allow the realization of this desire, was a precious attainment to protect. The naval infrastructure built by the Tsar and, later, the Soviets, was also initially precious. However, much of it was quickly made obsolete by new technology or fell into disrepair due to a lack of funding. Much of it now lies in ruins, but all are still (officially or unofficially) able to be explored.

A Short History of Vladivostok’s Fortresses

The initial fortifications in the area, rather extensive for that time, were built through the 1870s-1890s. From 1878 to 1918 around 1,300 military objects – large and small – were built in and around the city. Vladivostok became particularly important after the fall of Port Arthur to the Japanese in 1905 during the Russo-Japanese War, since it was Russia’s only other Pacific seaport connected to the Trans-Siberian railroad. Ninety-eight billion rubles in gold were spent between 1910-1914 on the construction of defense infrastructure, including forts, strongholds, and access roads. Part of the reason the projects were so expensive was that each object had to be specially planned due to the hilly landscape. In more “designer-friendly” geographic conditions one design is used to construct multiple forts. To Vladivostok’s favor, however, the hills make the forts very difficult to spot, and the exact locations were kept secret.

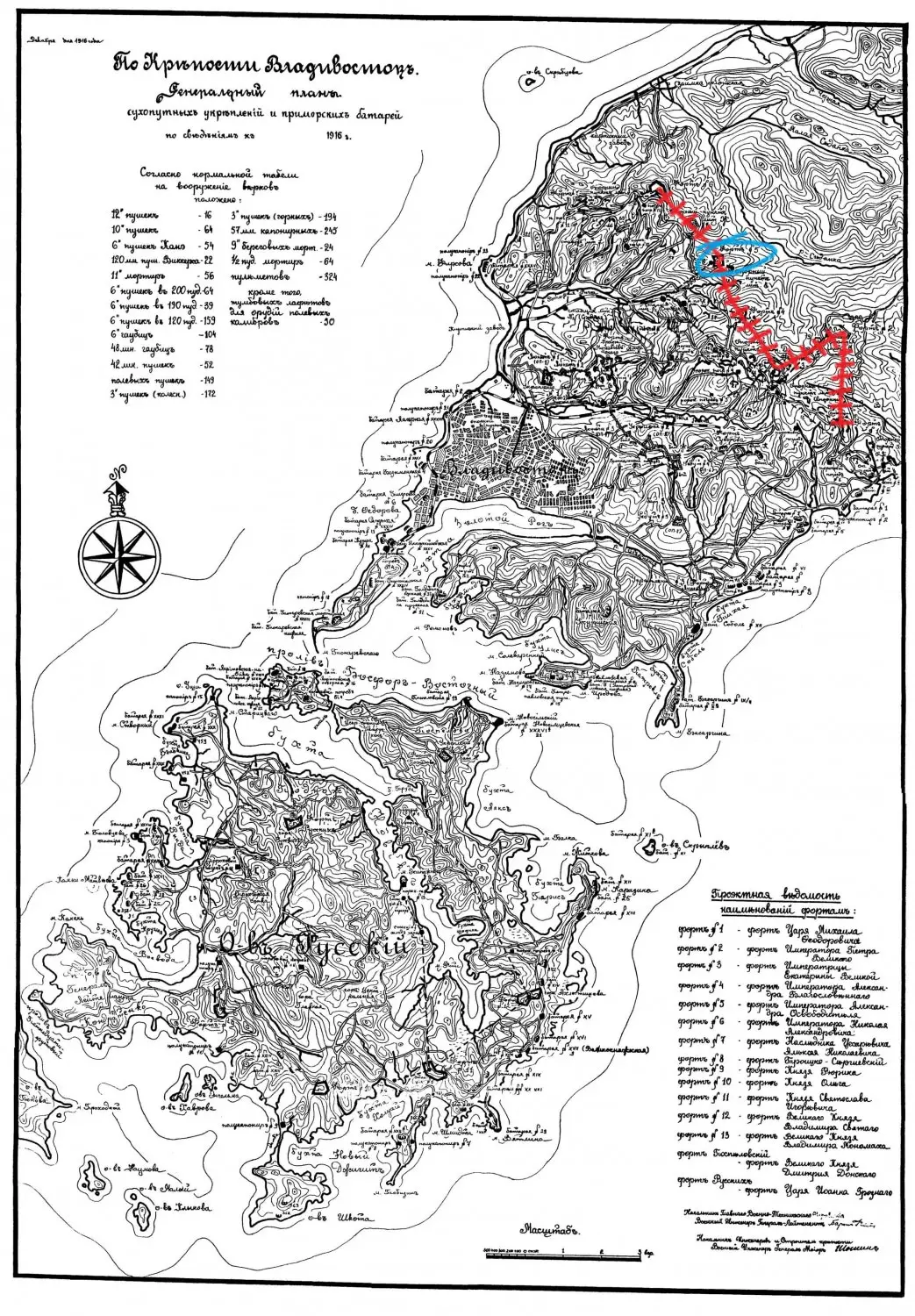

All together there are 16 forts that encircle Vladivostok from all sides, 10 of them on the peninsula, and 6 on Russian Island. Unfortunately, it seems that maps of the area are still scarcely available to the public – the only one we could find is this rather esoteric Russian-language, older map. Perhaps, as Russian Island is now being developed into a major tourist and business hub, a more complete and user-friendly map may be produced someday soon.

These naval forts were some of the last in the world to be constructed – permanent forts lost their use with changing military and war trends. Beginning in World War I, advancements in artillery and airpower meant that any detectable target could be destroyed, so the more resources spent on a particular object meant the more of a strategic target it became. Field (temporary) fortification became more relevant for increasingly technologically mobile troops. Thus Fort No. 2 is the largest fort of its type in the world and will likely remain so. It is 650 meters long and 380 meters deep, with more than 3.5 kilometers of underground tunnels.

All of the 16 forts encircling Vladivostok are intact except Fort No. 5, part of which was blown up in 2005 by when an illegal city ordinance called for the disposal of ammunition at the site. The Military Prosecutor’s Office claimed that senior officers of the Pacific Fleet did not know the fort was a federal monument and refused to initiate proceedings. Shortly after the explosions in Fort. No. 5 a survey group found undetonated explosives inside Fort No. 8 (though it is not clear who put them there).

Other forts have also been damaged by misuse. In a routine inspection of Russian cultural heritage sites in 2008 it was discovered that two-thirds of the metal in the gallery of Fort No. 2 was removed, making the passageways of this fort unsafe (it is also an unsolved mystery as to what happened to the metal). Other military objects in and around Vladivostok have been targeted by illegal scrap-metal looting as well, and after a series of incidents most of the forts now have the reputation of being a dumping ground for bodies and stolen goods (passports, wallets, etc.). Nobody besides the Vladivostok Digger Club, an amateur archaeological club, seems to care very much about the forts. Most of the forts are in a poor state after a century of fighting with nature and human neglect.

Lisa Horner

Vladivostok Fortress Museum

Scattered across Vladivostok’s coastal slopes in quite a few places one can see the metal and concrete remains of the old coastal batteries built to defend the city in years past. Most of the emplacements are just curios–disused relics that add a little extra spice to an already flavorful city. But near the old city center, one of the old batteries has been turned into a museum filled with some of the fascinating military history of the Far East region.

The Vladivostok Fortress Museum is conveniently located Batareynaya Ulitsa by the waterfront, about a five minute walk from the football stadium. The cost for entry is 600 Rubles.

The first things you see walking up the stairs to the museum are two large guns stationed behind a thick wall of concrete. Although trees now somewhat obscure the view, it’s easy to see how these guns used to have a commanding field of fire across the Amur Bay. Next, the museum itself has been built inside the old casemate. The museum’s contents span from armor and weapons used at the time of the Mongols, to letters and documents from the area’s early Russian history, all the way to the final Soviet modernization of the city defenses in the late 1960s. The museum really does have a lot of pieces on display. Dioramas and maps give good insight into how the city and area have changed and it’s actually surprising how many pistols, rifles, machine guns, and anti-tank weapons they managed to fit into such a small space. It actually makes the space feel slightly cluttered.

The space around the museum casemate is also filled with old weapons and vehicles. Torpedoes, rockets, flak guns, anti-tank guns, more coastal defense guns, and armored cars are all open to inspection. Finally, you can even climb up to the roof of the encasement to get a better view of the bay.

Construction of Vladivostok’s coastal defense system began in 1862, when several wooden emplacements were built to house smoothbore guns. It wasn’t until 1899 that the defenses were upgraded to more resilient concrete emplacements. They have been put to the test only one time, in 1904, when the Japanese bombarded Vladivostok during the Russo-Japanese War. Although it was a relatively minor engagement, it did reveal some weaknesses in the city’s bulwark, and so the defense system was redesigned. Prior to the beginning of World War I, gun emplacements were built further out from the city defending the mouth of Ussuri Bay where the impressive Russian Island Bridge now stands. Throughout the Soviet period, the emplacements around Vladivostok were maintained and sometimes upgraded. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the defenses fell out of use altogether until the location that I visited was turned into a museum in 1996.

Jonathan Rainey

Fort No. 7: Partially Renovated

Today most of the old forts are not easy to visit on your own. Most of them have been completely abandoned. Years of neglect have made them a bit dangerous to walk around in and destroyed any roads that may have lead directly to them.

The most commonly visited abandoned fort, Fort No. 7, is only accessible by a dirt road and there are no signs to point the way. Entrance is technically supposed to be open for all, but the man who currently lives there keeps the place entirely locked up and only unbolts his window when somebody knocks on it. If you really want to get inside, your best bet is to arrange it through a tour agency that has the gatekeeper’s phone number – if you are lucky they will call him ahead of time. If he is in a good mood he might even remove the chain blocking the dirt road to the fort ahead of time. Otherwise you will have to walk.

After discussing our intents with my tour guide and having decided we were harmless, the gatekeeper, Grisha, walked around to the front and unbolted the main fort entrance for me and the guide. Grisha led us by flashlight to the room that serves as the main headquarters. There is no natural light in the corridor – when the fort was in use lanterns were placed in sills built into the walls.

The room we entered, originally the kitchen, contained a gas-stove and a table spread with a sorry assortment of souvenirs such as a few magnets, a picture book of Vladivostok’s various forts, and military rations. The room also contained a map of the fort, a couch where Grisha sleeps, a computer with an old Soviet film on pause (probably interrupted when my tour guide knocked on the window), and various rusting pieces of indistinguishable equipment spread among Grisha’s own personal things.

Grisha lives on the premises and when there are no tourists he studies his real main interest – ufology (the study of UFOs). If you’re alone or with a small group he might tell you about his interest in ufology. He has hundreds of pages of notes. Otherwise he will skip directly to an introduction of the fort.

Officially named “The Fort of the Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich,” it was built in 1910 into the side of Mount Toropov, 14 km north of the center of Vladivostok. It’s the western-most fort on the northern defense line, and was designed by an experienced military architect, Vyacheslav Sergeyevich Toropov. Fort 7 has the longest barracks of all 16 forts – 150 meters, with the capacity to house 400 soldiers. During wartime it was filled to capacity, and in peacetime only a handful of soldiers were stationed there. The barracks’ deep foundation was even equipped with a full kitchen, oven, and even its own power station. The water supply came from an artesian well inside the fort, and the artillery room was equipped with a forced ventilation system so that the gasses from the artillery would not poison the soldiers.

Construction of the sprawling fort was never completed due to the October Revolution in 1917, but what was left was minor – for example, not all the equipment was installed, and the countermine galleries were not completely finished. During the Russian Civil War the fort and remaining construction equipment were kept under guard by the Whites until 1923, after the Bolsheviks had taken control and signed a treaty with Japan regarding the demilitarization of Vladivostok. The fort was abandoned and later looted by unknown bandits. It’s rumored that from the 1930s until 1940 the forts were used by the NKVD (secret police – later known as the KGB) as an underground execution area.

The fort never saw any actual fighting. It was used as a storage facility in WWII, housing mostly weapons. It was also officially used as a storage facility from 1962-1996, but its still a mystery as to what, exactly, was kept there. Locals report covered military trucks transporting cargo to and from the site, but can’t say what kind of cargo might have been inside. After Perestroika and the reduction of the military and navy, Fort No. 7 was abandoned and again plundered by unknown criminals. It was only made presentable and opened to the public for tours in 2001, when former officer Sergei Popov took an interest in restoring it.

The main attraction of the fort are the underground tunnels, which have a total length of 1.5 km and connect the fort’s entire defense system, intersecting and then taking off in different directions. It was designed so that riflemen and artillerymen could move quietly from one end of the fort to another, and appear in places the enemy would not expect.

The concrete tunnels are completely dark inside – electric lighting was installed during restoration, but it rarely works. Temperatures inside the fort range from 50-57 degrees Fahrenheit during summer, and in winter the temperature inside the fort is usually the same as the temperature outside, never rising above 40F. There are enormous icicles that form inside during winter as the concrete has since cracked and begun leaking.

The interior of the tunnels is basically cleared out, with only a few odds and ends left – some ammunition, a few cots in the barracks, etc. A skate-boarding youth group is allowed to come in on some weeknights to skate.

There have been several scandals associated with the fort during the last 10 years. In the early 2000s its rear line of defense was demolished so that a few upper-class vacation homes (dachas) could be built there. In July 2007 there was a local scandal when representatives of the Thai Boxing Federation of the Primorsky Region showed up – armed – and claimed the fort was theirs. The Federal Agency for Managing Historical and Cultural Monuments had officially leased the fort to the Thai Boxing Federation. Sergei Popov, who had been taking care of the premises and conducting tours there for years, did not have the formal rights, and was forced out to the chagrin of the local population and media. The scandal was largely tied to the fact that a bus full of school children was visiting the fort when the armed Thai Boxing Federation showed up to claim the fort, but there was also a good deal of sympathy toward Popov.

landscape as camouflage and protection.

The Federal Agency for Managing Historical and Cultural Monuments claimed that Popov, who had reopened the fort to the public and renovated it for tours, had done so illegally and had been resisting formalizing his operation of it. Thus the federal agency began looking for other tenants and signed a lease with the Thai Boxing Federation so that the funds made from the rent could be used for the fort’s upkeep. The Thai Boxing Federation wanted the premises mainly as a training base, but also promised in the lease that the excursions of the fort would continue.

Popov, on the other hand, claimed that he had been seeking to formalize his management of the fort for years, but had been categorically ignored until he began making money on the excursions. The fort was only temporarily closed during the confusion of who was the legal tenant before reopening to the public – by the Thai Boxing Federation.

The last scandal associated with Fort No. 7 was that the Thai Boxing Federation illegally installed a fireplace in 2008, and had to pay a fine for neglecting their responsibility to keep the object of cultural heritage unaltered.

No matter who the owner is, the fort is likely to remain open to tourists for a long time, considering its cultural and historical importance, that it draws tourists to the area (many from Asia), and that it is the only of Vladivostok’s forts suitable for excursions. Whether the operation becomes more formalized with easier access, so tourists don’t have to trail behind their tour guides knocking on windows to be let in – is much less clear. However, it’s still the type of adventure that any adventurer heading to Vladivostok in Russia’s Far, Far East should relish in.

Lisa Horner

Fort No. 5: Ruins

No security or facilities – enter at own risk

Vladivostok has a ring of hills to the north which acts as a natural wall for the peninsula. But what nature has made, man has improved. During the early 20th century, when threat of Japanese invasion was a real concern, the Tsarist and later Soviet governments put considerable time and money toward ensuring a strong defense for the city. Each of the main northern hilltops houses a fort with a commanding view of its surrounds.

These forts were not the kind with towers and broad walls though. These were modern forts, built into the hills rather than on top of them. Deep tunnels provided safety from the bombs and artillery, and the only things visible from the outside were a few squat, concrete structures.

Today, a few of Vladivostok’s forts have been turned into museums, but the rest have been abandoned completely. Abandoned forts make for great exploration, so I jumped at the chance when one of my hiking buddies here asked if I wanted to come along on a weekend excursion. From the bus stop, it took about an hour and a half of hiking to reach the hilltop. After we had a bite of lunch, we switched on our flashlights and descended into the fort’s dark tunnels. Although Fort Number 5 is a fairly popular hiking destination, there is nothing in the way of safety precautions inside. A good flashlight is a must and not the kind that comes on a cell phone. Broken pieces of concrete, sharp debris, broken stairs, patches of ice, and even random 15-foot-deep holes in the ground are all common in the tunnels. Although I don’t think that they are extensive enough to get truly lost, having a friend who knows something of the layout is certainly helpful.

Image slightly modified from wikimedia.org

We spent another hour and a half or so underground and explored most of the nooks and passages. Unfortunately, my photos of the interior did not turn out very well, but it has the general ambiance of a horror movie, which is another very good reason to go with a friend. After emerging from the deep, we were greeted with splendid views of the northern countryside and the Amur Bay already beginning its long winter freeze.

Our full trip took 6-8 hours. It’s the perfect length of time for a weekend excursion to see one of Vladivostok’s more unique sights, and still have time to hit the city center once it gets dark.

How to get there: Reaching Fort No. 5 is actually fairly simple. From the Гоголя bus stop, just hop on board bus number 40 until the end of the line at Завод Варяг. After departing the bus, walk to the right on a short road between the apartment buildings. This turns into a dirt path heading into the forest. Keep to the right on this path, which will begin to loop around the construction site (at the time of writing) for a new hospital. The destination will be the Де Фриз- Патрокл- О. Русский, which is one of the main highways linking Vladivostok with the rest of Primorsky Krai. The only way to cross this highway is via the overpass, which conveniently happens to be the road leading to Fort No. 5. Follow this road up the hill for approximately 1 mile and look for a smaller trail on the left which goes to the fort. I’ve marked the route, from the bus stop to the fort, on Google Maps for convenience.

Jonathan Rainey

Abandoned Underground Tunnels

No security or facilities – enter at own risk

Vladivostok is not unique in being home to a large number of abandoned structures (заброшенные структуры) with deep and often unique historical roots. When the Soviet Union fell, many buildings and projects became unneeded or lost funding and were then sold or simply left to their own devices. The result was often ruinous for the artifacts involved. However several of these structures in and around Vladivostok remain accessible to the public. The Vladivostok Digger’s Club (Владивостокский диггер-клуб) is a privately run and funded organization that conducts tours of these various historical attractions. Along with a group of Russian students studying at our university, we organized an excursion into a system of subterranean passageways of which many locals are utterly unaware.

Meeting in the very heart of the city in winter attire despite the uncharacteristically warm evening in mid-March, it was hard to imagine that we were about to step into the year-round damp, cold air of an underground passageway once roamed by members of the NKVD (Народный комисарият внытренних дел), the precursor of the KGB and the current FSB. More than just a hideaway for the Soviet secret police, the primary function of this 1.5km system of tunnels constructed between 1939 and 1942 was to provide a safe haven in the event of an attack on the city. After all, as the world was gripped by the events at Pearl Harbor during this period, the Soviet Union’s Far Eastern port paid especially close attention, recognizing its proximity to Japan and comparatively far inferior naval power. Indeed, this system of tunnels was even purported to be nuclear-ready and sported an escape tunnel (no longer accessible) with a below water exit hatch to allow evacuees of exceptional importance an escape route to the Pacific without ever having to break the water’s surface!

While the tunnels are still comfortably accessible, after several decades of misuse and neglect, it is hard to imagine any living thing would choose to take shelter there. The air is cold, damp, and heavy. While the integrity of the craftsmanship, with the exception of the deepest laid tunnels with depths of more than 70 meters below ground level, seems to have stood the test of time, the grey cement interiors are anything but cheery. Any exposed metal has become heavily rusted in the damp environment and leaks and cracks cause enormous icicles in winter and tickling inflows of water in the spring. In short, as our guide warned us before our entrance, the interior is anything but glamorous.

It was quite obvious in the three hours our guide walked us through the passageways that the history he told us was likely only a fraction of what he knew. Even for those not entirely taken by the history of the tunnels, there seemed to exist a universal intrigue simply in having the chance to be in such an unusual environment. This feeling for me peaked when, at the last stop on the tour, 72 meters below the earth’s surface, everyone turned out the flashlight they had been provided and stood in total silence for two minutes. While some were obviously ready for the end of those two minutes, I would have preferred their prolongation. The sensation of utter nothingness with regard to light and sound was powerfully total.

While in my opinion, two hours would have been more than enough for the expedition, history buffs would probably feel robbed by the measly 3+ we spent inside. Though I must say, our guide did a good job of making the tour both entertaining and informative.

For further information on what the Digger’s Club does and the events they host, click here. For more information about the history of Vlad’s forts and abandoned structures, click here. Of course, for the most telling insights, get out there and check them out yourself!

Alex Misbach