The Peredvizhniki, or the Wanderers, were a movement of Russian Realism born from the Imperial Academy of Arts in 1863. Under the rule of Alexander II, Russia was struggling through a series of liberal reforms that were part of a greater humanitarian movement. The emancipation of the serfs in 1861 deconstructed much of the social and economic hierarchies that had defined tsarist Russia for centuries. Paralleling these social and political movements, progressive thinking took hold of the artistic world as well. Further, the Wanderers would also follow and pioneer new ways of thinking about art genres and new ways in which art was sponsored, displayed, and purchased.

Historical Background of The Wanderers

Founded under Catherine the Great in 1764, The Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg fostered a conservative attitude that promoted neo-classical style, biblical and mythological subject matter, and the stringent divide between high and low art. Teachers fiercely adhered to the neoclassical style and taught students to value tradition over innovation.

A century later, however, Russian society was changing with new technology, social forms, and ideologies. While the reforms invoked by Tsar Alexander II promoted an idea of increased equality, in actuality immense poverty and social inequality remained. Serfs were freed from the bondage of service, yet had to struggle with few resources to develop a successful livelihood. Some left the countryside to seek work in the cities, but there also encountered long hours, hard work, and often dehumanizing conditions.

Following the French Revolution of 1789, anti-monarchist republican ideals spread eastwards to the Russian Empire. The political philosophy of German materialists resonated with the intelligentsia and the disillusioned public alike.

These ideals first surfaced in Russia in literature. In 1852, famed author Ivan Turgenev (1818-83) released the highly influential anthology Sketches from a Hunter’s Album. This collection depicts the lives of common Russian people, delving into the everyday struggles of people such as doctors, farmers, and overburdened wives. Humanizing the lower classes while exposing the unjust behaviors of many members of the upper echelon, Turgenev’s work was an early example of the wave of Realist literature and art that would characterize the remainder of the 19th century. Reflecting the suffocating censorship enforced under Tsar Nicholas I, Turgenev published Sketches from a Hunter’s Album while under house-arrest from having publicly supported the subversive author Nikolai Gogol (1809-52). Tsar Nicholas I also kept a watchful eye over the Imperial Academy, heavily involving himself in the process of appointing committee members and forcibly “retiring” artists whose work he found unsatisfactory.

After the death of Nicholas I (r. 1825-1855) placed Alexander II (r. 1855-1881) on the throne, the administration ushered in a series of reforms aimed at alleviating social distress and boosting Russia’s sluggish economy. In 1858 censorship became less severe, allowing criticism of the establishment to circulate more openly. Soon paired with the Emancipation Reform of 1861, which created a new class of freshly liberated former serfs, this reform invigorated not just the urban centers but also the countryside with a revolutionary spirit. An era of freethinking began in Russia. Unfortunately for the state, much of this new thinking was anti-capitalist, anti-state, and anti-bourgeois, populists rejected traditional values in all facets of life, including the arts. Populism flourished, characterized by the widely influential works of Mikhail Bakunin (1814-1876), Nikolai Chernyshevskii (1828-1889), Dimitrii Pisarev (1840-1868), and other radical thinkers.

As liberal ideas spread across the upper echelon, many students of the Imperial Academy began to question the conservative restrictions of the monarchist institution. Further, the styles propagated by the academy’s teachings were in conflict with Realism, the art style that many modern painters saw as the best tool for portraying how they saw the world and believed that the world should be portrayed, in accordance with the increasingly materialist philosophy being adopted by many commoners and intellectuals alike.

The topic of the Academy’s annual Gold Medal painting competition in 1863 was announced as “The Entrance of Odin into Valhalla.” Many students found the competition’s subject not only outdated and irrelevant, but also removed from the realities of Russia and her people. In dissent, 14 students left the Academy to form an independent Artists’ Cooperative Society, also sometimes called the Artel of Artists.

From Artists’ Cooperative Society to The Wanderers

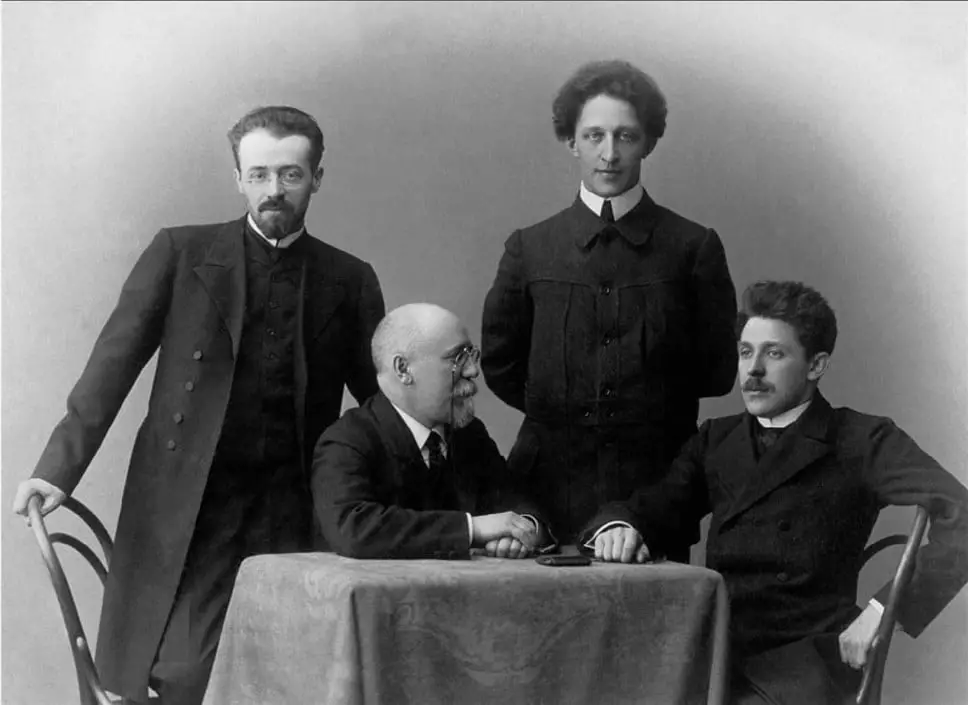

Led by Ivan Kramskoi (1860-1880), the fourteen students created a de facto commune. They shared studio and living space and also pooled a percentage of their earnings for group advertisements. Most of these artists were otherwise employed, working as icon painters, photographers, and assistants while their truly creative artmaking was now relegated to a passion-project.

Each artist had his own preferences in both style and theme, but the Artel’s unifying characteristics were depictions of Russian landscapes, portrayals of the peasant class, and the use of naturalistic representation. Leaving behind the Academy’s notion that fine art should depict neoclassical or romantic subjects, these artists sought to harness art as a means of creating social change.

As an activist group as well as a community of artists, the Artel emphasized the importance of self-improvement through reading and discussion, creating weekly forums to debate popular civic and social issues of the day. They also showed their works privately in their own studios, allowing them to create and display works at minimal cost.

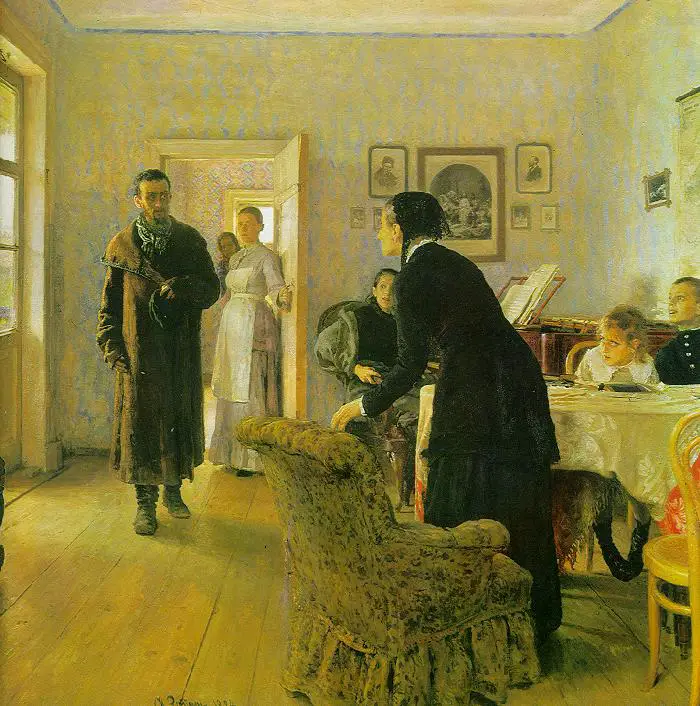

Although the Artel was short-lived, dissolving in 1871 after a dispute caused by one member negotiating with the Imperial Academy, Kramskoi and three other members of the Artel would soon form the Society for Itinerant Art Exhibitions. Members of this group became known as the Peredvizhniki, commonly translated as either the Itinerants or the Wanderers. Grigoriy Myasoyedov (1834-1911) is credited with organizing the Society for Traveling Art Exhibitions, and soon their numbers grew as the group accepted both firmly established and freshly debuting artists.

The Wanderers: From Outcasts to Mainstream

The goal of the Society for Traveling Art Exhibitions was two-fold: to make art accessible while promoting a greater understanding of the media, and to depict the diversity and daily realities of the Russian population, regardless of social and economic class. Rather than focusing their artistic attention on the aristocracy and inaccessible images of Greek mythology, the Society depicted a profoundly humanistic view of the true Russian life, in all its beauty and hardship.

By November of 1871, the Wanderers opened their first exhibition. It was held in Moscow at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. The Moscow School, though considered less prestigious than the Imperial Academy, was a far more progressive institute. Accepting of experimental practices and changing attitudes both in the arts and in political philosophy, the college’s willingness to adapt, and to hire professors who worked in new modes, gave the college a prominent role in maturing Russian Realism.

Vasily Grigoryevich Perov (1833-82), the eldest of the group at 37 years old, accepted a position teaching at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture in 1871. In the following decade, the connection between the Wanderers and the Moscow School would grow stronger. Vasily Polenov (1844-1927), Vladimir Makovsky (1846-1920), and Illarion Pryanishnikov (1840-1894) all became associated with the Wanderers and all eventually taught at the Moscow School.

As their success grew, they were able to bring their exhibitions across the nation and its provinces, reaching the cities of Kiev, Kharkov, Nizhnii Novgorod, Kazan’, Samara, Penza, Tambov, Kozlov, Voronezh, Novocherkassk, Rostov, Taganrog, Ekaterinoslav, and Kursk. During their over five-decade history, the artists arranged 48 exhibitions and brought their progressive art and ideals to millions of Russians.

Along the way, the group attracted the attention of influential figures, including Vladimir Vasilevich Stasov (1824-1906). A renowned critic, Stasov’s formal approval gave legitimacy to the group.

Through the 1880s and 1890s, the Wanderers gradually shifted ideologically. The association went from a counter-cultural group working contrarily to the dominant style to becoming the dominant style.

The Wanderers’ Revolution in Landscapes

Although landscape paintings seem to have an almost universal appeal, retaining popularity across time and culture, this had not been the case for Russian landscapes before the Wanderers. Under the Imperial Academy, artists were told that the ideal natural environment suitable to be represented in oil could not be found in the Russian countryside, so the majority of landscapes produced by Russian artists were of Western European locations, often modeled after Switzerland or Italy.

The Wanderers disagreed with this, feeling that Russia’s unique landscape, like its peasants and culture, were absolutely worthy of artistic representation. This was also central to their goal of showing the Russian population subjects and locations which resonated with them. The Wanders also painted the landscapes as they were, rather than trying to idealize them. While anyone could appreciate the beauty of the Mediterranean Sea glimmering at sunset, they argued, only a true Russian could appreciate the austerity of a snowy birch forest or a frozen Siberian bog. Thus, the marketability of the landscape in late 19th century Russia is connected to the idea of national identity.

Many of Alexei Savrasov’s (1830-97) dealt with spring, a season typically known in Russia as one dominated by mud. However, he claimed to find great beauty in the first signs of life after the long Russian winter and had great early success with his 1871 work, The Rooks Have Returned, where Savrasov’s subject is a village, with one home occupying the middle-ground as a line of receding cabins leads the viewer’s eye to the horizon, where the spires of a distant church can be discerned. In the foreground a frozen pond and two spindly birch trees rise out of the otherwise barren snow. A few rooks peck at the ice while others take to the cloudy sky. Savrasov’s placement of the birds on the canvas helps to create a sense of balance, as the birds reflect the lean of the birch tree on the opposite side of the composition.

He returned to the subject often. For example, in Early Spring, Savrasov works with a limited color palette. The majority of the canvas is gray or white, with a cool, dark brown being the next-most prominent. Yet, the gray of the sky and white of the snow have a tinge of warmth. A hint of ochre pervades the scene, creating the impression that the scene occurs in the evening, as the sun, though hidden in the clouds, casts a soft hue over all below. As well as the sight tint of ochre, Savrasov adds delicate touches of blue, most obvious in the frozen pond. The ochre and blue complement one another, creating visual interest in Savrasov’s subdued palette.

Through a simple, yet balanced, composition, and a limited, yet effective, color scheme, Savrasov’s Early Spring is an appealing work that teeters on the edge of austere. His audience of Russians can easily enjoy this piece, while feeling more connected to the subject matter all the more because its beauty is not ostentatious. Although the scene may read as an average winter’s night to many viewers, his intended audience will recognise the presence of the rooks and the slight thawing of the pond as signs of early spring; a universally joyous sight for those in Russia.

Many other members and associates of The Wanderers are also particularly known for their landscapes that bring to light the subtle magnificence of nature in Russia. While foreign viewers might have little appreciation for such a harsh and sometimes bleak countryside, the Russians were reminded of the particular magnificence of their land and their connection to it. Russians have a unique connection to their homeland – one forged in the cruelest of seasons, through the cultivation of the earth. By consequence, from fairytales to ancient religion, the landscape has long held an important place within the Russian mind. Artists Ivan Shishkin, Alexey Savrasov, Vasiliy Pelenov and Isaak Levitan, among others, were noted for their work as landscape artists during the movement.

Further, landscape painting had the advantage of broad appeal, even in the highly divisive political environment of the final years of Tsardom. Finding identity in the land itself was a way of avoiding searching for identity in the crumbling forms of past Russian identity, which had been intertwined with Orthodoxy and the Tsar for centuries. Now that these polygons of identity were under question, Russians found a sense of self, of national unity, and of stability in the physical land that they lived, worked, and died on. Love of country became love of the land, so despite hatred towards the unjust establishment citizens could still find national pride.

The Wanderers’ Social Protests

This is not to say that the Wanderers’ did not also directly address corruption in society, including religious corruption. Many of their pieces were filled with populist themes that celebrated the beauty and honesty of the peasantry while simultaneously protesting social issues and faults in authoritative figures.

Vasily Perov (1834-1882), for instance, openly depicted themes of social and religious realism in his painting Easter Procession (1861). The painting shows drunken clergymen exiting the local tavern amidst a crowd of both religiously devout and apathetic peasants. His composition shows the church leaders as fraudulent and the peasants as more devoted and holding greater integrity than their religious leaders.

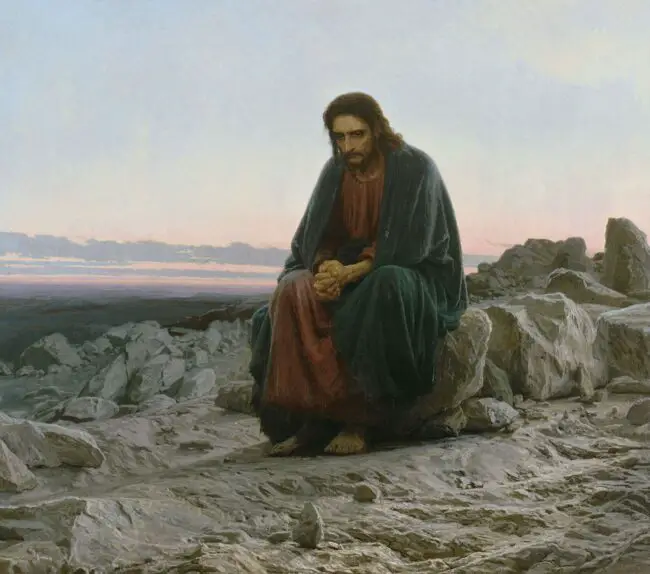

Other members of the Wanderers created relatable images of Christ as a very human man removed from inaccessible neo-classical Biblical imagery. Ivan Kramskoi (1837-1887) is noted for his piece Christ in the Desert (1872). The painting portrays Christ after his forty days and nights spent wandering and fasting in the desert looking as haggard and exhausted as one would expect for a man who has just been through such an ordeal. His internal and external pains are clearly visible. Such a piece strongly contrasts the neoclassical standard of 19th century Russian art as seen in Alexander Ivanov’s (1806-1858) painting The Appearance of Christ to Mary Magdalene (1836) in which Christ is a milky-white body-builder in a toga. Ivanov’s Christ doesn’t visibly bear the burden of humanity’s salvation. He is not God incarnate, but rather God himself. Kramskoi gives a polar opposite portrayal less than a half century later.

These social and religious pieces often came under criticism for their openly liberal themes and controversial ideals. Yet, as a part of a larger artistic movement involving the literary world, the Wanderers were increasingly encouraged to act as social commentators and catalysts for change. Writer, revolutionary and socialist, Nikolai Chernyshevsky, greatly influenced the developing democratic movement that inspired the progressive steps of the Wanderers and their literary brothers. As author of the novel What Is to Be Done?, Chernyshevsky was an early critic of current political and social structures and demanded that social and moral commentary be an essential function of the arts. Under such responsibility, prominent artists of the movement such as Vasily Perov, Ivan Kramskoi, and Ilia Repin depicted societal truths in their work, as did writers of the age including Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy. Despite criticism towards their ideology and aesthetic, these artists believed their work to be much more than simple portrayals of the people. Rather, they believed it to provide a crucial social service.

The Wanderers in Russia’s Changing Art Market

Importantly, the Wanderers were not radicals. Although they were a largely philanthropic group, working to advance artistic, social, and ideological ideals, many of these artists were likely as motivated by social advancement as by altruism. Artists of this age, largely belonging to the lower-middle class, or the “petty bourgeoisie,” were faced with the choice to either appeal to the dwindling conservative court or cater to the emerging leftist intelligentsia. As the educated class continued to gravitate towards the egalitarian ideals of Marx and other Western thinkers, the choice to divorce oneself from the academy to better align, and hopefully assimilate, with the modern intelligentsia became a progressively easier decision. Elizabeth Valkenier (1926-), a specialist of 19th century Russian art, argues that these young artists were more occupied with striving for freedom in their own personal and professional lives than with liberating the lower classes. And although the subject of their art was so often the overworked farmer or the fatigued factory worker, the farmer and the worker were generally not their audience. The art of the Wanderers was not accessible to the masses, but instead was intended only for the cultural elite.

Displaying not only in these large cities but also in smaller towns along the way, the Wanderers accessed a new demographic, bypassing the system of aristocratic patronage demanded by the Academy. Not only could the artists communicate directly with buyers, rather than relying on the Academy as a middle-man, but they could charge substantial entrance admission. Those that attended and especially those that purchased the paintings, however, tended to be from moneyed classes.

One of the most influential patrons of the group was Pavel Tretyakov (1832-98), who had amassed a sizable fortune in textiles and banking. Tretyakov, known to buy whole series from artists, owned the largest collections of Perov, Kromskoi, and Ilya Repin (1844-1930) anywhere. Among others, he commissioned these three to paint a treasury of portraits, in the goal of creating a comprehensive portrait gallery of Russia’s most influential figures. Tretyakov secured the legacy of the Wanderers by opening the Pavel and Sergei Tretyakov City Art Gallery in 1893. This museum eventually became the Tretyakov Art Gallery and is still well known for its collection of portraits.

Finally, the ability of the Wanderers to survive as a group, and their ability to form a lasting legacy can also be partially attributed to the growing postcard industry. The newly developed idea of the postcard, only patented in the early 1860s, lent itself well to the scenic landscapes of Savrasov, Ivan Shishkin (1832-98), and Issac Levitan (1860-1900). This affordable means of mass communication allowed works of the Wanderers to travel even beyond the scope of their exhibitions and keeping their works relevant in popular culture for decades. Postcard printing, however, was also the domain of moneyed business men who typically had the printing done in England and postcards then imported in bulk to Russia.

The Critical Legacy of the Wanderers

By the 1890s, as the Wanderers’ style and methods became mainstream, many members, including Repin and Makovsky, formed connections with the once antagonized Imperial Academy. They accepted positions in the faculty and administration and aligned themselves with Tsar Alexander III (r. 1881-94), placing the group under the influence of the monarchy that it had once worked so hard to disavow.

At the same time, it can be argued that from this prominent platform, the Wanderers were able to spread their progressive message on an even greater scale. They taught Russia’s up-and-coming artists to understand their work as more than simple aesthetics, but rather as an opportunity to discover the soul of humanity and to work to improve the lives of the common people and society at large. The ideals they set out, especially early on, helped to eventually create the revolution that overthrew the Tsar, for better or worse.

In any case, as the members aged from passionate 20-somethings to more conservative middle aged men, young, creative artists gradually cut ties with the group, and the Wanderers stagnated. Despite the end of their golden age, the Wanderers continued creating and exhibiting for decades to come. Weathering the 1905 Revolution and the 1917 Revolution, their final exhibition did not take place until 1922.

The Wanderers succeeded in reshaping individual and institutional understandings of art. Even so, their movement began denying new styles of art the very artistic freedoms they had initially fought for. As the nation underwent political revolution at the beginning of the 20th century, movements of Russian modernism and the avant-garde gained momentum. Rather than fostering a continued appreciation of originality and innovation, the Wanderers lost themselves in resistance to change. Yet despite disintegration, the achievements of the Wanderers forever redefined what it meant to be Russian – in art, identity and nationality.

You’ll Also Love

How Art Nouveau Became an Expression of Latvian Identity

Latvia’s rich Art Nouveau heritage was shaped by European trends, influenced by local folk aesthetics, and popularized under Latvia’s National Awakening, a movement that first sought to define what it meant to be proudly Latvian. Art Nouveau flourished in Latvia for less than two decades. It rose with the economic prosperity and social mobility at […]

How to Start Studying Russian and Soviet Art and Architecture

“If a student came to you and said that they were interested in Russian or Soviet art but were unsure where to start exploring it further, what books and authors would you recommend?” This question was asked by SRAS Intern Taryn Jones of Elena Varshavskaya, who for many years taught art history at the Rhode […]

The Wanderers: An Early Revolution in Russian Art

The Peredvizhniki, or the Wanderers, were a movement of Russian Realism born from the Imperial Academy of Arts in 1863. Under the rule of Alexander II, Russia was struggling through a series of liberal reforms that were part of a greater humanitarian movement. The emancipation of the serfs in 1861 deconstructed much of the social […]

The Leningrad School: Preserving Tradition and Testing Boundaries in Soviet Painting

The Leningrad School was a prominent school of painting during the majority of the Soviet period, 1930-1990. Emanating from the Ilia Repin Institute for Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture (named for the famous nineteenth century realist painter and renamed the St. Petersburg Institute for Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture after the collapse of the USSR), it produced […]

What Was Russian Symbolism?

Russian Symbolism, a diverse literary and intellectual movement at the turn of the 20th century, played a pivotal role in Russia’s adoption of Modernist culture. Inspired in part by the French and Belgian movements of the same name, Russian Symbolism was also a response to the academic moralism and stiff utilitarianism that dominated Russian artistic […]