The Amir Timur Museum, also known as The State Museum of Timurids History, stands proud at the center of Tashkent. Built in 1996 to mark the 660th anniversary of Amir Timur’s birth, the museum celebrates what it sees as a glorious history and places modern Uzbekistan as the direct descendant of that history.

A visit to the Amir Timur Museum is a gateway to understanding Uzbekistan’s history and modern identity. That said, the museum was created as a nation-building enterprise, and the full history is much more complex than even this large and fascinating museum tells.

Who Was Amir Timur?

Timur was born in 1336 in Kesh, a city now known as Shahrisabz in what is now Uzbekistan. Although the museum does not directly point this out, Uzbekistan at that time did not exist. Amir Timur spoke Chagatai, an ancestor of modern Uzbek, as his mother tongue. The Chagatai were of Mongol descent but had been Turkified in many aspects, including their language. Timur saw his heritage as strongly Mongol, tied most to a lineage shared with Ghengis Khan and (perhaps imagined) ties to great heroes of Persia.

Thus, Timur was a Turco-Mongol conqueror who founded the Timurid Empire and set Samarkand as its capital. Today, he is regarded as a great military leader who unified the Central Asian territory. He is remembered as a patron of art and science and the founder of the Timurid Renaissance. His alternate name, Tamerlane, comes from the title used by his Persian enemies. In his twenties, he was injured by arrows while stealing sheep. He lost two fingers on his right hand and much of the use of his right leg, which left him with a pronounced limp. His Persian-speaking enemies would refer to him as Timur-i lang (“Timur the Lame”), which became corrupted to “Tamerlane” in Europe. However, his handicap did not prevent him from either leading his armies or personally fighting in battles. He simply trained himself to work around his handicaps. Because “Tamerlane” is derived from a pejorative, Amir Timur or simply Timur are much more culturally appropriate names for him.

Amongst Timur’s notable descendants are Mirzo Ulugh Beg, a respected ruler and scholar, Huseyn Bakkara, the governor of Khurasan, and Zahriddin Muhammed Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty in India.

The History and Rhetoric of the Amir Timur Museum

The Amir Timur Museum opened on October 18th, 1996. Its collection contains more than 5,000 artifacts dedicated to the life of Amir Timur and his descendants.

The building of the Amir Timur Museum followed the larger trend of Karimov’s effort to form a national identity around a glorified national history. Thus, Karimov built the museum to honor Timur. This trend can be observed in the vibrant teal dome that tops the museum, which recalls the Gur-e Amir in Samarkand, the final resting place of Timur. Additionally, in 2001, shortly after the museum’s construction, its image was placed on the 1000 som banknote. This act illustrated the museum’s national symbol as it helped promote and celebrate the new building. Furthermore, the nearest subway station to the museum is named after Timur and signs along the station’s walls give directions to the museum, encouraging riders to visit. Exiting the subway, one must walk by the Amir Timur Square with a central statue of him posed on a horse.

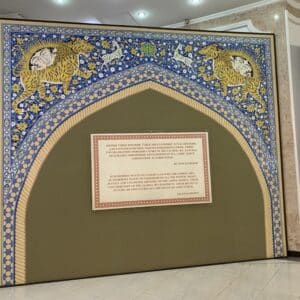

Following Uzbekistan’s independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Timur emerged as a national hero. There is an artifact at the top of the stairs on the second floor of the museum, where Islam Karimov is quoted: “If somebody wants to understand who the Uzbeks are, if somebody wants to comprehend all the power, might, justice, and unlimited abilities of the Uzbek people, their contribution to the global development, their belief in future, he should recall the image of Amir Temur.”*

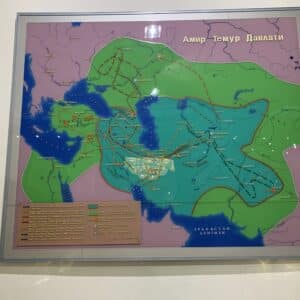

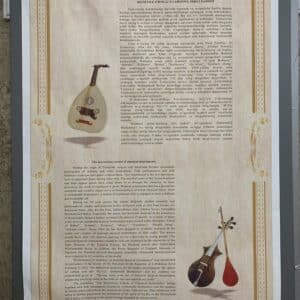

The museum focuses on the positive aspects of Timur’s unified empire and consequent golden age rather than try to give a balanced look at his legacy, which also included bloody warfare and oppression. For instance, the map depicting Amir Temur’s Empire emphasizes the grand scale of his conquered territory. In addition, descriptions of artifacts in the museum often reference Timur’s “Code,” using it to depict him as a compassionate ruler who listened to and cared for the masses. Several instruments on display, such as the flute, doira drum, and violin, emphasize his dynasty’s patronage of the arts. A poster introducing the instruments states that no holiday or celebration could take place under Timur without singers and musicians to entertain the populace. Thus, we are told about the large empire and its renaissance while the historical processes that led to the building of that empire are omitted, giving an entirely positive image.

A Visit to the Museum (2023)

The museum consists of three stories. The entrance is located in the basement, along with the ticket window and restrooms. Visitors enter the main portion of the museum via the grand central hall that dominates the first floor, surrounded by historical murals. Most artifacts and displays are located on the second floor.

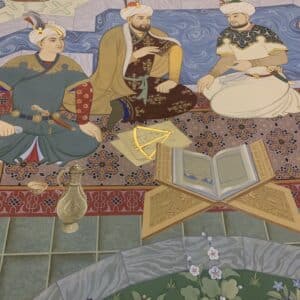

The central hall is decorated with an 8.5-meter-tall chandelier consisting of 106,000 pendants. Amir Timur looks over the hall from a gold-embossed painting. Standing amidst it all is the copy of the 1905 Osman Koran, a ground-breaking document that first tried to unify the teachings of Prophet Muhammed. Islam is an integral part of modern Uzbek culture, and Amir Timur often referred to himself as “The Sword of Islam.”

The museum artifacts on the second floor include archeological and ethnographic materials from Uzbekistan and artifacts from other countries. In particular, exhibits include musical instruments, armory and military weapons, gowns, miniatures of the Timurid dynasty’s constructions, and coins, all representing the Timurid period. Other artifacts, like the zither and porcelain vase, were transported to Uzbekistan along the Silk Road, as Uzbekistan’s cities were a major part of this trading route. Descriptions given for the displays are quite simple, merely naming the objects and sometimes providing dates. More information is provided online through the Nazzar App via QR codes that appear on the protective glass of many artifacts. However, the museum’s wifi connection is not great, so you should not expect to download or use the app if you do not have a strong mobile data plan. At the very least, plan on downloading it before your visit. The app is easy to navigate and has many language options: Russian, Uzbek, English, Kazakh, French, Korean, German, Japanese, Tajik, Hebrew, and Turkish.

The Amir Timur Museum in Context

The museum’s main purpose is thus to impress its visitors and display the beauty and glory of Uzbekistan. It illustrates the larger trend of nation-building following Uzbekistan’s independence in 1991. It is an excellent introduction to the history of Uzbekistan but should be considered only an introduction and an invitation to dig deeper.

* As none of the local languages in Timur’s time used a Latin alphabet, there are multiple transliterations of his name into English. Today, “Timur” is the most common, and we have chosen to use that in this article. However, the museum has chosen to use another variant, “Temur,” in its presentations. We have preserved the spelling here as presented on the plaque mentioned.

You’ll Also Love

Museums as Self-Care

In 2018, doctors in Montreal began prescribing visits to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) for patients experiencing depression, anxiety, and other health issues. This innovative approach to mental health treatment was launched under the initiative of the MMFA in collaboration with Médecins francophones du Canada (MFdC). The program allows physicians to provide patients […]

Guide to Bishkek’s Top Museums for Students

The Kyrgyz were largely a nomadic civilization up until the 20th century. The city of Bishkek has a number of museums documenting this fascinating history as well as the development of the arts and sciences in Kyrgyzstan. These museums were mostly established during (and today are often unchanged from) Soviet times, including a number of […]

The State Museum of Applied Art and Handicrafts History of Uzbekistan

The State Museum of Applied Art and Handicrafts History of Uzbekistan provides an excellent introduction to Uzbek history and culture. Centrally located in Tashkent, it displays more than 7,000 examples of traditional folk art. These include a range of mediums from decorative glass to porcelain and fabrics, all dating from the first half of the […]

Nukus Museum in Uzbekistan: Lysenko, Savitsky, and Preserving the Soviet Avant-Garde

In the remote Nukus Museum of Uzbekistan, a vast collection of banned Russian avant-garde art has been preserved for decades. The museum and its collection were founded by Igor Savitsky, a Soviet artist who defied censors to rescue and safeguard these works. His success was also made possible by the unique geography and history of […]

The Amir Timur Museum in Tashkent

The Amir Timur Museum, also known as The State Museum of Timurids History, stands proud at the center of Tashkent. Built in 1996 to mark the 660th anniversary of Amir Timur’s birth, the museum celebrates what it sees as a glorious history and places modern Uzbekistan as the direct descendant of that history. A visit […]