Moscow’s skyline is largely defined by the seven towering skyscrapers nicknamed “The Seven Sisters.” Also known locally as “Stalinskie Vysotki” (Сталинские высотки – Stalin’s Highrises), they are one of the leading architectural legacies of the Stalinist period. The Soviet Baroque architecture that The Sisters embody is seen by some as unattractive; the buildings themselves are somewhat controversial due to the fact that some see them, with their looming size and sinister-looking spires, as grim reminders of the Stalinist repression. However, while debate still continues on whether these buildings are beauties or beasts, there is no doubt that they have become a major representation of the Soviet era and modern-day Moscow.

Introduction to Moscow’s Seven Sisters

By Hannah Chapman

After WWII, the Commuists had to rebuild large portions of their cities and villages. Stalin believed that Moscow should be updated to compete with the modern cities of the western allies which the USSR had fought alongside. According to nearly all historians of the time, Stalin took a personal interest in each building and argued that if westerners came to Moscow, they would see that Moscow lacked the skyscrapers that western cities of capitalist countries held. This, Stalin believed, would be humiliation.

Stalin enlisted some of the USSR’s top architects to turn Moscow into what he believed would be seen as a contemporary, European city. The crowning glory of this plan was to be eight skyscrapers that would rival recently completed skyscrapers in the USA and Europe.

Stalin’s desire to transform Moscow was not new. The 1930s were a time of active construction and reconstruction of many Soviet cities. Included in these plans was a grand Palace of Soviets, a 415 meter tall structure crowned with a 100 meter statue of Lenin – which would have been the world’s talest building, had it been completed.

Although construction was begun, WWII saw it abandoned and it was never to be realized. However, the grandiose style developed for it was then used as the inspiration for the eight massive skyscrapers. The architects were guided by the The All-Union Academy of Architecture of the USSR, which was created to solidify state control over Soviet architecture in much the same way that organizations had already been created to “organize” the work of writers, actors, and most other creative professions.

Much of Stalin’s personal taste is reflected in the era of “Stalinist Architecture,” a term that has come to refer to the period between 1933 (the year when the Palace of Soviets was designed) and 1955 (when the Academy of Architects was disbanded under Khrushchev). The Stalinist period saw modernity largely abandoned in favor of a combination of Russian Baroque and Gothic styles. This style is exemplified in the Seven Sisters’ trademark “wedding-cake” design with large, stout bases and a sweeping crown. At the peak of each is a central spire. The original plans for most of the Seven Sisters did not include the trademark spire. Reportedly, Stalin took a liking to one that did and subsequently ordered that all of the sisters should include one in part to set them apart from the skyscrapers being built in America at the time.

In 1947, the 800th anniversary of Moscow, Stalin approved Resolution #53 “On the Construction of Multi-Storied Buildings in Moscow” («О строительстве в городе Москве многоэтажных зданий»), while the actual day of the anniversary was commemorated by laying a foundation stone in each of the eight new construction sites. Later that year, construction was begun.

The last of the Seven Sisters was completed in 1957, four years after Stalin’s death. Soon after, the Academy of Architects was abolished and the period of Stalinist Architecture came to an end.

The eighth sister, the Zaryadye Administrative Building, was to be placed in the historic Zaryadye district near Red Square. However, after the district was demolished to make way for it, plans were canceled (partly due to the difficulties of building a massive 32 story building on the soft soil of the Moscow River banks, partly due to a shortage of resources). The Rossiya Hotel, a relatively bland and modern architectural piece, was later constructed in its place (and has itself since been torn down to turned into a massive park).

The Seven Sisters which were completed include Moscow State University, Hotel Ukraina, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Leninsgraksaya Hotel, the Kotelnicheskaya Embankment Building, the Kudrinskaya Square Building, and the Red Gates Administrative Building.

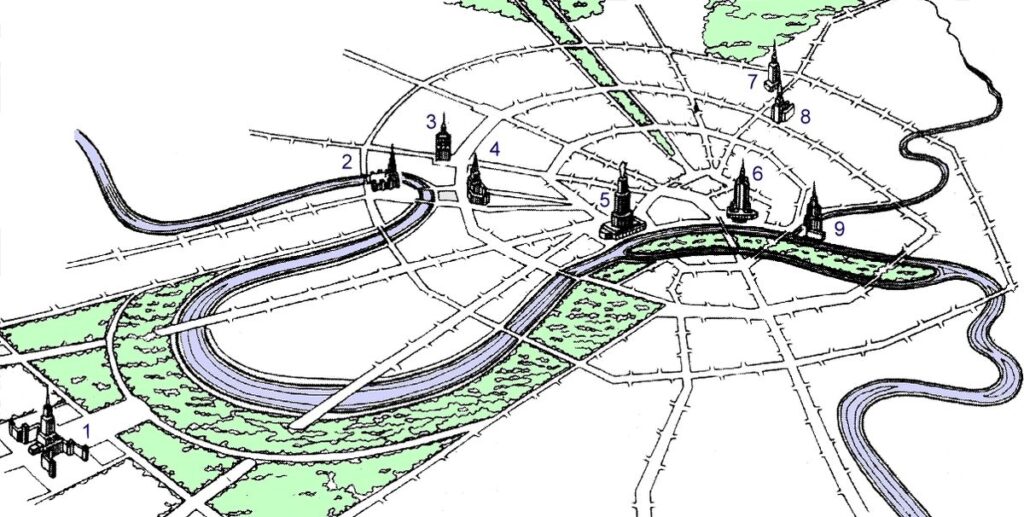

Visiting the towers (at least face-to-face with their imposing facades) is easy. The skyscrapers were built in the form of a ring to emphasize the radial layout of the city. Consequently, The Sisters may best be seen by taking the metro’s ring line. Alternatively, the vysotki may be viewed from afar from Sparrow Hills in the south near Moscow State University where much of the city can be seen at a glance if the weather is clear.

Keep reading to find a description of each Seven Sister, a closeup of the iconic stars they feature, and a description of how to see all seven within 48 hours in Moscow.

Meet Each of the Seven Sisters

By Hannah Chapman

Just as each of Moscow’s Seven Sisters are slightly different and serve different purposes, each also has its own history. Below, we will briefly describe them.

Moscow State University

Московский Государственный Университет

Begun: 1949

Completed: 1953

Height: 240 meters

Use: Student housing, classrooms, offices, etc.

Standing 240 meters tall, Moscow State University (MGU) is the largest of The Seven Sisters. Able to house some 30,000 students, this building has 36 floors and was the largest building in Europe upon its inauguration on September 1, 1953 until 1990 when the Messeturn in Germany was built (256.6 meters).

Boris Iofan, the architect for the Palace of Soviets, was the first architect commissioned to design the plans for what many thought should be the finest of The Seven Sisters. However, he lost the job due to a decision to locate the building on the edge of Sparrow Hills. This ill-fated decision placed the future home of MGU in an area thought to be a landslide hazard. He was replaced by Lev Rudnev who decided to set the building 800 meters further from the ridge and construction was begun in 1949. However, the building still faced hazards from being positioned so close to the water table. This was solved by installing a system of pumps and pipes to continually push water away from the building’s foundation. These pumps continue to operate today to keep the building upright.

MGU was built in part by Gulag prisoners and German POWs, with some 14,290 workers at the peak of construction. These workers were housed on the fourteenth floor so as to prevent their escape – and some rumors say that this floor in the central part of the building is still haunted by their ghosts. One other popular myth describes an inmate trying to escape by creating a wooden glider and flying out of the building.

MGU was the second of The Seven Sisters to be completed. Today, the central tower holds classrooms and student quarters as well as a concert hall, various administrative offices, stores, cafeterias, museums, hair salons, a post office, and a swimming pool (among other things). The four large wings which extend in all directions from the central building hold still more student accommodations, classrooms, shops, and cafes.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs Building

Здание Министерства иностранных дел

Begun: 1948

Completed: 1953

Height: 172 meters

Use: Government offices

Metro: Smolenskaya

Standing just off the famous Old Arbat Street looms the imposing Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Designed by V. G. Gelfreikh and M.A. Minkus, early drafts ranged from 9 to 40 stories, but the building was eventually built with 27. Completed in 1953, it now houses The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and other government offices. This building’s defining characteristic is the huge Soviet crest on its façade which measures 144 square meters in size. The spire wasn’t in its original blueprint but was added later, again, reportedly by Stalin’s personal orders. The spire was constructed with steel framing and, even after painting, remained a slightly different color from the rest of the building.

After Stalin’s death, Minkus wrote a letter to Khrushchev asking for the spire to be removed since it was not part of his original design and didn’t match the rest of the building. Khrushschev supposedly denied this request with the retort: “Keep the spire there as a monument to Stalin’s stupidity.”

Hotel Leningradskaya

Гостиница «Ленинградская»

Begun: 1949

Completed: 1952

Height: 136 meters

Use: hotel and conference center

Metro: Komsomolskaya

This 136 meter, 26-storied building was designed by Leonid Polyakov to be Europe’s finest hotel. Polyakov won a Stalin Prize for the design, but then lost it seven years later after Khrushchev asserted in his 1955 decree “On the Liquidation of Excesses in Design Planning and Construction” («Об устранении излишеств в проектировании и строительстве») that at least 1,000 rooms could be built at the same cost as the hotel’s 354, that only 22% of the total space was rentable, and that the cost per bed was 50% higher than the Moskva Hotel.

Many of these excessses can be seen in the hotel’s ornately decorated interior. For a time, the building was listed in the Guinness Book of World Records for having one of the largest chandeliers in the world: the one that hangs in the main lobby runs the length of seven stories.

After the collapse of the USSR, hotel was purchased by Hilton Hotels and, after major renovations, was reopened with 273 guest rooms in 2008.

Hotel Ukraina

Гостиница «Украина»

Begun: 1953

Completed: 1957

Height: 206

Use: Hotel and conference center

Metro: Kievskaya

The second largest of the Seven Sisters stands at 206 meters tall with 34 levels. It was designed by Arkadi Mordvinow and Vyacheslav Oltarzhevsky. Upon its completion on May 25, 1957, it was Europe’s largest hotel with a capacity for 1,630 people. An observation deck was opened at the top of the hotel in 2004 and it is said that from there one can see all the way to the city’s outskirts on a clear day. It also has a very unique fire-safety system: in the event of a fire, a chute on the outside of the building is opened which allows guests to slide down to safety. The chute is made of kapron, a material similar to nylon, and can hold up to 10 people at a time.

After the collapse of the USSR, the Hotel Ukraina fell into disrepair. It was later, however, purchased by Radisson Hotels. It was closed in 2007 for renovation and reopened in 2010 with two names. It is now still called the “Hotel Ukraine” but also is marketed by Raddison as the “Radisson Royal Hotel.”

Kotelnicheskaya Embankment Building

Жилой дом на Котельнической набережной

Begun: 1938

Completed: 1940

Height: 176 meters

Use: Residential and Commercial

Metro: Kitai-Gorod

Where the Moskva River meets the Yauza River stands the sprawling Kotelnicheskaya Embankment Building.

Designed by Dmitri Chechvlin and Andrei Rostkovsky, the building is 176 meters high with 32 floors, 26 of which are for apartments and the rest for offices and utilities. While the main building was intended as an elite housing project, it was soon turned into “komunalki,” or multi-family living areas in which multiple families were settled in the large apartments. The building is also used for meteorological observations and houses equipment used for weather research.

Red Gates Administrative Building

Административно-жилое здание

на площади Красных Ворот

Begun: 1949

Completed: 1953

Height: 133 meters

Use: Residential, commericial, and offices of the Ministry of Trade.

Metro: Krasnie Vorota

The smallest of the Seven Sisters stands at 133 meters with 24 levels. Designed by Alexei Dushkin, designer of some of Moscow’s most impressive metro stations such as Mayakovskaya and Kropotkinskaya, the building was completed in 1953 and houses administrative offices and apartments. Its right wing houses one of the two vestibules of the Metro station Krasniye Vorota as well as retail shopping space; a children’s daycare center is located in the left wing.

Visitors to the Red Gates Administrative Building will notice that the building is tilted to one side. This is not an optical illusion. The building was constructed with its frame tilted to one side to compensate for the frozen soil below. When the soil thawed, the building settled down but not enough to make it perfectly upright.

Kudrinskaya Square Building

Жилой дом на Кудринской площади

Begun: 1948

Completed: 1954

Height: 160 meters

Use: Residential and Commericial

Metro: Krasnopresnenskaya

Designed by Mikhail Posokin and Ashot Mndoyants, the Kudrinskaya Square Building was intended to house apartments for Soviet cultural leaders.

Its apartments were elegant and the four corners were designed to hold “food palaces” that would be open to all. However, upon the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, this 160 meter high, 22-storied building fell into disrepair. The shops deteriorated and the high-class apartments became cramped one-room units. Today, parts of the building are being repaired and hold stores and restaurants that largely strive to mirror and market the building’s former glory.

Located near the US embassy, it is reported that residents of the top two floors of the Kudrinskaya Square building were evicted durring the embassy’s construction. These floors were then used to house KGB monitoring equipment to eavesdrop on the embassy’s activities.

The Stars of the Seven Sisters

The photos and text in this section originally appeared on The Village in Russian. The text has been translated by SRAS Home and Abroad Scholar Sophia Rehm.

There are stars on only six of the seven Stalinist high-rises, since the spire of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs building was not strong enough to support a star. The stars are all different sizes and shapes, and are made of different materials.

There are perhaps only a few people (a couple technicians, FSB signalmen, and the welder Yevgeny Martynov) who have had the chance to see the spires and five-meter stars of the Stalinist skyscrapers up close. The guys behind Birdseyeview.ru – Sergey Shumilov and Daniil Ananyev – decided this wasn’t fair, and photographed the stars using a professional octocopter (a type of drone), the DJI Spreading Wings S1000, with an attached Sony Nex-5R camera.

Daniil Ananyev, Pilot:

My passion for aerial photography started with a toy helicopter that I crashed on my first day. But I really wanted to look down on the city from above. I found a forum for radio-amateurs, where I discovered drones, spent a long time studying them, and finally bought a small hexacopter with a GoPro camera. I immediately realized that this was my calling. Soon the GoPro’s capabilities weren’t enough for me, and I ordered a copter with a Sony Nex-5 camera. This ended up being a fairly big copter, and it required a second person to control the camera. My photographer friend, Sergey, liked the idea, and we have devoted ourselves to shooting various subjects from a bird’s-eye view ever since. We created the site Birdseyeview.ru, but we can’t call it a business yet – it’s more like a hobby. Once, shooting the MSU building from the sky, we flew up close to its star, and it was such an interesting structure (huge, hollow inside, slightly broken-down). And that’s how our project was born.

Meeting All Seven Sisters in Moscow

By Gregory Tracey

Gregory Tracey studied abroad with SRAS in St. Petersburg. Most programs there include a trip to visit Moscow. This is a recount of his personal experience seeking out the Seven Sisters of Moscow.

Spread throughout the city of Moscow are seven imposing buildings, called variously “The Seven Sisters” or “Stalin’s Skyscrapers.” While visiting Moscow as part of my study abroad experience to St. Petersburg, I wound up setting off on an unexpected mission to see them all that also helped show me much more of this fascinating and historic city than I might have seen otherwise.

While I was aware that such a thing as “Stalinist” architecture existed and while I knew about the unique appearance of the main building of Moscow State University, I had no idea that this matching set of buildings existed. I found that out shortly after arriving to Moscow.

After our train got in, we transferred to our hostel, grabbed a quick lunch and set out for SRAS’ “Walking Seminar: The Origins of Modern Russia.” Our guide, SRAS Assistant Director Josh Wilson, told us about the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Building, visible from a distance from a bridge we crossed as part of that tour. He described it as an imposing, almost scary building that rather embodies how Russia structures its foreign policy: to command respect or, if not respect, then at least awe and a fear of retribution. He recommended seeing the building as an option for spending our free time. This description piqued my interest. I am quite interested in international relations and foreign policy and seeing the building where Soviet and Russian foreign ministers from Vyacheslav Molotov to Sergey Lavrov have worked understandably appealed to me.

On Friday morning we continued exploring Moscow with a tour that included the historic Novodevichy Cemetery followed by a ride in newly-built cable cars up to Sparrow Hills. At this point I saw one of the Seven Sisters up close for the first time: the main building of Moscow State University, located at Sparrow Hills. It seemed quite impressive to me, and from the view from the hills, we could also see more of the sisters on the horizon. I remember thinking vaguely that it could be cool to see all of them, although time could be a factor.

We finished up our tour around 15:30 but I wanted to keep exploring the city (it is not everyday that one is in Moscow, after all). I decided to go ahead and take the metro to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Upon exiting the metro, I turned a corner and was confronted with an absolute monolith of a building. This was the approximate moment when I realized just how impressive these structures are. It is not that easy to take my breath away, but this did it. I stared up at the top floors and the hammer-and-sickle near the top, probably violating my own personal rule to blend in as much as possible and not look too much like a tourist. I could not help myself. I imagined generations of Soviet foreign policy leaders working within those walls on the international crises that I have read so often about in American textbooks.

I decided then that I would see all seven of the sisters. There was really no deep or inspirational motive to this. I just knew they were there, that they were impressive to see, and that I wanted to see them.

As it happened, I moved on toward my goal later that very night. I, along with my friends Morgan and Natasha, decided to go on walk to see Red Square at night. Incidentally, this is quite the experience in and of itself. After walking through the square, we decided to check out Zaradye Park. While there, seeing another of the Seven Sisters, the Kotelnicheskaya Embankment Building again, I explained my “quest” to the others, and they agreed to walk the over to the bridge to see it up close. I was later informed that this could actually have been seen earlier on Thursday, but clearly I had missed it then!

I actually saw this particular skyscraper again, the next morning, during out group tour of the park and the floating bridge over the Moscow River that can be found there. I got some nicer pictures at this point, since I am not very good at getting good photographs at night.

I went into Sunday—the last day of the trip—having only made it to three out of seven. Therefore, I rose early at the hostel despite having been out late exploring the city the night before and found myself at the Red Gates Administrative Building by 07:30. It might have just been the time of day, but the area seemed really quiet and calm. Other buildings are built up quite close, so it also is a little less detached and “aloof.” I snapped some photographs and poked around the area before quickly moving onto the Leningradskaya Hotel, a short walk away. I realized once there that these two are actually right by the Leningradsky Train Station, and I could have seen them on the way back to St. Petersburg (our train arrived there and would depart from there), but no matter. Leningradskaya Hotel was actually probably my least favorite of the seven. It just didn’t look as impressive to me, and it was also hard to see head-on because of the placement of a bridge and some power lines.

I had some other things to accomplish on Sunday, namely a seminar on Russian politics and seeing some museums that I had also planned to take in during my free time. I visited the State Central Museum of Contemporary Political History, a great overview of Russian history from around 1860 to 1991. I also saw the War of 1812 Museum near Red Square, which was also interesting. I particularly found it intriguing how many uniforms and objects from the French Army they had. After leaving, I resumed my mission for the weekend.

Around 14:30 I reached another of the sisters, the Kudrinskaya Square Building. Due to location and appearance, this was probably the second-least impressive of the set from my point of view. I moved past it pretty quickly. On my way away from this one, however, I went past the famous White House, which was far more interesting to see. It is hard to imagine the turmoil of the 1990s, when that building was shelled during a conflict between it and the Yeltsin administration. Today, the grounds are beautifully landscaped and one is looking out at the calm, beautiful Moscow River.

I polished off number seven on the list with seven hours to spare for my time in Moscow. The Hotel Ukraina is located on a gorgeous stretch of the Moscow River. The river location made it probably my joint-third favorite, along with the Kotelnicheskaya Embankment Building. I had some trouble getting to it, as I got a little lost in the pedestrian area of the bridge I needed to take to get there. Unfortunately, the front can only really be seen from the river, but I walked around the base and even noticed a children’s playground. After this visit, I walked along the Moscow River to a more modern set of skyscrapers, the noted Moscow City development. While these are also quite impressive and beautiful, there is still something about the Stalin-era Seven Sisters that feels like it has a bit more character, if that is the correct word for it, than a mass of glass and steel twisting into the sky.

When I went to Moscow, I did not even really know the Seven Sisters existed. But I was, for some reason, inspired to see them all before I left. I still managed to see everything else I wanted, and the experience allowed me to see a lot of more of Moscow then I probably otherwise would have. Plus, I learned a lot about Moscow’s architectural composition in the process. I would definitely recommended taking the adventure to seek them all out. Or, if one does not have the time or inclination to see all of them, I would definitely recommend at least Moscow State University’s Main Building and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as must-sees.

You Might Also Like

The Moscow Metro: From Public Transport to Social Icon

Even if you’ve seen pictures, you’re not prepared for the Moscow Metro System. For visitors, one of the great surprises of this historical city is discovering the beauty and cleanliness of its underground palaces. It’s worth a few hours in the afternoon or late evening (avoid rush hour 4-7) to ride around and see the […]

History of the Kyiv Metro System

Carrying well over a million passengers per day across 52 stations, Kyiv’s metro system is an integral part of the city’s daily life. While it has developed with the ever-growing city, like much of Ukraine’s public infrastructure, the metro system has struggled to keep up with the demands made of it. These demands are growing […]

Moscow’s Seven Oldest Buildings

The following information was taken from a Facebook post by Москва и Москвичи. It has been translated here by SRAS Home and Abroad Scholar Caroline Barlow. Some explanatory text (in italics) and hyperlinks to further information have also been included for those readers who are not well versed in the history of Moscow and Russia. […]