The following bilingual resource is intended to help students of Russian build vocabulary to discuss paintings in Russian. This includes discussing how paintings are created and how they are critically analyzed. As this is a complex field, we have limited discussion to paintings and have omitted prints, drawings, lithography, and other related arts, which may be covered in a future resource or expansion.

Introduction: Names and Tools

When discussing a painting, there are a few obvious things you might mention, such as название картины (the name of the painting) or название произведения искусства (name of the artwork). One might also state имя художника (the name of the artist) or, as we are talking specifically about painting here, we might mention живописец (the painter).

Artists typically use кисти (paintbrushes) but might also use мастихины (palette knives), шпатели (spatulas), тряпки (rags), губки (sponges) or even their пальцы и/или ладони (fingers or hands) для достижения желаемого эффекта (to achieve the desired effects). Paintbrushes themselves come in various forms, including круглые (round), плоские (flat), овальные (filbert), и веерные (fan). More modern artists might use an аэрограф (airbrush), трафарет (stencil), баллончик с краской (spray can), or стилус (stylus).

The surfaces that artists paint on, technically called основы (supports) or поверхности (grounds), can also vary widely and have an effect on the final product. While холст (canvas) is the best known, деревянные панели (wood panels) were often used in in medieval and early Renaissance painting. Icons were sometimes also painted on пергаменте (parchment) or ткани (textiles). Frescoes were painted на свежей штукатурке стен (into the fresh plaster on walls). Many watercolor artists use бумага (paper). Going back to prehistory, our ancestors often used поверхности скал (rock surfaces).

Modern artists have other surfaces to work on. Many modern artists, such as the famous Georgian artist Niko Pirosmani, went undiscovered during their lifetimes and lived lives in poverty. Pirosmani typically painted on cheaper materials such as клеёнка (oilcloth) and картон (cardboard). Artists working in oils and acrylics sometimes now chose древесноволокнистые плиты (fiberboard) or масонит (masonite), which provides a sturdy, smooth, and stable surface. Earlier oil painters often chose металлические листы (metal sheets) for the same reason. Пластиковые или акриловые листы (plastic or acrylic sheets) are sometimes favored by artists working in contemporary mixed-media work.

Other standard tools include мольберт (the easel) and палитра (the palette), as well as стаканчики для смешивания красок (mixing cups) and палочки для перемешивания (mixing sticks).

Types of Paints and Mediums

The artist’s choice of краска (paint) and средство (medium) are also important to the artwork. Artists will often choose paints based criteria like время высыхания (drying time), насыщенность цвета (the richness of the color), and возможность создания текстуры (the ability to create texture). Painting mediums can also be used to alter these qualities in paint. For instance, масло (oil), акриловый полимер (acrylic polymer), or гуммиарабик (gum arabic) can be added to watercolor to make it thicker and richer. Meanwhile, льняное масло (linseed oil) or лавандовое масло (lavender oil) can be added to oils to make them thinner.

In most cases, the terms for various types of paints are derived from the same Latin sources for both English and Russian, making them quite easy to learn and understand:

| English | Русский |

|---|---|

| Acrylic | Акрил |

| Casein | Казеин |

| Digital painting | Цифровая живопись |

| Encaustic | Энкаустика |

| Fresco | Фреска |

| Gouache | Гуашь |

| Mixed media | Смешанная техника |

| Oil | Масляная живопись |

| Pastel | Пастель |

| Tempera | Темпера |

| Watercolor | Акварель |

Types of Paintings

One might also mention the вид живописи (type of painting). In Russian, this can be particularly important as artists that paint in these genres often have specific and idiomatic names. For instance, the Armenian artist Ivan Aivazovsky is considered one of the greatest marine artists in history. He specialized in seascapes and nautical scenes. In Russian, his genre is known as simply “марина” while he himself is a “маринист.” Likewise, a still life in Russian is known as a натюрморт and the artist that paints them can be referred to as a “натюрмортист” or “still-life-ist.” Below are several examples of genres, their Russian translations as well as the term that Russian often uses to refer to the artist that paints within this genre.

| English (Genre) | Русский (жанр) | Художник (специализация) |

|---|---|---|

| Landscape | Пейзаж | Пейзажист |

| Marine painting | Марина | Маринист |

| Cityscape | Городской пейзаж | Городской пейзажист |

| Still life | Натюрморт | Натюрмортист |

| Portrait | Портрет | Портретист |

| Self-portrait | Автопортрет | Автопортретист |

| Seascape | Морской пейзаж | Морской пейзажист |

| Genre painting | Бытовой жанр | Жанрист |

| Historical painting | Историческая живопись | Исторический живописец |

| Religious painting | Религиозная живопись | Религиозный живописец |

| Icon painting | Иконопись | Иконописец |

| Battle painting | Батальная живопись | Баталист |

| Architectural painting | Архитектурный пейзаж | Архитектурный пейзажист |

| Abstract painting | Абстрактная живопись | Абстракционист |

Styles of Painting (up to 1860)

The style of painting is also important. Up to about 1860, styles were widely associated with long historical eras. For instance, Средневековье (the Middle Ages) ran for nearly a thousand years from 500 to 1500 AD. Although the art from this time had some differentiation, if you refer to средневековое искусство (medieval art) your listener can generally conjure an image of what that art should look like (assuming you are clearly talking about Europe, for instance).

Let’s look some major epochs in Russian and English:

| Approx. Dates | English (Art Era) | Русский (период) | Русский (искусство эпохи) |

|---|---|---|---|

| c. 40,000–3000 BC | Prehistoric | Первобытная эпоха | Первобытное искусство |

| c. 3000–500 BC | Ancient Near Eastern | Древний Восток | Искусство Древнего Востока |

| c. 3000–30 BC | Ancient Egyptian | Древний Египет | Древнеегипетское искусство |

| c. 900–323 BC | Ancient Greek | Древняя Греция | Античное искусство (греческое) |

| c. 509 BC–476 AD | Ancient Roman | Древний Рим | Античное искусство (римское) |

| c. 200–600 | Early Christian | Раннехристианский период | Раннехристианское искусство |

| c. 330–1453 | Byzantine | Византийский период | Византийское искусство |

| c. 500–1500 | Medieval | Средневековье | Искусство Средневековья |

| c. 1000–1150 | Romanesque | Романский период | Романское искусство |

| c. 1150–1400 | Gothic | Готический период | Готическое искусство |

| c. 1500–1600 | Renaissance | Возрождение | Искусство Возрождения |

| c. 1600–1750 | Baroque | Барокко | Барочное искусство |

| c. 1720–1780 | Rococo | Рококо | Искусство рококо |

| c. 1750–1820 | Neoclassicism | Неоклассицизм | Неоклассическое искусство |

| c. 1800–1850 | Romanticism | Романтизм | Романтическое искусство |

Styles of Painting (After 1860)

After 1860, urbanization and advances in communication led to an explosion of styles and philosophies about art in what is often referred to as эпоха модерна (the modern era), which refers approximately to time after 1860 or “современная эпоха” (contemporary times), which refers to art created by living artists. Here as well, artists are often referred to by their style. For example, a proponent of футуризм (Futurism) is футурист (a Futurist).

Because of the speed of communication, most terms were adopted quickly from the original source, meaning that they are very similar in English and Russian:

| English (Style) | Русский (стиль) | Художник (в этом стиле) |

|---|---|---|

| Art Nouveau | Модерн | Художник-модернист |

| Color Field Painting | Живопись цветового поля | Художник живописи цветового поля |

| Conceptual Art | Концептуальное искусство | Концептуалист |

| Constructivism | Конструктивизм | Конструктивист |

| Cubism | Кубизм | Кубист |

| Dadaism | Дадаизм | Дадаист |

| Expressionism | Экспрессионизм | Экспрессионист |

| Fauvism | Фовизм | Фовист |

| Futurism | Футуризм | Футурист |

| Impressionism | Импрессионизм | Импрессионист |

| Minimalism | Минимализм | Минималист |

| Photorealism | Фотореализм | Фотореалист |

| Primativism | Примитивизм | Примитивист |

| Pointalism | Пуантилизм | Пуантилист |

| Pop Art | Поп-арт | Поп-артист |

| Realism | Реализм | Реалист |

| Socialist Realism | Соцреализм | Соцреалист |

| Surrealism | Сюрреализм | Сюрреалист |

| Suprematism | Супрематизм | Супрематист |

| Symbolism | Символизм | Символист |

Critical Analysis of Paintings

Critically analyzing a painting means moving beyond simply describing what you see and instead examining how the artwork works and why оно создает определенный смысл (it creates meaning). A strong analysis connects визуальные элементы (the visual elements), технику исполнения (the techniques used), and контекст создания произведения (the context of the work’s creation).

| English | Русский |

|---|---|

| Critically analyzing a painting means moving beyond simply describing what you see and instead examining how the artwork works and why it creates meaning. A strong analysis connects visual elements, technique, and context to interpretation. | Критический анализ живописи предполагает выход за рамки простого описания увиденного и обращение к тому, как произведение функционирует и каким образом оно создает смысл. Убедительный анализ связывает визуальные элементы, художественную технику и контекст с интерпретацией. |

| One of the most important elements to analyze is the use of light. Light can model forms, create atmosphere, and suggest mood. Dramatic contrasts between light and shadow (chiaroscuro) may heighten tension or emotional intensity, while even, diffuse lighting can suggest calm or clarity. Consider the light source: is it natural or artificial, visible or implied? Where the light falls often signals what the artist considers most significant. | Одним из важнейших элементов анализа является использование света. Свет может моделировать формы, создавать атмосферу и передавать настроение. Резкие контрасты света и тени (кьяроскуро) способны усиливать напряжение или эмоциональную выразительность, тогда как ровное, рассеянное освещение может ассоциироваться со спокойствием или ясностью. Важно обратить внимание на источник света: он естественный или искусственный, видимый или подразумеваемый? То, куда направлен свет, часто указывает на то, что художник считает наиболее значимым. |

| Closely related is use of color. Analysis in Russian will often use two different, closely related terms: “Цветовая гамма” and “колорит.” The former refers to the actual colors chosen while the later refers how those colors work together to create an overall mood. Colors may be naturalistic or deliberately distorted. Warm colors (reds, yellows, oranges) tend to advance toward the viewer and evoke energy or passion, while cool colors (blues, greens) often recede and suggest calm, distance, or melancholy. Limited palettes can unify a composition, while sharp contrasts may create conflict or emphasis. | Тесно связана с этим элементом является цветовая гамма. При анализе на русском языке часто используются два разных, но тесно связанных термина. Гамма – это «что» (набор цветов), колорит – это «как» (их взаимодействие и общее впечатление). Цвета могут быть натуралистичными или намеренно искаженными. Теплые цвета (красные, желтые, оранжевые) обычно визуально приближаются к зрителю и вызывают ощущение энергии или страсти, тогда как холодные цвета (синие, зеленые) чаще отступают вглубь пространства и ассоциируются со спокойствием, дистанцией или меланхолией. Ограниченная палитра может объединять композицию, а резкие контрасты — создавать напряжение или акценты. |

| Another key area is composition and shape. Look at how forms are arranged within the frame. Are shapes geometric or organic? Is the composition symmetrical or asymmetrical? Stable compositions can suggest order and control, while diagonal lines and irregular forms often imply movement or instability. Pay attention to how the painting directs your gaze—through lines, repeated shapes, or contrasts of scale. | Еще одной ключевой областью анализа являются композиция и форма. Обратите внимание на то, как элементы расположены в пределах картины. Формы геометрические или органические? Композиция симметрична или асимметрична? Устойчивые композиции могут передавать ощущение порядка и контроля, тогда как диагонали и неправильные формы часто подразумевают движение или нестабильность. Важно проследить, каким образом картина направляет взгляд зрителя — с помощью линий, повторяющихся форм или контрастов масштаба. |

| The use of detail is also revealing. Some paintings invite close inspection with finely rendered textures and surfaces, while others deliberately suppress detail to focus on mood, gesture, or structure. Ask what is rendered carefully and what is left vague. Detail often signals importance, social status, or narrative focus. | Использование деталей также говорит о многом. Одни картины требуют внимательного рассмотрения благодаря тщательно проработанным фактурам и поверхностям, другие же сознательно подавляют детализацию, концентрируясь на настроении, жесте или структуре. Важно задать вопрос: что изображено особенно тщательно, а что остается неопределенным? Деталь часто указывает на значимость, социальный статус или повествовательный акцент. |

| Many paintings also communicate meaning through narrative. Even a seemingly static image may imply a story, a moment before or after an action, or a symbolic event. Consider whether the painting references mythology, religion, history, or everyday life. How do gestures, expressions, and spatial relationships contribute to the story being told—or deliberately withheld? | Многие произведения живописи передают смысл через повествование. Даже на первый взгляд статичное изображение может подразумевать историю, момент до или после действия, либо символическое событие. Стоит определить, отсылает ли картина к мифологии, религии, истории или повседневной жизни. Как жесты, мимика и пространственные отношения участвуют в создании повествования — или, напротив, в его намеренном сокрытии? |

| Finally, consider the theme and context. Themes may include power, identity, faith, nature, labor, or modernity. Understanding when, where, and why a painting was made can deepen analysis. Artistic choices are rarely neutral; they respond to cultural values, patronage, technology, and artistic traditions. | Наконец, необходимо учитывать тему и контекст произведения. Темы могут включать власть, идентичность, веру, природу, труд или модерность. Понимание того, когда, где и с какой целью была создана картина, углубляет анализ.Художественные решения редко бывают нейтральными: они отражают культурные ценности, предпочтения меценатов, уровень технологий и художественные традиции. |

You’ll Also Love

Petersburg with Pushkin’s Bronze Horseman

I’ve been reading works in which Petersburg is mentioned for the past few weeks in order to prepare for this amazing city. It’s been fantastic reconnecting with my love for Russian literature, but things have been feeling slightly off. Every time I walk somewhere, I am just in so much awe at the beauty of […]

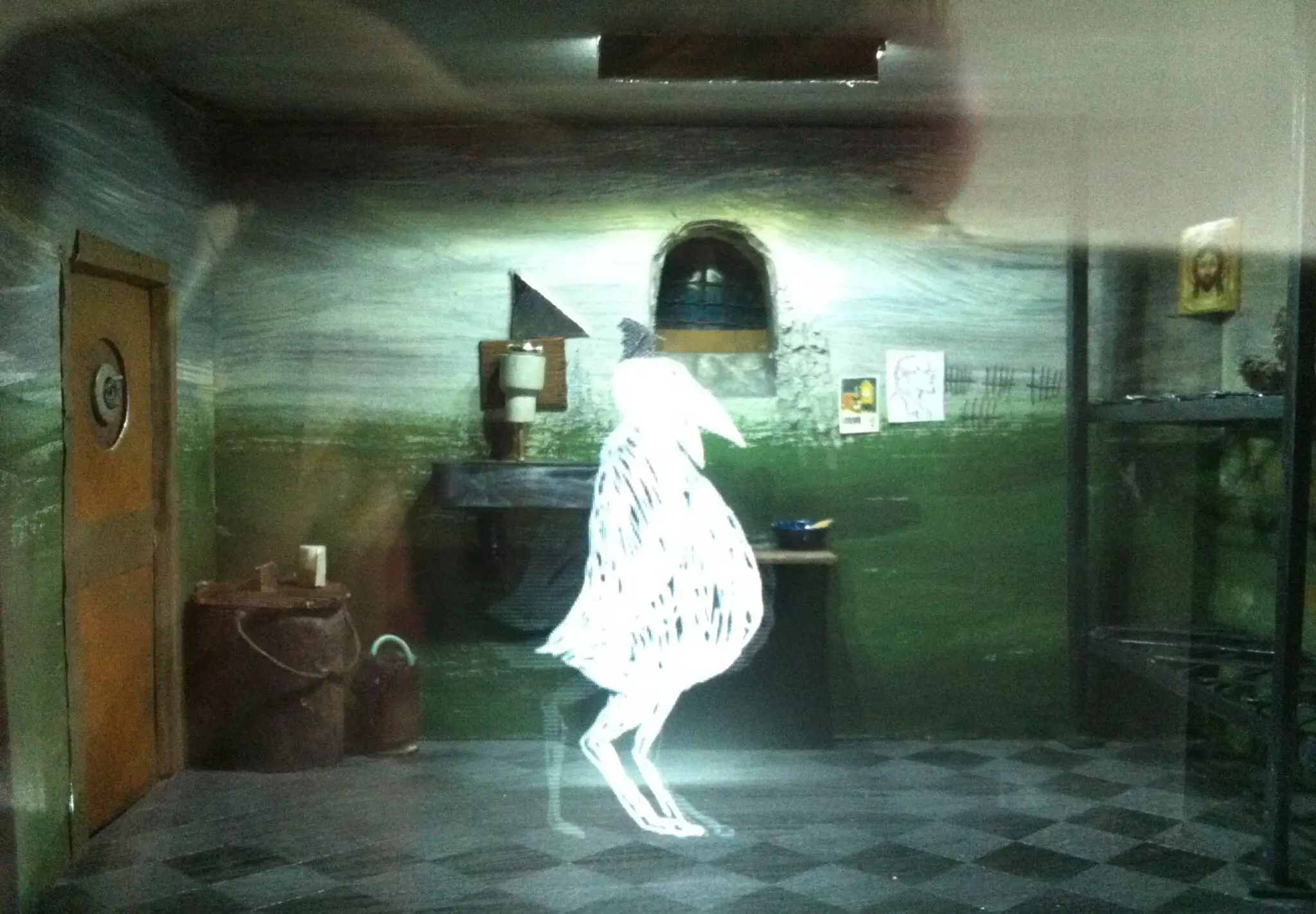

Art Imitates Life(Box): Marina Alexeeva’s “Lifeboxes” at the Marina Gisich Gallery

When you find yourself in front of the Marina Gisich Gallery on Reki Fontaki, it’s difficult at first to tell if you’ve found yourself at one of St. Petersburg’s most significant contemporary art centers, or at a building undergoing major electrical work. The space is currently hosting Marina Aleexeva’s “Lifeboxes,” which features shadowboxes of painstakingly fabricated […]

Kyiv’s People’s Friendship Arch Complex: History and Protest in a Public Space

The People’s Friendship Arch is one of Kyiv’s most iconic and controversial landmarks. The rainbow-shaped arch perches on a hill overlooking the Dnieper River and large parts of Kyiv. “Gifted” to Ukrainian SSR by the Soviet government in Moscow, it remains heavily associated with the USSR, and although it remains a tourist destination and local […]

Russian Crafts Tour the US

This article was originally published on SRAS.org in February, 2006 and was donated to this site at its launch in 2011. The article focuses on the only piece of Russian art to be featured at The Victoria and Albert Museum exhibition called “International Arts and Crafts” in 2006. That exhibit later toured America. In his […]

Irkutsk Welcomes Experimental Artist Sasha Roschin

On Friday, May 11th, the Gallery of Viktor Bronshtaina in Irkutsk premiered its newest temporary exhibit, showcasing the works of Sasha Roschin, an experimental artist and illustrator living in Saint Petersburg. While previously known around the world for his work as a designer and fashion illustrator, recently, Sasha embarked in a new experimental direction – […]