Zakhar Prilepin (Захар Прилепин), born Evgeny Nikolaevich Prilepin in 1975, is an award-winning Russian author, journalist, politician, and activist from the Ryazan Oblast, which borders the Moscow Region in Russia. He is known for both his strikingly realistic writing as well as for his political activity as a nationalist politician and organizer.

Zakhar Prilepin’s Early Life and Education

He has lived in Nizhny Novgorod since 1986 when he moved there with his parents at age 11. His father died in 1992, when Prilepin was 17. Although he has mentioned this fact in several interviews, he never provides details about it.

In 1994, Prilepin was drafted into the army. After his conscription was served, he studied at police school and became a commander of an OMON squad (Отряд Мобильный Особого Назначения; or Special Purpose Mobile Unit), a militarized branch of the police that is used to quell riots and other domestic disturbances. His unit was called up to serve in Chechnya in 1996, near the end of the first Chechen War.

At the same time that he worked with OMON, he studied philology at Nizhny Novgorod State University and graduated in 1999. At this time, he left OMON and started working at newspapers in the Nizhny Novgorod area in hopes of making a better salary. He published most of his journalistic work under pseudonyms such as Yevgeny Lavlinsky (Евгений Лавлинский).

The Novels of Zakhar Prilepin

Prilepin started writing novels after leaving OMON. His first book, Pathologies (Патологии), was based heavily on his experience in Chechnya; his main characters are young men fighting in the same wars that he did. Most of his works are closely related to this same personal experience and reflect the same wartime brutality and violence that he witnessed. Fragments of Pathology were published in various literary magazines before its official publication in 2005, and it was a finalist for National Bestseller in the same year.

His most recent novel, The Monastery (Обитель) won the Big Book Award in Russia in 2014, one award of many for his literary canon. His other novels include Sankya (Санкья, 2006), Sin (Грех, 2007), and The Black Monkey (Чёрная обезьяна, 2012). He’s been a finalist for the Big Book Award, the Super National Bestseller, the National Bestseller, and the Yasnaya Polyana award, all of which are prestigious Russian literary awards run by respected organizations in Russia.

In addition to writing novels, he also has written many essays, short stories, and poems, such as “I Came from Russia” (Я пришёл из России, 2008) and “Boots Filled With Hot Vodka” (Ботинки, полные горячей водкой, 2008). Much of his work is concerned with the changing Russian identity and experience, and he is extremely outspoken about what he views as problematic aspects of contemporary Russia.

Prilepin’s Political and Social Views

Outside of his literary career, Prilepin was also a long-time member of the National Bolshevik Party, a far right political party that was banned in 2007. After the ban, Prilepin continued to support Other Russia, a new political project led by the charismatic former leader of the National Bolsheviks, writer Eduard Limonov. Other Russia activists, many of whom still identify as National Bolsheiks despite the ban, directly participated in Russia’s absorption of the Crimean Peninsula and the conflict in Donbas.

Like Limonov, Prilepin was, especially early on, able to balance his politics with his writing and publish in a wide range of publications from nationalist to liberal and with publications based in Russia, Europe, and the US.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7L2gR-wQ–E

Above: Prilepin is also an actor and produces short films. The above, about a group of rebels in Eastern Ukraine, won an award at the Tribeca film festival in New York in 2018.

As late as 2012, Prelipin was part of the protest movement and publicly called for President Vladimir Putin’s resignation. However, in 2014, after the conflict with Ukraine started, Prilepin has moved to position himself as a less radical and systemic politician, openly voicing support for Putin.

Prilepin joined the All-Russian People’s Front in 2018, a political group started by Vladimir Putin in 2011, and his membership with The Other Russia was revoked due to the contrasting ideas of the two groups.

In 2020, he was named to the committee that wrote the amendments to the Russian Constitution adopted that year.

Also in 2020, he co-founded a political party called For Truth (За правду), which is nationalist and center-right. It supports a paramilitary group called Prilepin’s Guards that continue to support the rebels in Donbas. He has publicly boasted about the violence done by his group in the area and he is currently banned from both Ukraine and Bosnia-Herzegovina for security reasons.

He also runs the Humanitarian Assistance to Donbas Foundation, linked to from his personal website and currently accepting donations, to send food, clothing, and other supplies to the people in Donbas affected by the war.

Ahead of the 2021 parliamentary elections, his For Truth Party has formed an alliance with the systemic Just Russia Party, meaning that Prilepin’s new political vehicle will likely hold at least some legislative representation by 2022.

Prilepin’s Social Positions

Prilepin’s political positions and paramilitary activities now led to his artistic work being relegated to more national venues inside of Russia. His publisher in Germany has intentionally distanced itself from Prilepin and currently donates profits from his work to Amnesty International. English translations of his novels have also almost entirely stopped.

He remains unapologetic about his beliefs. Furthermore, his works are still considered extremely significant to contemporary Russian literature, and he still holds a substantial platform in Russia, remaining a cultural fixture in the country throughout his political transition.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XdiPmSqzMhs

Above: Prilepin participates in a 2021 televised debate for the upcoming Duma elections. He discusses several issues and debates them, in Russian, with a representative of the ruling party, United Russia.

He has hosted cultural programs on various Russian TV stations, including a music focused show called Salt, on then-popular REN-TV station, and later, another called Tea with Zakhar (Чай с Захаром; in Russian, it sounds very close to “tea with sugar” – чай с сахаром). The latter was a talk show on the Internet TV channel Tsargrad where he interviewed people about politics, art, and literature.

Currently, he is host of Zakhar Prilepin’s Russian Lessons, a sort of political blog that has aired weekly on NTV in Russia since 2017. He is the Assistant Artistic Director at the Gorky Moscow Art Theater in Moscow and the Editor in Chief of the internet publication Your News (Ваши Новости).

Further, his political party has garnered enough celebrity support and public following to establish itself in dozens of Russian regions and set it on course to unite with a long-standing systemic party and towards political representation.

Thus, while his activities may now be confined to Russia, he has certainly not slowed down.

Political Themes in Prilepin’s Work

Prilepin’s work does sometimes tend to reflect his personal views. In the case of his novel The Monastery, only one woman has a name, and she is the love interest of the male main character. Many of the characters fall directly within harmful stereotypes: women are silly and self-absorbed, and the facial features of Jewish people are often specifically described as exaggerated.

His unapologetic support of Stalin’s historical memory is present in his novel Sin, where a character, named Zakharka––a soldier fighting in one of the Chechen wars––chants in support of Stalin, likening him to the homeland of Russia. At the Gorky Moscow Art Theater, where Prilepin is Assistant Artistic Director, a play about Stalin called The Wonderful Georgian is also being produced.

In Sankya, the epynomous main character expresses disgust at the idea of a Russia populated entirely by “the Chinese and the Chechens,” and none of his companions act as though this xenophobic idea is out of place.

However, despite undercurrents of racism and xenophobia present in his writing, many Russian and foreigners alike overlook Prilepin’s nationalism and praise his descriptions of a troubled Russia seeking a new identiy while living through extraordinary political and cultural situations.

To take Sankya as an example again, many people have found it a relatable description of the generation of Russians born at the end of the Soviet Union. In the introduction to the English version of Sankya, Alexei Navalny writes, “If you want to feel the raw nerve of modern Russian life, what you need isn’t Anna Karenina – what you need is Sankya.”

Reviews of Sankya often praise the main character as “raw” and “real” despite of – or perhaps because of – his violence and xenophobia, perhaps seeing it as a product of the chaotic times he lived in.

Prilepin is an extremely interesting case of separating art from artist––many people in Russia and worldwide are at odds with his nationalist views––some of which are present in his work––but his novels are still considered some of the best of the past decades, and many find solace in his exploration of Russian identity. Nonetheless, he remains an important figure in modern Russia and likely will continue to be.

You Might Also Like

Boris Akunin: Nom de Plume, Nom de Guerre

In an interview with the Financial Times, Grigory Chkhartishvili was asked how his Russian upbringing stimulated his creativity, to which he responded: “I have the impression that if you were born in a calm country you could live until 90 without discovering who you really are because life does not test you so harshly. In […]

Dmitry Glukhovsky: Viral Literature

In an interview with the French art blog Adria’s News, Dmitry Glukhovsky was asked why he continued to post his literature online, to which he bluntly replied: “I want my books to spread like a virus.” With over five million free downloads of his novels, in 37 different languages, as well as in print, not […]

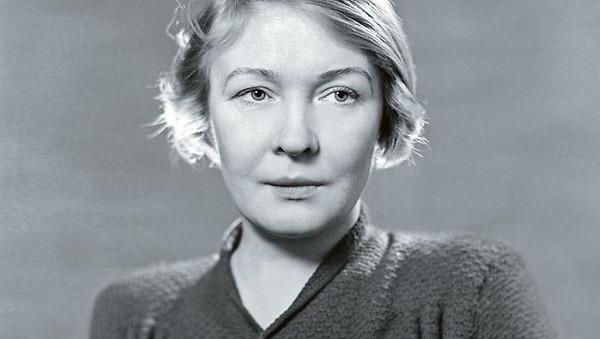

Olga Bergholz: “The Voice of the Blockade”

During the Siege of Leningrad in 1941, Olga Bergholz became a voice for the citizens trapped within the city. Reading her powerful poetry and flowing speeches over the radio waves and through loudspeakers, she captured with honesty the brutal reality of the Siege – including life, death, starvation, and the horrors of war. Not only […]

Tatyana Tolstaya: From Sightlessness to Imagination

Before the invention of laser eye surgery to correct vision impairments, Tatyana Tolstaya was faced with a tough decision: suffer through poor vision, or undergo a long surgery involving medical razors. She chose the latter. Through a long convalescence, her eyes covered and unseeing as they healed, she was surprised to discover an “aetherial world […]

Dmitry Bykov: History and Irony in the Spirit of Protest

In an interview in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Dmitry Bykov was asked what he thinks the role of the writer is in today’s society, to which Bykov responded: “As Strugatsky said, ‘To see everything, to hear everything, to understand everything.’” In his career, Bykov has certainly taken this quote to heart. He is […]