When most think of Russian protest art today, they think immediately of Pussy Riot, the long-famous, all-female punk movement. These women have, since their “punk prayer” launched them to international notoriety, been heavily covered in the English-language press and heavily studied in English-language academia.

However, Russian protest art is a diverse genre with a long history and many active practitioners. The following is a description of six major Russian protest artists of the post-Soviet era.

Sergei Mironenko and the Mukhomor Group

By Elizabeth Rodgers

Sergei Mironenko began as one of Russia’s semidesyatniki – a group of artists who fought for expression during the “stagnant era” of the 70’s. He was educated at the Gorki Theater Academy of Art in Moscow and graduated from the Theater department at MXAT in 1981.

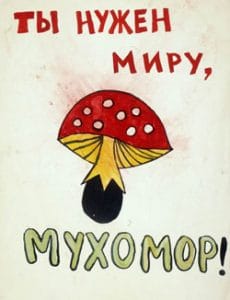

Mironenko began his artistic career in 1978 when he joined a group called the Mukhomor (“Toadstools” in English.) Other members included Sven Gundlach, Konstantin Zvezdochetov, Alexei Kaminski and Vladimir Mironenko (Sergei’s twin brother). This anti-establishment collective dabbled in various forms of art including writing, performance, graphics, painting, and music. They wrote and bound their own books of poetry, made posters and put on performance art skits. In 1982 they released a musical piece entitled Golden Disk which launched them into a brief super-stardom. The production, quickly banned in the USSR after being played on the BBC, featured the young artists reading poetry over a diverse collection of world music. Included in the musical mash-up were the groups Shocking Blue, ABBA, and Stasa Namina, but also the ringing of the Kremlin bells, Verdi, Arabic melodies, blues improvisation, country, jazz standards, and fragments from the symphonies of Chekhov and Beethoven.

Despite the fact that none of the members of the group had any particular musical talent, the poetic piece attracted an avid cult following. Soon they were ranked on a par with Pink Floyd on Russian musical charts. The Mukhomor handled the idea of being pop stars like it was any one of their other conceptual art projects, and they continued to put on skits and write poetry. Using the Futurists of the 1910s as an example, they turned their own image into an earnest art project. Konstantin Zvezdochetov declared: “We are not concerned with art. Our main work – is our existence.”

One description of a Mukhomor exhibit shows the attention given to the experience of the audience. Evidently at one showing the Mukhomor group hid behind a large spread of white paper. They began tearing the paper apart slowly from behind. After a while, they projected a seascape on the white paper, also from behind. As the paper came down, the seascape became little by little projected on the audience rather than on the “canvas.” As the paper came apart, they threw torn-off pieces and poured water through. Throughout, a low hum of words and other sounds was played as a background – this was the sea babble, which the audience described as lulling and soothing. The experience of the audience steadily became the work of art – as if the art clawed its way from the canvas in order to insinuate itself into the lives of the viewers.

Mironenko stopped his work with the Mukhomor in 1984 and became more involved with the unofficial or nonconformist artists. He participated in several Apt Art exhibitions – which earned their name by traditionally being held in apartments. The Apt Art movement, which ran from 1982-1984, was differentiated by its inherent embrace of conceptual art. The artists would frequently use their setting as a ready-made artistic commentary on the stagnancy induced by the shortcomings of state reform. Mironenko was among the first to exhibit on Furmanny Lane, a small street in Moscow in which unemployed artists would alternate between squatting in dank basements and holding sincere art showings.

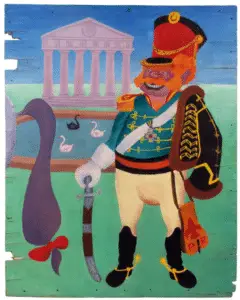

Mironenko had long been a conceptualist, but around this period he became more involved with the Sots-Art movement, Russia’s answer to American Pop-Art. The movement in America largely came as a reaction to commercialization and the heavy presence of marketing slogans in daily life. In Russia, the slow dismantling of the reign of Socialist Realism and its counterpart propaganda left ample material and a ready-made canvas for ironic art. Sots-Art subverted Russian propaganda, Socialist Realism and other forms of government repression.

Mironenko entered Sots-Art with an artistic background in Theater, writing, painting, and conceptual Apt Art installations. His Sots-Art work consequently drew from a broad spectrum of influences. In Area Hero (1988), Mironenko displayed an actual hospital bed for war veterans with the inscription “Area Hero”. The words underlined the irony of the state’s treatment of veterans while turning traditional propaganda on its head.

In Presidential Election Campaign (1988) he showed an accurate, almost full-size election billboard, on which the artist himself is nominated for President. This expressed the feelings of freedom brought about by the election as well as the freedoms of expression allowed by perestroika and glasnost. However, a desk placed before the billboard bore, in place of an uplifting campaign slogan, the words “What have these swine done to our country?”

While in both cases the words intone Sots-Art irony, the mentality that everything is stagecraft and that the audience is complicit can be clearly traced back to Mironenko’s days with the conceptualists and the Mukhomor. In both Area Hero and Presidential Election Campaign, the art is not framed or emotionally distanced from the viewer as “art.” Instead, the viewer is made to feel as if he or she is being confronted with an actual scenario. It’s as if a real part of life is being subtitled and turned upside down. This interactive element has become a staple of Mironenko’s work.

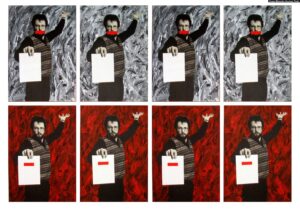

Throughout the 80’s and 90’s Mironenko participated in exhibitions both in Russia and abroad. In addition to his installations, he also produced many Sots-Art paintings, usually red print on black drawings apparently in the style of traditional Socialist Realism.

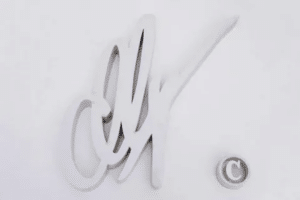

His 1992 piece, Signature – essentially a canvas in the shape of a signature and copyright insignia– was a comment on the supreme importance of monetary value within Pop-Art and Sots-Art. In calculating the worth of Sots-Art and Pop-Art pieces, the all-important consideration was the presence or absence of the artist’s signature. Hence, Mironenko cut out the middle man (the art) and simply made the signature into the exhibited piece.

In 1995, he began to pursue design but he returned to “high” art in 2003 with Apartment Exhibition. Since then, he has shown his work several times. First, in 2006 he exhibited at Artists Against The State: Perestroika Revisited at Ronald Feldman Fine Arts Inc. in New York and “Handle with care: glass” at Moscow’s Pushkin State Museum of Fine Art.

In 2007 he participated in Sots Art. Political Art in Russia from 1972 up to Today at the Maison Rouge in Paris. In his 2009 he exhibited at the Aiden Gallery in the Third Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art. At this latter show, his installation was entitled Elements, and it featured a wall-spanning periodic table of fake elements including Comfort, Illusion, Fiasco, and Patiency. On one wall is an enormous poster reading: “Falsification: The Accelerator for Filling in Spaces.”

Of this installation, Mironenko said: “Spectators are always in dialogue with the product and become, in essence, an integral part, as a result of their interaction and there is something that can be called art or, conversely, can not be labeled as such. [. . .] The work appeared [to be an] orderly system in the form of a table of elements, packaged for easy understanding in the form of the periodic table, but [was] filled with other domestic content.”

The discrepancy between what one expects and what one gets is important in Mironenko’s work because of the high value he places on the thought processes of the viewer. A large part of his art exists within theses struggles to comprehend. The viewer either accepts the art or rejects it, but either way he or she is pulled into a dialogue.

Today Mironenko remains an active artist and active protestor, often creating anti-Putin images and artworks commenting negatively on the status of modern Russian society.

Elena Kovylina – Constructive Performance Protest Art

By Taryn Jones

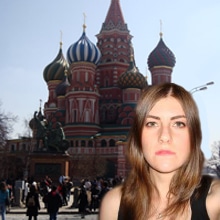

Elena Kovylina was born in Moscow on November 22, 1971. She became one of the most brilliant Russian artists of the twenty-first century, as well as an aggressive social critic. She currently splits her time between Western Europe and her homeland, and has studied at Zurich’s F+F Schule fur Kunst und Mediendesign. It was in Switzerland that she first became interested in performance art, which ultimately became her preferred medium. Although a prominent performance artist today, Kovylina was not even aware of the medium’s existence at the outset of her career. While at the F+F Schule, she studied a variety of subjects, from radio to Theater to photography, but performance art became her true passion as it allowed her to be script writer, producer and player. She recalls that “performance as medium struck me with its versatility, its ability to react quickly to social contexts and to different situations. It seemed to bring together all my interests: visual arts, film, Theater, activism.”

Kovylina’s interest in art began at an early age, and she attended Мoscow’s Memory of 1905 High School for Visual Arts from 1988 to 1991. Upon graduation, she progressed to the Surikov Art Institute, where she studied until 1995. During this time, she received a classical Soviet art education, involving both art history readings and “boring exercises in drawing nude workers and executing colourful landscapes,” in an intellectual and artistic atmosphere that she has described as “oppressive academism” In total, she received thirteen years of such education, and by the time she was accepted to the Zurich institute in 1996, she was establishing herself as a socialist-impressionist painter. She was shocked, however, to discover that her Swiss instructors considered her works to resemble those painted by their grandparents, and in turn they were surprised to hear that she had never encountered artists in the style of Joseph Beuys, a German graphic and performance artist who is now considered to be one of the twentieth century’s most influential artists. In 1999, she completed a course on new artistic strategies at the George Soros Centre of Contemporary Art in Moscow.

Kovylina’s performances are often characterized by their ‘in-your-face’ aggressive attitude that forces spectators to confront clichés head-on. There are often overtones of eroticism in her work as she frequently uses her naked body as canvas. Kovylina’s performances seek to engage and create a relationship with her audience, while still attempting to portray real-life experiences based on issues facing Russia today.

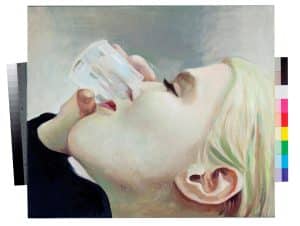

Her physically demanding performances spare neither herself nor her spectators, a fact which is clearly demonstrated in both Boxing and Waltz. In Waltz, created in 2001 and her only piece to be seen thus far in the United States, she invites spectators to dance with her, and she herself dances until she nears the point of collapse. Throughout the piece, she decorates herself with military badges and downs shots of vodka, becoming increasingly intoxicated, eventually stumbling and nearing incapacitation. Understandably, it is physically demanding, and it usually takes her several days to recover from the performance, which is the primary reason it is rarely seen.

In her 2005 piece Boxing, she interacts with the audience by encouraging them to fight with her, and the fights themselves are refereed by other members of the audience. She never knows whether she will win or lose, and her aim is to focus attention on the plights of violence and victimization. Her art has not only helped her to define problems facing Russian society today, but also to redefine herself. In order to create her pieces, she has had to locate herself within the broader social context as both a Russian and a post-Soviet.

Kovylina’s performances are often scathing in their critiques of modern Russian society, and her unique experience of growing up in the Soviet Union, pursuing a western European contemporary art education and living in post-Communist Russia have influenced her work considerably. It is perhaps surprising that there hasn’t been more criticism of her work, as she does not shy away from open social and political commentary, but she is more likely to critique than to be critiqued. Despite the Moscow Actionists’ introduction of performance art to Russia in the 1990s, it appears that her work is still generally poorly understood in her home country.

Although there has been little official criticism of her performances, her work is not without risks. While performing one of her pieces in Russia, an onlooker attacked her, yelling, “What’s going on, this isn’t art, this is shit!” It was only thanks to another onlooker who defended her right to perform that she escaped unharmed. Kovylina was later accused of setting up the incident as part of her performance, although she denies these claims.

In 1998, while performing “The Rate of the Ruble” (Курс Рубля), her first piece to be performed in Russia after her return from Western Europe, Kovylina was taken into custody after taking her piece to the Central Bank, and attempting to speak with the director. After being refused, she exclaimed, “Long live the Russian ruble! Hurrah!” A crowd had followed her but she was immediately arrested. Soon thereafter she was released.

In 2008, Helsinki played host to a video installation of Kovylina’s work entitled Dying Swans. The piece is an open criticism of contemporary Russian society of the state’s attempts to control mass media in order to regulate what image of Russia is portrayed to its citizens and the world. Dying Swans was created to pay homage to the over 200 reporters who were murdered or who have simply disappeared in the last decade, and the inspiration is drawn from the Soviet tradition of playing Swan Lake after the passing of influential statesmen. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the carefully-crafted portrayal of Russian high culture took a backseat to the media’s attention to more pressing matters, and so the most effective way of controlling what the world saw of the new Russia was by heavy control of journalists. Coming two short years after the high-profile death of Novaya Gazeta journalist Anna Politkovskaya, the installation was, perhaps unsurprisingly, displayed in Switzerland, France and Finland, yet Moscow galleries refused to show it.

Another of the major themes running through Kovylina’s work is the role of women in modern Russia. In Pick Up a Girl, a reinterpretation of Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece, she encourages spectators to choose a magazine cut-out from a selection that she has affixed to her body with surgical needles, and then instructs them to discard it. Although inspired by Ono’s work, she wants her audience to throw away the photo rather than keep it, in order to highlight the situation of women residing in post-Communist Russia.

Yoko Ono is not Kovylina’s only source of inspiration. She is also aware of, and inspired by, the works of Arthur Cavan, Marina Abramovic, Avdey Ter-Oganyan, Anatoly Osmolovsky, Oleg Mavromatti and even Malevich, whose own funeral is considered by some to have been a piece of performance art. She has been particularly influenced by Alexander Brener, which is apparent in the aggressive way that she approaches her audience. Like Brener, she challenges the outside world both mentally and physically. Thankfully, unlike Brener, she has confined her performance activities to challenging spectators, rather than having sex in city streets or defecating in front of priceless artworks. She credits the Moscow Actionist movement of the 1990s for creating an intellectual climate in which performance art can thrive. However, her works have a more planned structure, and she performs just within the bounds of the law, often unlike the Moscow Actionists.

In recent years, Kovylina has become a mother three times over. This has not slowed her down much as she continues to pursue grants and exhibition opportunties worldwide. In 2014, she completed a master’s degree in art history from the Russian State University for the Humanities, writing her thesis on the use of images in XXI century performance art. She has also used her fame to not only teach performance professionally through masterclasses but also support The Theater of Homeless Youth. Since 2019 she has been the curator of the Khodynka Gallery, part of the system of galleries operated by the City of Moscow.

Elena Kovylina is an example of a protest artist who has managed to take on tough issues while remaining within the law and even generally within the good graces of the government. She seeks not only to critique, but to also to build and improve the situation around her. Her pieces continue to represent a fresh and critical view on issues facing Russia today.

You can find her on Instagram and Facebook.

The Blue Noses – Satire and Lampoon in Russian Art

By Taryn Jones

The Blue Noses, an artistic duo consisting of Alexander (Sasha) Shaburov and Vyacheslav (Slava) Mizin, was founded in 1999. The group is known for their satirical and oft-times provocative works, which encompass photographs, videos, and performances that parody and critique Russian society, art, politics, and religion. Their message seems to be simply that nothing should be taken too seriously.

Using decidedly low-tech methods in their artistic endeavors, their works are often marked by black humor and some have labeled them as modern-day yurodivy, street people who, during medieval times, were believed to both insane and touched by God. “For me, I don’t like this kind of art. They’re trying to represent the ironic tradition, called yurodivy, which is well known here and characteristic of the Middle Ages,” noted Moscow-based art critic Misha Sidlin in 2006 to N. Fitzgerald, quoted in “The pranksters of the Russian Art Scene: 3 edition” by the International Herald Tribune, pp. 9. However, despite his stated dislike for the duo, he recognizes that the Blue Noses have a unique talent for livening up ordinarily sleepy biennials with a brand of humor that everybody understands.

The group was born when Shaburov and Mizin, working together on a millennium project entitled Shelter Beyond Time, took up residence in an underground bomb shelter to experience life as it might be after a nuclear disaster.[2] Inspired by the fears surrounding the so-called Y2K disaster, the pair spent three days in an abandoned bomb shelter in the center of Novosibirsk without clocks, alcohol, or contact with the outside world. Although they originally intended to live without technology of any sort, one of the artists broke the rules and smuggled in a video camera. As boredom set in, the two filmed so-called “absurdist video gags,” which included placing blue bottle caps on their noses, and so the group “The Blue Noses” was born.

Although they initially had some doubts about working together, as both wanted to pursue individual art careers, they were once more pushed together at a biennale, when they both discovered that their hotel had no record of their reservations under their individual names. Rather, they were listed under the group name “The Blue Noses.”

In an interview with Voina’s (a Russian protest art group described below) Alexei Plutser-Sarno, Shaburov stated that, “until about the age of 30, like all normal artists, we didn’t consider each other to be artists. Each thought that he was the best, and nobody else was any good! Slava is from Novosibirsk, but then he moved to Sverdlovsk… However, when we both moved to Moscow, it seemed that they didn’t distinguish between Sverdlovsk and Novosibirsk, the Urals and Siberia.” Since 2000, the two have worked together to produce politically and socially controversial art.

Sasha Shaburov was born in Sverdlovsk Oblast in 1965, and graduated from Sverdlovsk Art School in 1985. After graduation, he worked for a time as a mortuary photographer, but by the late 1990s shifted his focus to creating art from everyday situations. In 1998, he received a grant from the Soros Foundation to have extensive dental work performed on himself and photographed into a series which he entitled “Teeth Filling and Fitting.” From the look of the pictures, it may well have been his first trip to the dentist ever.

Slava Mizin, who was born in Novosibirsk in 1962 and graduated from the Novosibirsk Architectural Institute in 1984, also saw his body as an artistic canvas. However, this realization was the result of drunkenly passing out in a snow drift and suffering from a frost-bitten lung. After this period, he started a series of works known as Fate, in which he placed his penis on various objects and photographed it, creating a “mythological life cycle” for it.

Perhaps the duo’s most well-known project is the photograph, “Era of Mercy,” which features two Russian policemen locked in a passionate embrace in the midst of a snowy birch forest. The color photograph, shot in 2005, is now in the possession of contemporary art collector Igor Markin. The piece was reputedly inspired by British street artist Banky’s “Kissing Policemen,” which, although defaced by vandals, was protected and became a point of pride for Brighton, the city in which it was painted. Although set to be displayed in Paris at a SotsArt display in 2007, Era of Mercy was detained by then Culture Minister Alexander Sokolov, who labelled the photograph erotic and a disgrace to Russia.

Consequently, the photograph remained in Russia and was not displayed in Paris, although it did make the front pages of several international papers, perhaps garnering more global attention than it would have had it been displayed without fuss in Paris. However, in an ironic twist, the same piece had been displayed by Moscow’s presitgious Tretyakov Gallery and Andrei Sakharov Center earlier in the year. The photograph also enjoyed a degree of support from certain circles in Russia. At the opening of the 2007 Kandinsky prize ceremony “two threatening police officers entered the hall from opposite sides. They moved to the center of the stage, embraced and passionately kissed as the crowd burst into applause.”

Also in 2005, the duo created another controversial photograph with their piece entitled Chechen Marilyn. Modeled after the (in)famous photograph of Marilyn Monroe on a heat vent, the photograph depicts a woman dressed in a black burqa, her hands holding it down while the bottom flares up and out in the style of Marilyn’s famous photograph. That photograph was also displayed at the Sakharov Center’s exhibition of banned art alongside Era of Mercy. After court proceedings, both Yuri Samodurov, the then director of the Center, and Andrei Yurofeev, the show’s curator, were found guilty of “inciting religious and ethnic hatred,” although neither was sentenced to prison.

The Blue Noses found themselves at the center of a debate on what constitutes religious freedom and freedom of expression in contemporary Russia, a seemingly odd position for two artists who have been described as the ‘Dumb and Dumber’ of the Russian contemporary arts scene, as spelled out by N. Fitzgerald in his 2006 piece for the International Herald Tribune.

In 2006, authorities detained a shipment of works destined for the London gallery of art dealer Matthew Bown, including the 2001 photograph Mask Show. The piece features three men clad only in their underwear posing languidly on a couch wearing masks of Putin, Bin Laden, and George Bush.

The shipment of works also included “Chechen Marilyn,” although it appears to have been the portrayal of political leaders that caused the most interest amongst customs officials. Bown reported that he was told by the customs officers that the works “contain representations of heads of state and this could not pass unnoticed,” despite the fact that he had all the legal documentation required to export art works out of Russia. The detainment led to an investigation, and the day after Bown was stopped at the airport, the Moscow gallery from which the pieces were loaned was attacked.

The group also takes on slightly less serious topics, and enjoys irreverently poking fun at the Suprematist art movement, founded by Russian artist Kazimir Malevich in 1915. This is consistent with their parodies of Russia, past and present. In their 2005 series, Kitchen Suprematism, they photographed black bread, cheese and deli meat arranged in abstract geometric shapes that echoed Malevich’s works. In an earlier series of works dating to 2003 known as Sex Suprematism, they appropriate traditional Suprematist motifs in order to create bodies, and featured photographs of their heads with comic-book style dialog bubbles uttering sexually-provocative phrases.

Despite lamenting that they have never seen a KGB agent, they have found themselves at the center of several controversies. However, they have continued to create low-tech, populist art. Art collector Igor Markin has stated that “’their humor is understandable but deep in the Russian soul. Not everyone gets the Blue Noses, because they make work that is a joke.”

P183 – Russian Protest Art Takes to the Streets

By Kristin Torres

“I believe all art should be anonymous,” Pasha 183 told Interview Magazine in 2012. Thus, little is known about him, since a life of anonymity was necessary for the Moscow-based street artist, who also went by P183. Russian and British press peg his age at death in April, 2013 as 29, and note that for his young age, his street art career spanned 15 years. The only other fact known about the artist is that he studied “communicative design” at university. It is rumored that his real name is Pavel Pukhov.

P183 is often referred to in the press as “the Russian Banksy,” and his works are often compared with those of the famous British street artist. Even in Russia, P183 remained relatively unknown outside of Moscow until the press began reporting on his works in 2012. The Guardian in the United Kingdom was one of the first press outlets to cover P183’s work and to make parallels between the two secretive street artists. P183, however, refuted in several interviews any notion that he took his inspiration from Banksy, though he conceded shared objectives with his artistic counterpart. “I fully understand that we both have a common cause, but I never sought to emulate him or anyone else,” he told The Guardian in 2012.

In discussing the similar black-and-white aesthetics of both artists works, P183 told Interview magazine that he lamented the fact that the media treated Banksy as if he had a monopoly over street art. “Any stenciled, black and white picture on the wall today is associated with Banksy,” P183 said. “I always drew black and white characters. I had a period when there was simply no money for paint, and the only thing I could afford were the cans of back and white.”

P183 says his interest in street art began while he was a pre-teen boy, writing poems and drawing pictures on Moscow’s Tsoi Wall, which commemorates the much-beloved front man of Soviet rock group Kino. Growing up in a big city, graffiti was a common sight for P183, as was the rise of post-Soviet consumerism and advertising. Many of P183’s works address the omnipresence of commercial advertising, and made clear his views on mass consumerism.

In one piece, September 2012’s About Advertising, the artist set up an installation near a Moscow park where the artist’s versions of advertisements and logos were stenciled onto concrete. Nearby, he positioned a life-sized black-and-white cutout of a man vomiting a stream of white, which then becomes the stream of white paint on the concrete ‘crossing out’ the advertisements and logos. A video of the artist installing the work can be seen here.

Another strong commentary was November 2012’s Zoo. In this installation, the artist took to a pedestrian walkway near a construction zone and turned it into a zoo exhibit. The walkway had been haphazardly fenced in with wire and the artist envisioned it as not unlike a cage. Against the wall, he hung a giant banner depicting monkeys that stretched the length of the walkway, and hung bunches of bananas from the walkway’s wire fence. As people walked through the walkway, it became a visual pun, likening the pedestrians to monkeys in the zoo. A video on the installation’s construction can be seen here.

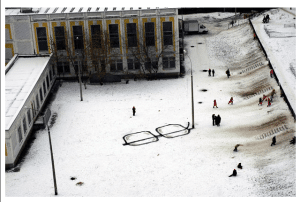

One of the artist’s more famous (and lighthearted) works is his installation that used a lightpost in creating a pair of giant, partially folded eyeglasses. The rest of the eyeglass frames were drawn in black paint extending from the post into the white snow.

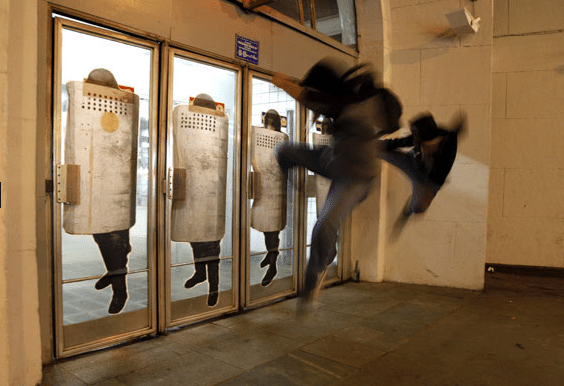

Much of his work is known for being politically charged. P183 described himself as an anarchist, and was critical of the police. In August 2011, marking the 20th anniversary of the coup of 1991 and the riots that followed, P183 created an installation where people could, in a way, fight back against police brutality. He pasted images of Russian riot police onto the entrance doors of a Moscow metro station, which intimidatingly faced would-be passengers wanting to enter the station.

A video on the artist’s YouTube account, which can be viewed here, shows policemen being ‘shoved back’ as metro-goers swing open the glass doors where the images had been pasted. P183 saw street art as a way to communicate new thoughts, political or otherwise, to the sometimes apathetic masses. In in interview with Russia Today, he said that street art is a great tool for communicating messages. “Put simply, I want to teach people in this country to tell lies from the truth,” he said. “This is what our people still cannot do.”

On April 3, 2013, a Moscow theatrical company that had recently hired P183 to create the sets for its rock opera Todd, a punk rock reimagining of Sweeney Todd, announced in a press release that P183 had died. The release gave no further details about the circumstances of his death. It did include, however, a note that the artist had recently posted a status to Facebook about his pride in his work for the show, saying, “I should note that if tomorrow I die, I can be calm that after myself I left something real.”

Andrei Molodkin – Art that Protests Through the Medium

By Kristin Torres

When asked by British art magazine Dazed and Confused what kind of emotions he hopes to stir in his audiences, Andrei Molodkin responded, “I want to start a revolution.” In the same interview, Molodkin declared bluntly, “All my work is political.”

Molodkin was born in 1966 in Bui, Russia, a small city in the Kostronoma region about 270 miles north east of Moscow. Internationally-recognized Molodkin now splits his time between Moscow and Paris. As esteemed in the art world as much as he is controversial, he’s perhaps known best for his use of seemingly unlikely forms of media – ballpoint pens and crude oil.

From 1976 to 1980, Molodkin attended the School of Visual Arts in Bui, and later attended the College of Arts in Krasnoe-on-Volga from 1981 to 1985. He eventually graduated from Moscow’s Institute in 1992, studying at the Department of Architecture and Industrial Design. In the years between 1985 and 1987, however, Molodkin detoured from his arts education while he served in the Soviet army. He still found a creative outlet, though, when he began drawing with army-issued ballpoint pens, meant to help soldiers write letters home. The ballpoint pen would later become a staple of some of Molodkin’s works. He later used the everyday instruments to create giant drawings that would become some of his most recognizable, successful, and political art installations. During this time he also came into contact with another medium that would come to define his art – oil, an element he says represents transformation, as it has both built and destroyed empires.

One of Molodkin’s military duties was served as part of a crew delivering oil cisterns (large storage tanks) in Siberia. Molodkin has said in interviews that oil both helped sustain and entertain him and many fellow soldiers, as they would rub it on their body for warmth and also eat it to get high. “We also used to smear dark rye bread with a thick layer of black oil that was used to polish boots, and dried it on the radiator. The bread absorbed light particles of oil like a sponge, and was then used by us in lieu of vodka to intoxicate ourselves on holidays or birthdays,” he told Dazed and Confused in 2011.

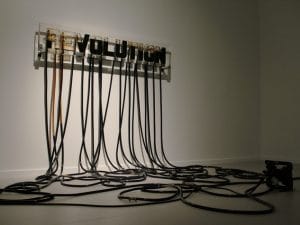

Using acrylic glass molds, Molodkin creates sculptures of key political, economic and religious words and images and fills them with crude oil pumped through plastic hoses. The oil Molodkin uses is sourced specifically from Libya, Chechnya, and Iraq, areas of no little significance in modern oil politics. In molds spelling “DEMOCRACY,” “HUMAN RIGHTS,” “9/11” and “¥€$,” Molodkin’s sculptures make a statement about three constants – life, death and politics – and the role oil plays in contemporary society and the geopolitical landscape. Informed by a life spent partially under Soviet communism and Russian and Western capitalism, Molodkin’s works represent a sense of disillusion with the prevailing regimes of 20th and 21st centuries, and comments on oil’s influence in contemporary society.

A substance that countries have shed blood over and one that sustains modern life and commerce, oil, Molodkin says, symbolizes both promise and decay. Molodkin says in an artist statement for Crude, his traveling exhibition of oil sculptures, “We lived through the communist project and watched it collapse. We then saw capitalism take over and are watching it get fiercer and fiercer as it begins to crumble from within.”

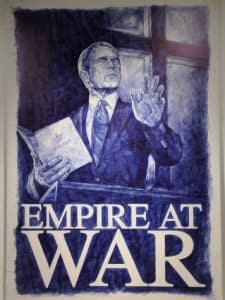

While all his pieces are nearly uniform in their political message, the media he creates them with are in stark contrast. While oil is highly sought after and can cost or accrue great amounts of money, the ballpoint pen is common and disposable. Such was Molodkin’s thought when creating 2006’s “Empire at War,” a towering twelve-by-nine foot ballpoint-pen drawing of George W. Bush at a pulpit, Bible in hand. In this piece, Molodkin used 2,764 pens to etch against a linen canvas, representing the number of soldiers who had died fighting in the Iraq war at that time. Molodkin says the method mirrored the process of war, using individuals to give all they have (in this case, their ink) and eventually be disposed of for the sake of a government’s objective. Speaking with InitiArt magazine, the artist said, “Today we trade blood for oil. We fight for it, we die for it. In millions of years, our dead bodies decompose to become oil itself.”

President Barack Obama doesn’t escape the artist’s criticism either – Molodkin also created oil-filled sculptures reading, “HOPE” and “YES WE CAN.”

That idea isn’t entirely abstract for Molodkin. In 2009, he started to try to create oil himself. He claims to have experimented with boiling down bones in a machine similar to a pressure cooker, a process he says results in an oil-like liquid – “a sweet, yellowish crude.” Never one to shy away from controversy, the artist says he performed the experiment using the remains of a dog. He also says he’s signed on human volunteers to his project, who, when they die, pledge to donate their body to art. According to Molodkin, BBC reporter Sasha Gankin was one of the first to volunteer, requesting the “oil” extracted from her remains after her death be poured into a mold of a brain. In an interview with the United Kingdom’s The Independent, Molodkin said he has also enlisted French adult film actress Chloé des Lysses, who hopes her remains will be come an oil sculpture of praying hands.

Molodkin now lives and works abroad, based in Paris, France. He continues to create provocative art, often specific to the local contexts in which he is invited to present. For instance, in Derry, Ireland in 2013 he created Catholic Blood, an installation that put the blood of local Catholics, donated to him for the purpose, into a complex shapes through an acrylic mold.

He has continued to use blood and oil heavily in his works. An exhibition entitled “Bloodline,” held in Dublin in 2020, invited viewers to donate their blood onsite and become part of an installation of works that included signs like “This Text Makes You Want To Hijack a Plane” and an image of a British passport.

A deceptive minimalism permeates Molodkin’s work, but that helps create little room for miscommunication and misunderstanding between artist and the audience. The artist says he wants his art purposefully “unmasked” and unmistakably political. “Russian contemporary art is lost in translation and that is why my art is direct.”

Voina – “War” and the Protest Art of Russia

By Taryn Jones

The radical and absurdist art collective Voina (which means “War,” in Russian) was founded in 2005 by husband and wife Oleg Vorotnikov (who goes by “Vor” or “thief” in Russian) and Natalia Sokol (who often goes by the nicknames “Kozlenok,” or “Koza,” both of which refer to goats).

Described by supporters as a “street collective of actionist artists who engage in political protest art” against “philistines, cops, [and] the regime,” the collective has also been labeled by detractors such as the Russian Investigations Committee (a law enforcement body in Russia) as a “left-wing radical anarchist collective whose central goal is to carry out PR actions directed against the authorities, and specifically against law enforcement officials with the aim of discrediting them in the eyes of the public.”

Vorotnikov is quoted as saying “the most vivid people are with us now – and not just Russians. We now have followers and members in different parts of the world” in a 2011 interview with Radio Liberty. The collective counts 3000 supporters worldwide, with 70 in Saint Petersburg alone but also with affiliations in Italy, France, South Africa, and the United States. Although the group renounces money, they did accept over $100,000 from renowned British street artist Banksy, who posted the money as bail for co-founders Vorotnikov and Leonid Nikolayev after one of the many times they have been arrested.

Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, Maria Alekhina and Yekaterina Samutsevich, the Pussy Riot members who served jail time for their role in the 2012 Punk Prayer in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, are also affiliated with Voina and have participated in several of the group’s actions. Due to their explicit and unapologetically confrontational pieces, some art circles and journalists have debated whether Voina can even be considered an artistic group, and note that it is difficult to tell when the group is acting seriously. However, co-founder Vorotnikov disregards this, noting that it is his social duty as an artist “to express openly what other people fear to express, to offend the police and thus protect the people ‘like Robin Hood.’”

Co-founder Oleg Vorotnikov was born in 1978 in Perm Krai, and graduated with a degree in philosophy from Moscow State University in 2003. As a result of his work with Voina, a warrant has been issued for his arrest, and his name is currently featured on an Interpol list. However, Vorotnikov appears to consider the warrant a compliment, calling it “one of the highest forms of recognition.” He has been charged with hooliganism, incitement of hatred against a social group (namely, the Russian police), using violence against a government representative, and insulting a government representative.

His wife, Natalia Sokol, earned a Ph.D in physics from Moscow State University in 2006, and has also been living on the fringes of society since 2010, when police seized her documents, including both her Russian internal and international passports. She was charged and made a fugitive (including the issuance of a Interpol arrest warrent) after police officers were sprayed with urine during an opposition rally in Saint Petersburg.

Other prominent Voina members include Lev Nikolayev (‘Crazy Lenya’), a college dropout who has been arrested more than 30 times in connection with his opposition action, and who is currently facing criminal charges in connection with a Voina action. Voina’s de facto spokesman, Alexei Plutser-Sarno was born in Moscow in 1962 and served with the Red Banner Northern Fleet. A graduate of Estonia’s Tartu University, he authored several books and maintains Voina’s blog, entitled “Ironic Notes from Russia About Protest Street Art and Radical Political Artists.”

Although at times Voina’s actions can appear absurd, the group maintains a list of clearly-stated goals and objectives, and believe themselves to be following in the footsteps of the radical artists from the last century. They have even gone so far as to draw comparisons with Leo Tolstoy, who, over the course of his life became increasingly ascetic, and Voina’s supporters have stated that “Tolstoy and Voina’s rabid views regarding sex, money and truth set them apart from the mainstream.” They seek to encourage the rebirth of protest art around the world, following in the footsteps of the artists of the 1920s, as well as to contribute to the rebirth of “heroical behavioral ideals of an artist-intellectual.”

Voina’s actions are often characterized by their combative and sometimes shockingly sexual nature, “designed to challenge the viewer and mock the Russian authorities.” In 2010, five members of the group painted a 60-meter tall phallus on St. Petersburg’s Liteinyi Bridge as it was set to be raised for the night. The bridge and accompanying street painting rose to stand tall above the city, and pointed towards a branch of the offices of the Federal Security Bureau. The piece was subsequently entitled “Dick Held Captive by the FSB.” The entire process took only 23 seconds, and was carefully planned and rehearsed in a parking lot over the span of two weeks prior to the action. Other members of the group acted the roles of drunk fans and confused cyclists in an effort to distract the bridge’s security guards. Russian artist Vasily Tsereteli has remarked that the group is the international leader in graffiti art, for “no artist in the world has created this kind of work on such a large scale.”

The piece was awarded the 2011 State Innovation art award, yet this apparent state sanction of the group’s work did not come without issues. Many members of the Russian art world are still wary of the state apparatus, and when asked to comment on the award later in the evening, a gallery owner declined the opportunity, stating “I have a career to think of.”

At the time of nomination to the Innovation prize, both Vorotnikov and Nikolaev were held in prison for their roles in a piece of performance art entitled A Palace Coup. The name, a play on the Russian word for “coup” or “overturning” saw members of the group overturn several police cars stationed in the vicinity of Palace Square during the course of one night in Saint Petersburg.

Voina was originally struck from the list of Innovation prize shortlistees, only to be reinstated at a later date, after leading Russian art experts Andrei Erofeev and Ekaterina Degot registered their complaints. However, Voina member Alexei Plutser-Sarno stated that the group would not accept the prize money, although they would accept the honor, as they considered the award to be “a proposal of dirty money from the Mafioso-like authorities.” Despite further protests by members of Russia’s Public Chamber, the award was eventually granted. Degot has been recorded as noting that “everybody is for Voina. It’s an unprecedented consensus in the contemporary-art community.”

The group has staged several other performance art pieces, including the 2008 “Fu** for the Heir the Little Bear!” This was an orgy staged in Moscow’s Timiryazev Museum of Biology on the eve of former President Medvedev’s election.

Another performance art example from the group is their 2010 “How to Steal a Chicken,” in which a Voina member entered a shop and proceeded to steal a chicken, by carefully concealing it in her vagina. During “How to Steal a Chicken,” other Voina members stood outside holding placards that spelled the word bezblyadno (‘without whoring’). The word is a play on the Russian bezplatno (‘free’), and was described by the group thusly: “In Ancient Russia the word ‘whore’ meant ‘lie’ and ‘deception.’ Nowadays Russia [has] millions of ‘whores’ of both sexes, who lost their moral and ethical principles; who deceive and kill each other.”

In 2008, the group orchestrated a mock public execution of several Central Asian migrant workers and members of the Russian gay and lesbian community in a major Moscow supermarket, as a way of protesting what they saw as then-mayor Luzhkov’s homophobic and xenophobic stance. The action was entitled Decemberists Commemoration, and was intended to remind the Russian public of the ideals of earlier revolutionaries.

The group states that, despite the confrontational nature of their works, in three years, not one member or onlooker has been physically harmed during their escapades. Conversely, as they enjoy pointing out, “within the mentioned period Russian cops have killed thousands of people, using their possibilities for ‘legitimate violence.’” Voina also states that they are frequently in danger due to their nature of their work, yet they remain unafraid. Natalia Sokol defiantly declared “We’ve had sex in public and are no longer scared of it. We’ve invaded a police station and are no longer scared of it. What else is there to scare us? Death we will deal with in the future. Soon we will be completely fearless.”

Russian Orthodoxy is another common target for the group. During one piece entitled “A Cop in Priest’s Robes,” Vorotnikov, dressed in the robes of an Orthodox priest and a policeman’s hat sauntered into a supermarket, where he proceeded to fill a shopping cart with food and walk out without paying, seemingly to demonstrate the shocking level of immunity enjoyed by members of both the security and religious sections of Russian society. The group states that their actions are grounded in the theory of Moscow Conceptualism, which started in the 1970s as an attempt to subvert Soviet ideology.

Perhaps part of Voina’s success is due to their disassociation from any gallery. Rather, they produce their pieces in public and post them online, free from gallery rules and making full use of the powers of democratization that the Internet presents. This is due in part to the fact that members of the group care very little for the art market, but also because they feel that their actions are international due to their innovativeness. They have joined forces with other underground art networks worldwide, and the cries of “Free Ai Weiwei!” and “Free Voina!” were heard in tandem throughout the International Art Exhibition at the Venice Biennale.

Andrei Monastyrsky, founder of the 1970s Collective Actions group is quoted as saying “if not for the Voina group, contemporary Russian art would be terrible, provincial, a commercial fu**off.” Voina has forced blatant political criticism into the arts scene, while simultaneously becoming a figurehead for freedom of expression across Russia. Russian Voina supporter and art expert Ekaterina Degot is quoted as saying “the hatred for United Russia…has reached a level comparable only to the hatred for the communists in 1988. That hatred is at boiling point, eating up people inside and – unlike 1988 – it has no constitutional expression. That hatred is Voina [.]”

Since 2011, the group has been largely inactive, save for several protests held abroad, mostly in Poland. Many of the group’s former members now live abroad. Some are now part of the Pussy Riot group. Prominant member Peter Verzilov still remains an activist with Alexei Navalny’s movement and maintains a Twitter account (which retains the handle @gruppa_voina) and an Instagram account.

You Might Also Like:

(includes current article)

Russian Protest Art that Isn’t Pussy Riot

When most think of Russian protest art today, they think immediately of Pussy Riot, the long-famous, all-female punk movement. These women have, since their “punk prayer” launched them to international notoriety, been heavily covered in the English-language press and heavily studied in English-language academia. However, Russian protest art is a diverse genre with a long […]

Gorky Park and Garage Museum of Modern Art in Mocsow

Gorky Park and Garage Museum of Modern Art in Moscow Poster Child of Russia’s Urban Revitalization Open 24/7 Free Entrance, Bring Cash for Food, Bike Rentals, etc. For several years now, Russia’s federal government and the city government of Moscow have worked together in an attempt to revitalize the capital city, with a particular focus […]

Moscow Museum of Modern Art

This MMOMA is a group of museums that house a range of contemporary artists and installations. This art is from the entire second half of the 20th century forward. Some employ traditional methods with a modern feel, and there are also exhibits that really push the boundaries of what we consider art. Some gallery space […]

10 Contemporary Russian Painters Worth a Look

Levitan, Shishkin, and Aivazovsky, among many others, are names known to every well-educated person in Russia and abroad. These artists are Russia’s pride. Today, too, there is no shortage of talented contemporary Russian painters. Their names are just not yet so widely known. AdMe.ru, a Russian site dedicated to Russian popular culture and advertising in […]

Museum, Complex: Combining Culture, Community, and Contemporary Art at Erarta

There’s a lot to be said about the highly political, oftentimes tenuous relationship between artists and art galleries throughout the Modern age. It can be argued that this ambivalent relationship has its origins at the founding of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris in 1648. For centuries, an artist’s reputation was vaulted […]

Moscow’s Modern Dance Movements

In Moscow, a close community of performers and dancers exists that examines and explore body movement. Some choreographers define their work as “modern dance,” while others call their art “nonverbal dramatic theater.” Some choreographers and dancers attempt to avoid definition all together, explaining their art more loosely with terms like “total body movement,” “improvisation,” “free […]