Tucked between modern towers and Soviet monuments of Bishkek’s downtown area stands a small, gated house. A plaque outside humbly identifies it as the Memorial House Museum of O.M. Manuilova.

Olga Maksimilianovna Manuilova was born in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia in 1893 and educated as a sculptor in Moscow. The daughter of a military doctor, her family was eventually transferred to Central Asia where her work became highly influenced by the local cultures. The memorial house museum is where she lived from 1948 until 1984, winning strong local acclaim for her work. The building became a government-sponsored museum in 2000.

The house museum itself is quite small and free of charge to visit. It is open only on weekdays from nine until five, with an hour for lunch between 12 and 1 pm. It can be somewhat hard to find as the grounds of the museum are overgrown with small bushes and flowers. A large over-hanging tree blocks a direct view to the house from the street, making it seemingly disappear from the passerby.

However, upon entering the museum, the visitor is presented with a small hall holding a large stone bust of Manuilova at the end, next to a handmade donation box. The museum has just five rooms, one in the back which acts as an office and another that was behind a locked door.

The initial hall is flanked by family photos, photo albums, and even infant clothes that belonged to Manuilova. Photos include those showing her with her family as a child, on summer excursions, and her time in Moscow. Throughout the building are photos of Manuilova working on her statues and art in the very same house in which the museum located, as well pictures showing the erecting and unveiling of many of her statues located throughout the city.

The photos and artifacts throughout the front two rooms create a biography of Manuilova, with descriptions written in Kyrgyz and Russian. The biography follows her entire life, starting with her birth until her university studies in the entrance hall. It continues into another room, tracking her early career, move to Kyrgyzstan, and her life as a leading sculptor. It focuses on her accomplishments as a dedicated Soviet artist who had come to love the culture of Kyrgyzstan and Central Asia as whole. You can feel the admiration the Kyrgyz feel for Manuilova, as a foreign Russian arrival who helped show the life and beauty of the nomadic people’s culture to the USSR and beyond. She was awarded various honors, including the Order of the Red Banner of Labor, People’s Artist of the Kyrgyz SSR, and even has an asteroid belt named after her.

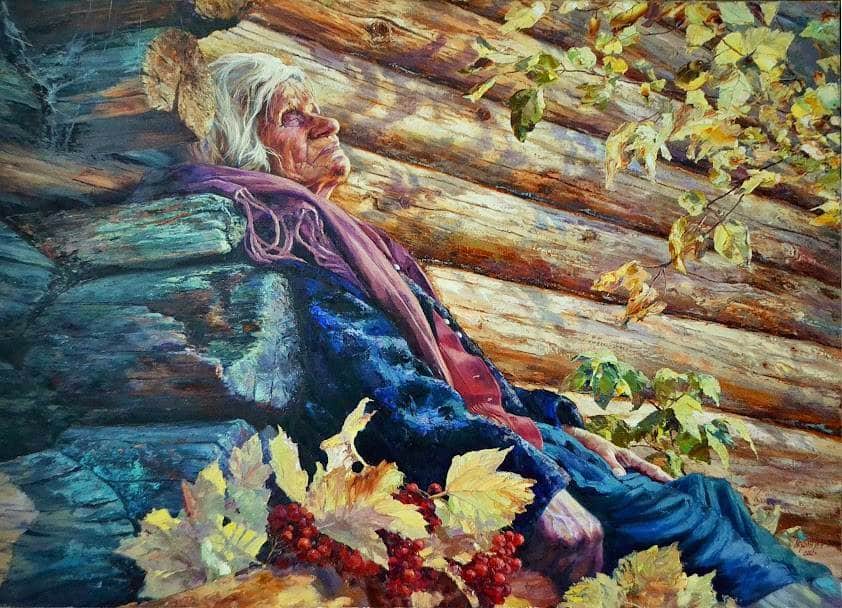

Some of her smaller statues sit behind glass cases in these two rooms, depicting traditional Kyrgyz culture, clothing, lifestyle, and beauty. She also has works showing Uzbek, Kazakh, as well as Tajik culture. Small marble Kyrgyz women hold infants at their hip and seemingly gaze over the Central Steppe. A young farmer holds a water vase over his head, bringing it back to the fields. Depictions of heroic Kyrgyz warriors (batyrs) stand next to their horses. Statues of traditionally-bearded Kyrgyz men playing the two-stringed kyl kiak stand in contrast with her (then) modern depictions of a soviet Kyrgyz woman heading to a factory. She was able to capture the span of Central Asian history from its nomadic roots to industrial transformation at the hands of the Soviets.

The final room that is open to the public is twice as large as the others and holds a large collection of paintings, drawings, busts, statues, and other artwork. Life-size busts of old Kyrgyz men wearing turbans take up the floor space on the edges of the room. An interesting bust includes that of Gen. Panfilov, a famous Soviet commander that led the defense of Moscow with a contingent of Kyrgyz soldiers, who Manuilova would commemorate with a large statue in Panfilov Park in Bishkek. A painted portrait of an older Manuilova hangs on the wall. It is one of the few things in the museum that has any color, most other works being of plain wood, stone, or bronze.

A small, unplugged television sits on a table as the only form of multimedia in the whole museum. Brochures lay on the table as well, one showing all Manuilova’s works, another compiling the biographical texts used throughout the museum, and the last being a pamphlet about Manuilova and the museum. All brochures are in Russian and Kyrgyz. An English guidebook of memorial houses in Bishkek can be bought at the Ishak Razzakov Museum for 100 som (~$1.25). This book includes an English description of Manuilova’s life, work, and information about the museum.

A Kyrgyz babushka acts and greeter, cleaner, usher, guide, security guard, and manager. Her information about the museum, however, is limited to what is written in the pamphlets and on the walls. She offers to show photos or statues that you may have missed. The babushka’s passion for the artist and her work goes beyond her simple understanding of the art and history, as it is apparent with her excited calls to come look at photos already passed or invitations to sit and look at the brochures. She explains in Russian that the largest room was the workspace where most of the artwork, seen in photos and in the museum, were created.

She goes into the office and comes back with a key to the locked door. She opens the door to reveal Manuilova’s bedroom that now acts as the museum storage. The bedroom/storeroom is filled with dozens of small statues and more artwork. Shelves are filled with figures of Kyrgyz men next to their horses, large stoic Soviet busts, girls holding vases, animals, mythological creatures, and farmers holding their harvest over their heads. There are paintings leaned against every wall, hiding their artwork with their backs facing towards you. The simple blue wooden table that now seems to hold junk mail and other paperwork was the worktable of Manuilova, where she would draw, plan, and sculpt some of her smaller works. Her old clock sits on top of one of the shelves across the room in between the small statues as if it was a work of hers as well.

The museum focuses solely on Manuilova’s life, achievements, and her work. It highlights her contributions to Kyrgyz culture, by giving the traditional local styles and life a permanent place in the world with her stylistic and detailed statues. It does its best to give a history who she was and provide details about her life. The biography in the museum is extensive and the pamphlets provide much information as well. Yet it can only go so far, as much of the information is not available in English, and even searching for information about her in English on the Internet brings few results.

The museum does not mention or focus on any of the historical events that affected her life besides a brief mentioning of the Second World War. It makes her life appear to be in a vacuum of history as perhaps might have been presented by a soviet-era censor. Thus, her actual artwork is the main highlight of the museum for any visitor.

The museum felt personal and cozy, yet aged and forgotten. The home is well maintained but outdated and without any modern amenities. Its natural lighting, small size, and old architecture contribute to the feeling of stepping back in time, despite being mere blocks from the main shopping square in Bishkek. It is a humble love letter to Manuilova that can be enjoyed despite its faults.

You Might Also Like

Museums as Self-Care

In 2018, doctors in Montreal began prescribing visits to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) for patients experiencing depression, anxiety, and other health issues. This innovative approach to mental health treatment was launched under the initiative of the MMFA in collaboration with Médecins francophones du Canada (MFdC). The program allows physicians to provide patients […]

Guide to Bishkek’s Top Museums for Students

The Kyrgyz were largely a nomadic civilization up until the 20th century. The city of Bishkek has a number of museums documenting this fascinating history as well as the development of the arts and sciences in Kyrgyzstan. These museums were mostly established during (and today are often unchanged from) Soviet times, including a number of […]

The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts in Bishkek

The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts in Bishkek showcases native art forms as well as painting, sculpture, and other works, highlighting those created by Kyrgyz artists. The museum is centrally located and is perfect for a day trip with an abundance of restaurants and cafes nearby. The article below will tell the history of […]

The National Historical Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic

The National Historical Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic is a great place to get started when visiting Kyrgyzstan. The museum’s extensive collection of more than 90,000 exhibits includes artifacts from Kyrgyzstan’s prehistory, from its ancient Silk Road era, Soviet-era history, and modern state. Culture exhibits focus on Kyrgyz nomadic culture, traditional handicrafts, and the musical […]

The Evolution of Art and Painting in Central Asia

While Central Asia has a long, rich history, the modern nations of the region are a direct result of 20th century colonization. Prior to Soviet interference, the many ethnic groups and distinct societies of the region were loosely grouped under the geographic term of Turkestan. Under Soviet control, the region was divided into the Turkmen […]