The Memorial House of Iskhak Razzakov opened on December 20, 2005. The house served as the home for the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Kirghizia (Kyrgyzstan) throughout the span of the Soviet Union. Iskhak Razzakov lived in the home with his two children and wife during his tenure as First Secretary from 1950-1961.

The museum was established by the Kyrgyz government and is maintained largely through government funding.

Razzakov is remembered in Kyrgyzstan as a leader who built many educational and cultural institutions in Kyrgyzstan and worked hard to improve the economy and quality of life there. He also generally worked to promote Kyrgyz identity. Initially working with Khrushchev’s blessing, he eventually fell out of favor and removed from his post. He is often held up as a model leader who fought for what was right even when it eventually cost him everything. That said, the museum does shy away from what can be considered the darker sides of history that occurred during his time in office.

The home sits far away from the center of Bishkek, tucked away on a side road around other similar looking houses and buildings. The only hint of its bureaucratic history is a guard house next to the iron gate entrance. Still very well taken care of, the house has new paint, a well-manicured flowerbed, and a small, immaculate lawn. A large driveway leads to the heavy wooden entrance door, which sports a QR code which, once scanned, gives a brief description of the museum in Russian and Kyrgyz. The house has only a few windows, all with thick iron bars protecting them.

The house museum is free to enter and has nine different rooms including an entrance, main hall, and enclosed veranda. Two women working the museum stand on guard at the entrance. Their excitement for visitors is visible as they begin almost immediately leading you on a tour of the entire museum. Apparently guests are not extremely frequent. They begin by pointing out the books in the entrance that were either written by Razzakov or were read by him as some of his favorites.

I was offered a book, Guide of the House Museums of Bishkek for 100 som, which has information about the Razzakov museum and others. Once accepted, the guides asked to take a photo of me holding the guidebook with a photo of Razzakov in the background. The women then guided me to the room off to the right. In the center stands a model of traditional Kyrgyz yurt. The guide begins by explaining the early life of Razzakov in Southern Kyrgyzstan, emphasizing that the population of pre-Soviet Kyrgyzstan was quite poor. Most lived off the land by herding and raising livestock, including Razzakov’s family. By the time he was nine, both of his parents had died. He was sent to an orphanage in Khujand (then Uzbekistan, now Tajikistan).

It should be noted that there are some discrepancies in various histories of Razzakov’s childhood. None list causes of death for his parents. Some say that his father died when he was just five, other sources say nine or ten. Some refer to his father, at least at the time of his death, as being a miner.

The guide next took me anti-clockwise in the museum to the next room, which holds many photos and items from Razzakov’s time in school. Many class photos and photos of Khujand are on the wall. There are class notes, report cards, letters, and some toys of his behind glass. The guides explained every photo and object in detail, knowing exact dates and locations. They told me how Razzakov went to university in Moscow, showing me photos and notebooks from his studies. They explained how the bounty of photos and objects were donated from his still-living daughter in Moscow.

The next room shows the start of Razzakov’s political career. It began in 1936 and expanded during the Second World War he was promoted to the State Planning Committee Representative for the Uzbek SSR and eventually became Secretary of the Communist Party’s Central Committee of Uzbekistan. He was then appointed as Chairman of the Public Commissars Council of the Kyrgyz SSR and later as the First Secretary of Kirghizia, the highest position in the Kyrgyz Republic.

His time as First Secretary brought great change and rapid industrialization. The Second World War had brought some factories and industries to Kyrgyzstan, but the republic was still predominantly rural. Razzakov gained immense funding to bring large projects that brought dams, factories, mines, bridges, monuments, schools, universities, theaters, more organized farming methods, trains, and public transport to Kyrgyzstan.

The room devoted to these years is filled with photos of Razzakov shaking hands with fellow Soviet Secretaries, standing over a newly dedicated bridge, digging coal with workers, overseeing factory constructions, and smiling with school children. His clothes, honors, certificates, briefcase, and more lay behind thick glass in perfect condition. The photos clearly show the leader in the best light possible. The pristine smiles and the happy workers in the fields and construction sites seem perhaps too good to be true. After all, if he was so unanimously revered, why are there thick bars on all the windows of his house? The guides, however, show only the photographs and revere the man, considering him the best leader the nation has had for all he did for the people of Kyrgyzstan. The guides’ genuine zealousness is easy to feel but determining where exactly the man stops and the myth begins is a point that presents itself as an obvious focal point by this time in the tour.

We continued onto the enclosed veranda. A very large statue of Razzakov stands in the center of the half-circle room. Small exhibits show more photos of Razzakov with Premiere Khrushchev, attending meetings in Moscow, enjoying ballets in Bishkek, and more factory openings. Children, the guides say, would come to the veranda and perform patriotic and traditional songs for the First Secretary and his family.

The next two rooms continue Razzakov’s time as First Secretary. There are some photos of him with his family showing what the house-museum looked like when it was lived in. Many other photos are actually duplicates that were already posted in the earlier rooms. The guides still continued to explain every photo, despite having done it before, adding to the growing oddity of the situation.

The final room we viewed was his study and still has his desk with various stamps, letters, pens, and a large lamp. The guides passionately explain the history of the desk and point out the wall behind it, holding all of the same books he read and kept in his study including works from Aitmatov, Pushkin, and Gogol. There are encyclopedias, Das Kapital, the Communist Manifesto, and other political books.

The main hall, which allows passage to all the other rooms, served as the living room and dining room. Paintings of Issyk Kul hang on the wall, a piano and a large leather couch all stand exactly where they did when Razzakov claimed this residence. Photos in the museum show parties and gatherings of officials in the very same room. Now there are rows of foldable chairs in the middle of the room for school groups that come once a month.

The presentation of the museum begins well-researched and detailed, but ends muddled and vague, as there are actually too many rooms for how many photos and artifacts have been made available. The information presented is presumably accurate, but shown in an extremely biased manner that ignores anything but gleaming achievements.

And there were, of course, problems at that time. Although the country was industrializing and modernizing, many resented the loss of their herds and traditional way of life. The Gulag system, although winding down at that time, was still active. Censorship remained an issue throughout the soviet era, including at the theaters that Razzakov is shown attending. Thus, while the museum is interesting and worth a look, it raises at least as many questions as it answers.

The museum is completely in Russian and Kyrgyz and the guides were not able to speak any English either. The only English can be found in the precious Memorial Houses in Bishkek Guidebook. If you can get past the language barrier, then the guides are extremely knowledgeable about Razzakov and his accomplishments. While Razzakov remains genuinely popular in Kyrgyzstan – among both conservative and liberal Kyrgyz – a discerning mind should come away from the museum wanting to dig deeper into history than the museum does.

You Might Also Like

Museums as Self-Care

In 2018, doctors in Montreal began prescribing visits to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) for patients experiencing depression, anxiety, and other health issues. This innovative approach to mental health treatment was launched under the initiative of the MMFA in collaboration with Médecins francophones du Canada (MFdC). The program allows physicians to provide patients […]

Guide to Bishkek’s Top Museums for Students

The Kyrgyz were largely a nomadic civilization up until the 20th century. The city of Bishkek has a number of museums documenting this fascinating history as well as the development of the arts and sciences in Kyrgyzstan. These museums were mostly established during (and today are often unchanged from) Soviet times, including a number of […]

The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts in Bishkek

The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts in Bishkek showcases native art forms as well as painting, sculpture, and other works, highlighting those created by Kyrgyz artists. The museum is centrally located and is perfect for a day trip with an abundance of restaurants and cafes nearby. The article below will tell the history of […]

The National Historical Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic

The National Historical Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic is a great place to get started when visiting Kyrgyzstan. The museum’s extensive collection of more than 90,000 exhibits includes artifacts from Kyrgyzstan’s prehistory, from its ancient Silk Road era, Soviet-era history, and modern state. Culture exhibits focus on Kyrgyz nomadic culture, traditional handicrafts, and the musical […]

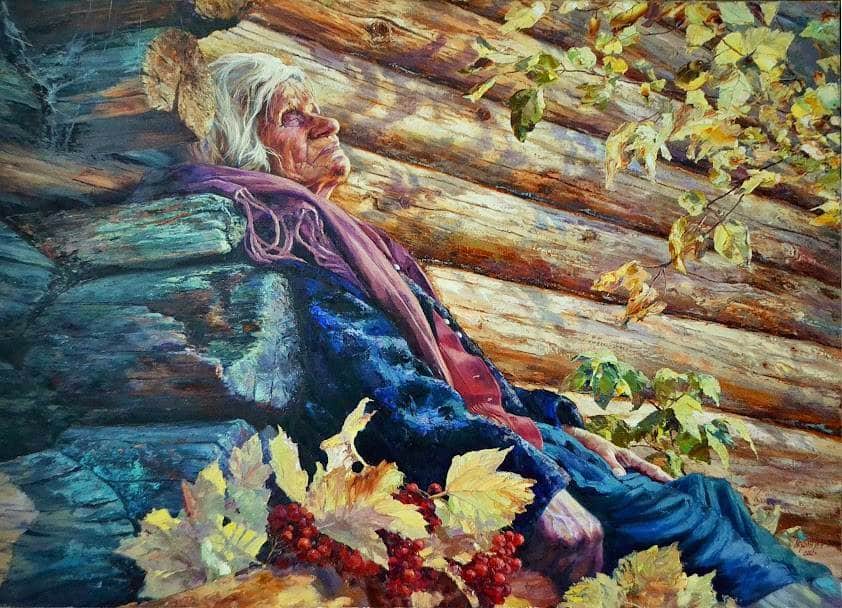

The Evolution of Art and Painting in Central Asia

While Central Asia has a long, rich history, the modern nations of the region are a direct result of 20th century colonization. Prior to Soviet interference, the many ethnic groups and distinct societies of the region were loosely grouped under the geographic term of Turkestan. Under Soviet control, the region was divided into the Turkmen […]