The Alexander Pushkin Museum and Memorial Apartment in St. Petersburg, Russia, makes, appropriately, a very strong use of narrative. The museum builds the story of Pushkin, his life and writing, all while maintaining a tight focus on the end of his story – a tragic death that, it seems, has never stopped being mourned.

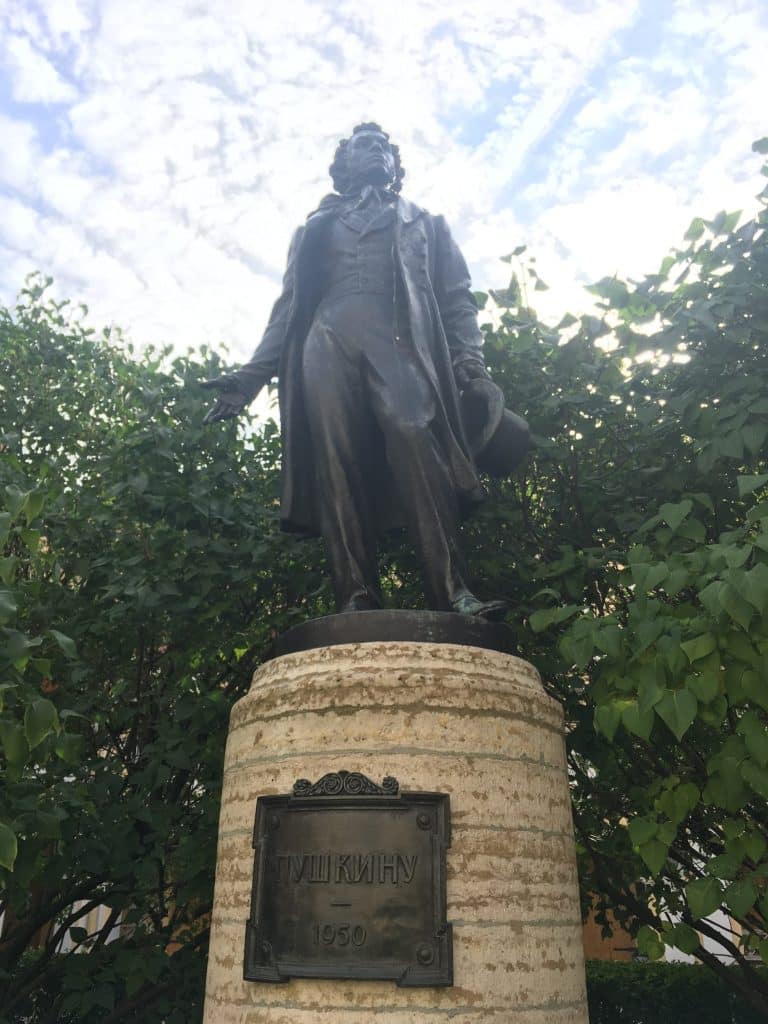

The museum is a short walking distance from the Hermitage. Like the other Western European buildings around it, the exterior of Pushkin’s former home is well kept along the Moika River. Its façade is painted a bright yellow and the courtyard’s gardens are freshly tended. The setting also introduces us to the main character with a large statue of Pushkin at its center, its height and confident stance seemingly symbolizing Pushkin’s social and literary prestige.

Inside, Russian-speaking guides are available as are audio guides in Russian, English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Finnish, and Chinese. These diverse translations indicate not only the international popularity of the museum, but also its healthy state support as an important monument in St Petersburg’s cultural history and modern identity. High quality audio translations are generally not cheap, but are widely available in assortment here.

The staff will greatly encourage you to take a guide, the need for which is apparent after you enter: there are no signs to tell you about the different exhibits. The museum is thus structured to discourage you from reading encyclopedic entries from Pushkin’s life, and instead almost forces you to drift through a full narrative the museum tells through its own setting.

To many Pushkin is considered the “Father of Russian Literature,” for his great contributions of poetry, short stories, and novels to what was then a fairly small literary canon. Pushkin’s particular use of language, and his dark tone, marked the beginning of the Russian literary canon as it is known today.

The beginning of the audio guided tour in English similarly establishes a darkened mood by first introducing Pushkin’s death. Slow, sometimes melancholic classical music plays in the background from this start and through the entire tour, joining it together with a single soundtrack. It was in this apartment, the guide says, that, on February 10, 1837, Pushkin died after being fatally wounded by J. Dantes in a duel. The first exhibit shown is a painting of Pushkin lying on the snow, gripping his wound, after being shot. With this opening of its tale, the museum establishes itself as a historical one dedicated to depicting the final year of Pushkin’s life, what occupied thoughts, and his family. The museum, thus, stands as a place where one pays their respects to the author, by educating themselves on his final days and supporting the continuance of his story.

The audio guide then delves into Pushkin’s relationship with St Petersburg. Although Pushkin was originally born in Moscow, he and his wife spent much of their time mingling in St Petersburg’s high society. It was not until 1836, however, shortly before his death, that Pushkin and his family settled into the eleven room apartment where the museum is now based. Thus, his final days in St Petersburg, the city that inspired much of his literature, forever link him to the city’s literary culture.

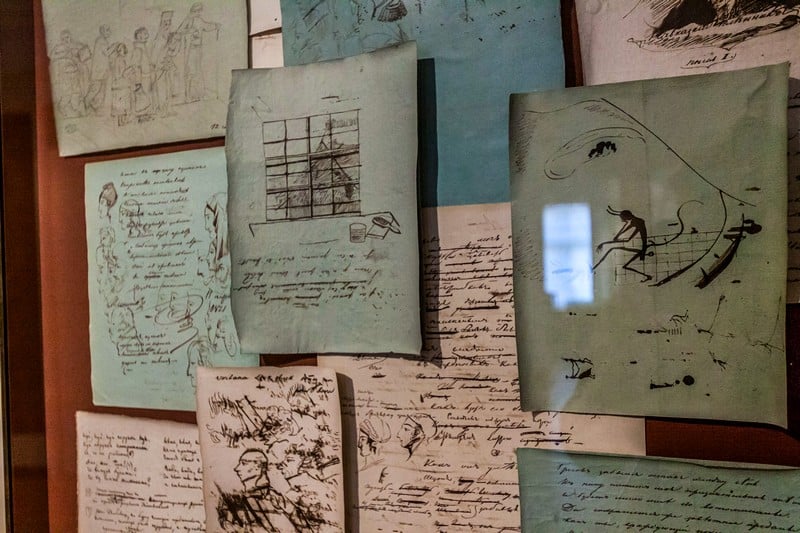

The guide and museum then move on to a display of pages from Pushkin’s original manuscripts, obviously chosen because they are covered in his own hand-drawn illustrations. These not only reference his great works early on, but calls attention to his originality, humor, and to his personal creative style. This builds the character of Pushkin into a more relatable, more human protagonist.

The next display delves into the tragic circumstances surrounding Pushkin’s death. A set of revolvers are set amid angry notes written between Pushkin and J. Dantes. The audio guide explains that after Dantes arrived in Russia from France, he actively pursued Pushkin’s wife Natalia. This resulted in widespread rumors that Natalia was having an affair with Dantes. To high society’s surprise, however, Dantes eventually married Natalia’s older sister Ekaterina, but this apparently did not stop his inappropriate behaviour towards Natalia. In response, Pushkin wrote Dantes a “highly insulting letter” which he knew could only result in a duel. This duel took place on January 27, 1937. It was then that Pushkin received a fatal shot to his abdomen that caused his death two days later.

Proceeding up the stairs to see the living quarters of the apartment, one is greeted by a white door with Pushkin’s name handwritten in pencil. This was written by a friend of Pushkin’s and had acted as a poster-board to inform the public of Pushkin’s deteriorating condition. Below this are two notes that describe Pushkin’s weak condition before his death.

Natalia’s boudoir is welcoming, lavishly decorated with wooden furniture and burgundy curtains. However, the audio guide once again uses this to remind the visitor of the narrative’s sad end. A sofa pulled next to a door leading to Pushkin’s study, we are told, was moved there by Natalia who wished to be close to her husband in his final moments. From there, she would hear his cries of pain, without being able to help him.

The family room of the apartment is intimate. Toys on display seemingly invite play. The room is decorated in the Russian style, the toys were purchased from a small Russian market, and the all the furniture and paintings are original to the time period. Pushkin’s pride in his family can be seen in the paintings he commissioned of his children. The audio guide states that, in his final weeks, Pushkin had written to a friend of his growing family, saying “I now have no reason to be sad.” This joyful sentiment is also melancholic, as it too helps foreshadow the untimeliness of Pushkin’s eminent death.

Pushkin’s study is elaborately decorated with books, a sofa for relaxing while reading, and a desk used by the author. On this desk are pages from his original letters and manuscripts as well as a small decorative statue of an African boy that was given to Pushkin by one of his friends to honor Pushkin’s African heritage. The guide informs that, after the duel, Pushkin was brought to the sofa on display, where he spent his final days. In this room, Pushkin passed away, surrounded by his friends, declaring “my life is over.” Although there are no clear blood stains on the sofa, in recent years, the guide says that technology has linked blood found on the sofa to Pushkin.

The final room is a small parlour where Pushkin’s wake was held. On the wall is a painting of Pushkin in his casket and his death mask – a plaster of Paris mold that was often taken after death of important people at this time. The room’s minimal decoration makes you feel as though you are paying respects to the author, like those who attended Pushkin’s visitation in 1837. There is almost nothing else to focus on in the room, save the late author’s implied remains. We are left where we began in the museum’s narrative: at the end.

Exiting the museum and returning again to the tended gardens of the courtyard and the looming statue honoring Pushkin’s legacy, however, we are taken to a prologue of sorts. We are reminded of St Petersburg’s vibrant literary life and the beauty of the city and Pushkin’s works have served as inspiration for such major Russian authors such as Dostoyevsky, Gogol, Chekhov, and even authors today. Pushkin’s literature, as well as his life and death, make him a vital part of St Petersburg’s cultural history. The house museum aptly depicts the tragedy of the beloved author’s untimely death, the sadness that surrounded the end of that life cut short, while reminding us of the greatness of the man who lived it.

The Alexander Pushkin Museum and Memorial Apartment

12 Naberezhnaya Reki Moyki

Hours: Wednesday to Monday, 10:30 am to 6pm. Last admission at 5pm.

Admission: Adult 150 RUB. Students with valid ID 60 Rubles. Children under 16 free. Audio guide available for 190 RUB.