There is always history surrounding us. In a city like Moscow, this can seem overwhelmingly apparent. Moscow has many imposing buildings from many eras – some are immediately recognizable and others only invite wonder as to what stories lay behind their beauty or grime.

Lubyanka is the name commonly used to refer to the building that has historically housed the security services of the USSR and modern Russia, from the Cheka to the KGB to the FSB. The name has also, for a much longer history, been applied to the adjacent square and surounding neighborhood.

The Lubyanka Building

by Alyssa Rider

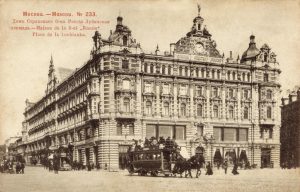

The building now known as Lubyanka was originally several buildings.

The two largest were originally designed by Alexander Ivanov and were separated by a street. The largest of these two was built in 1898 and the smaller in 1902 by the All-Russia Insurance Company. Insurance and banking were rapidly growing and profitable industries at that time. Insurance companies would often invest their substantial cash holdings in real estate. Thus, most of the buildings were built as residential and the space was rented for profit.

Perhaps ironically, the original, much more ornate façade of the main building included two female figures representing Justice and Solace.

The buildings were seized following the 1917 revolution and became the headquarters for the secret police – the Cheka at the time, though it has served in the same role for the various iterations of the Soviet, and now Russian, state security services – from the OGPU and NKVD, the KGB, and now the FSB.

Lubyanka prison was established in 1920 inside a two story structure adjacent to the main buildings. It had originally been a hotel built, again, by the All-Russia Insurance Company. It was soon expanded to six floors. Jokes referred to it as the “tallest building in Moscow,” as one could purportedly see Siberia (and the Gulag system) from its basement, as that was the fate that awaited most that saw the inside of the prison’s walls.

In 1940, Aleksey Shchusev was commissioned to enlarge the complex to accommodate the increasing amount of staff required to handle the Great Purge. The staff had grown from 2,500 in 1928 to nearly 34,000 in 1940.

An extra floor was added, and the main building expanded horizontally, consuming and incorporating nearby buildings. This expansion was interrupted by the Nazi invasion, leaving the facade lopsided until it was completed under the orders of Yuri Andropov in the 1980s.

The building now contains FSB headquarters, a group of holding cells, the headquarters of the Border Guard Service, and two museums: one devoted to the KGB/FSB and one dedicated to the old prison (neither is actually open to the public).

The Museums Inside the Lubyanka Building

The museums offer regularly updated exhibits, both historical and modern. The Museum of the KGB, now known as the Historical Demonstration Hall of the FSB of Russia, is located inside the Lubyanka complex, and contains four rooms and over two thousand exhibits.

Exhibits cover the history of Russian and Soviet counterintelligence, and there are documents from the times of both Peter and Catherine the Great, as well as the Napoleonic War and WWI. There are separate stands with information on events relating to mass repressions, as well as a room dedicated to WWII. The museum also includes a significant amount of technical equipment that has been used for reconnaissance and counterintelligence purposes, as well as more recent documents relating to FSB operations.

The prison museum has never been open to the public and is maintained only for FSB personnel and high-ranking government officials. The “Demonstration Hall” was opened to the public in 1989. Accessing it was still difficult, as it is located inside the FSB complex and tours were offered almost exclusively through private tour companies and only after screening potential visitors. In recent years, the tours became rarer and today this museum, too, is officially closed to outside visitors.

The History of Lubyanka Square

By Alyssa Rider

The building is not the only part of Lubyanka with a history. The square outside, also known as Lubyanka (Лубянская площадь in Russian), has gone through some changes as well, in both name and appearance. While it began as a small, circular island creating a traffic roundabout, it has since grown into a two-part park.

Where Does the Name “Lubyanka” Come From?

The name originally came from a district of Veliky Novgorod – Lubyanitsa – after a group of Novgorodians came to settle that district of Moscow. The first mention of this name comes from 1480. The word comes from the Russian “луб” (“lub”) which refers to both plant fibers suitable for weaving as well as removed tree bark. Novgorod was known for both textiles and multiple uses of tree bark, including for shoes and paper. Thus, it’s likely that these settlers were craftsmen specializing in the use of “lub.”

Later, in the early 19th century, the square came to be called Nikolskaya, after the nearby Nikolsky Gates, which once connected Lubanka Square with the walled city district of Kitai Gorod.

The name of the square changed once again in 1926, becoming Dzerzhinsky Square, in honor of Felix Dzerzhinsky, the founder of the Cheka, who died that year. The original name, Lubyanka (Лубянская площадь in Russian), was reinstated in 1990.

Lubyanka: Fountain, Statue, or Abstract Nothing?

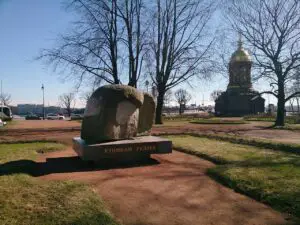

The names were not the only thing that changed. In 1835, a fountain was installed on the square. This fountain was called Nikolsky Fountain (its name borrowed from the same gates mentioned above), and was designed by the Italian sculptor Giovanni Vitali and supplied potable water to the neighborhood.

Nikolsky Fountain is one of the oldest in Moscow, and it still stands, but no longer on Lubyanka. It was moved in the 1930s to a new location in the courtyard of Alexandrinsky Palace in Neskuchny Garden, part of the Gorky Park complex in central Moscow.

In 1958, a 15-ton iron statue of Dzerzhinsky, known as “Iron Felix” was installed in its former place on Lubyanka. This statue, in turn, was toppled in a public demonstration after the fall of the Soviet Union. It was transferred by the Russian Academy of Arts to the Muzeon, also known as Fallen Monument Park, to be joined by many other Soviet statues removed or toppled at that time.

In 2017, a general renovation of Lubyanka and the surrounding traffic patterns was announced by the city. It was debated if the fountain or even Iron Felix should be brought back. In the end, however, the space was enlarged and landscaped with flat, circular geometric shapes. The space, used and undecorated, remains largely unused.

In 2021, another effort to bring back the statue was proposed by the modern Communist Party in Moscow. The mayor initially agreed to allow the issue to be voted on in a referendum, but soon reversed his decision and killed the initiative.

The Solovetsky Stone

By Alyssa Rider

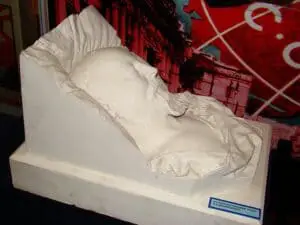

The Solovetsky Stone is a monument located across the street from Lubyanka Square in a separated area known as Musuem Park. It was created in commemoration of the political prisoners who were repressed under the GULAG system.

The Solovetsky Stone is a large granite block brought from the Solovetsky Islands, where the Solovetsky Special Purpose Camp operated in the 1920s and 1930s as part of the GULAG system. It was officially opened on October 30, 1990.

Founding such a memorial had become a matter of public discussion a few years earlier, in the late 1980s. The Memorial Society, now a globally-respected NGO, began a petition with the goal of creating a monument of political repression in 1987, and in 1988, a Public Council for the creation of such a monument was formed. A contest was also held in 1988, wherein people could submit their monument ideas and suggest locations, but a winner for this contest was never chosen.

The specific stone idea came from a memorial created in the village of Solovetsky in 1989 by former Solovetsky prisoners, many of whom stayed there after their release, and members of the Memorial Society. Members of the Society from Arkhangelsk, St. Petersburg, and Moscow liked the idea so much that they acquired boulders to place in their own cities.

The opening of the Moscow memorial on served as a triumph not only in its own right, but also marked the first official recognition of the Day of Victims of Political Repression since that day began to be recognized by dissidents in 1974. Every year on this day, people now gather near the Solovetsky Stone to mourn. Since 2007, a practice called the ‘Return of Names’ has taken place on the 29th from 10 AM to 10 PM – people from across the city gather in a long line to take turns reading the names of Muscovites who were executed. Similar actions take place in many other cities and even other countries, on this day or the next.

The Solovetsky Stone has also become an unofficial site for civil protest, serving not only as a memorial but as a symbol for modern-day political dissonance.

Touring Today’s Lubyanka Square and Surrounding Area

By Katherine Weaver (Spring, 2018)

The stories of Moscow’s Lubyanka District were recently opened for me through a guided walking tour by Bridge to Moscow, a Russian company that specializes in unique English-language tours. The tour centered on the well-known Lubyanka, but also discussed other structures in the same neighborhood that spoke to the same history. A visit to the GULAG History State Museum finished the day off with a multimedia experience concerning the history that played out, in part, inside those storied buildings.

The Lubyanka, perhaps the most infamous building in Russia, was originally established in 1898 as the All-Russia Insurance Company’s headquarters. It was then nationalized following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 and converted to house the Cheka, the Soviet Union’s secret police. Although the Cheka transitioned to NKVD, KGB, and later FSB, the headquarters always remained the same.

The GULAG system, run by the secret police, rapidly expanded during the Great Purge of 1937-38. Hundreds of thousands of Soviet citizens were arrested, sentenced for “counterrevolutionary activities” under Article 58 of the USSR’s Criminal Codes, and sent to the GULAG system that spread across the USSR. Tens of thousands of others were executed before ever leaving Moscow. The Lubyanka became the USSR’s most infamous GULAG processing station. It earned its nickname as the “tallest building in Moscow” during this period, because as they said, Siberia (a euphemism for GULAG) could be seen from the basement.

An expansion of the Lubyanka began in 1940 to accommodate additional prisoners and personnel. An additional story was added vertically and the building was expanded horizontally and absorbed buildings behind it. A grey and dreary apartment building was constructed directly behind the growing building for secret police officers. Only the right portion of the building was completed before the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in 1941 – the rest was completed under Yuri Andropov in 1983.

Although the prison is said to be in the basement, some claim it was actually on the windowless top floor. Most prisoners were brought in in the dead of night and led blindfolded through long, convoluted paths to intentionally disorient them. Their “walk time,” which came at random intervals, was held on the roof. Over time, the Lubyanka became a symbol of the Soviet state security organs and political repression. To this day, Lubyanka still houses the Lubyanka prison, now a museum.

A Museum of the KGB (now the Historical Demonstration Hall of the Russian FSB) was opened in 1989. Unfortunately, although the facility still exists, it is not open to the general public (as it is within a highly secure building), and entry is only granted to those with special permits, which are apparently difficult to get. We did not get to go inside.

Interestingly, the first known mention of name “Lubyanka” for this Moscow neighborhood comes from 1490, when Grand Prince Ivan III conquered Novgorod and settled many of its residents in this area of Moscow. The Novgorodians called the area Lubyanka after the Lubyankskiy District in their native city. Just 900 meters northeast of the Kremlin, Lubyanka Square has long been a nucleus of life in Moscow.

Lubyanka Square was renamed Dzerzhinsky Square from 1926-1990 in honor of the founder of the Soviet security service, Felix Dzerzhinsky. A statue in his honor was erected in 1958, but following a failed coup against Mikhail Gorbachev in 1991, the statue was pulled down by protestors and removed from the square (but preserved in Muzeon, a statue complex across the street from Gorky Park in Central Moscow). In 1991, the square’s original name, Lubyanka Square, was restored.

A three-minute walk towards the Kremlin will bring you to 23 Nikolskaya Ulitsa, the Shooting House (Никольская улица, 23 – Расстрельный дом). The building earned its name between 1935-50, when the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR oversaw investigations of counterrevolutionary terrorists there. Cases were heard on the third floor without participation of the parties involved, appeal was forbidden and capital punishment carried out immediately, all in the same building. More than 30 thousand people, including military officers, engineers, writers, artists, and other Soviet citizens were sentenced in the Shooting House

After the collapse of the USSR, the building was taken into private ownership and is now unmarked and hidden behind construction mesh. It is slated to reopen as a shopping mall “within the next few years” – but its been officially under reconstruction for more than a couple of decades now. Directly across from the Shooting House, a new-age restaurant proudly displays cured meat in the window.

On October 30, 1991, an organization called Memorial, erected the Solovetsky Stone on Lubyanka Square to honor those that had been killed by political oppressions. At the time, they were also pushing for the state legislature to mark a Day of Political Prisoners of the USSR on the Russian calendar. In 1992, October 29th was officially set aside The Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Political Repressions. The new non-state holiday is not a day off and, perhaps most interestingly, leaves out “USSR” from its name.

Since 2007, in an event known as “The Return of the Names,” the name, age, profession, and date of execution of those shot in Moscow during the Great Terror are read one after another by Memorial-organized volunteers from ten in the morning until ten at night at the Solovetsky Stone every October 29th. The Return of the Names has yet to reach the middle of the list.

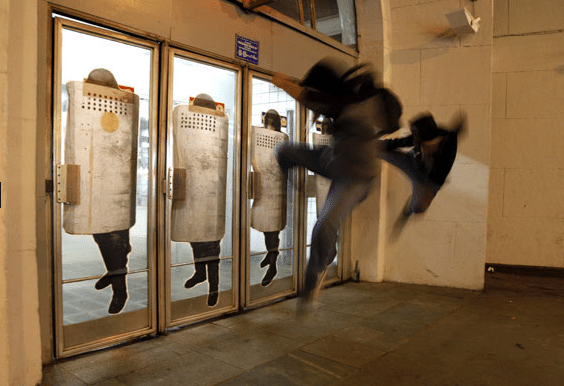

Although our group tried to see the stone, the area is currently under construction. When our guide approached a police officer to see if there might be an open path to the monument, he looked at us suspiciously and said he’d never heard of such a stone. We had no choice but to move on.

We then transferred via a short metro ride to the GULAG museum, which I’ve previously written about. Thus, this was my second trip there. However, museums with a new guide and a new perspective – such as that given by seeing additional places in the city that help tether its history more solidly to the place you are in – are definitely worth a second trip.

The day was an excellent reminder of the history that lives all around us, ready to teach us if we are willing to look for it.

You Might Also Like

Russian Protest Art that Isn’t Pussy Riot

When most think of Russian protest art today, they think immediately of Pussy Riot, the long-famous, all-female punk movement. These women have, since their “punk prayer” launched them to international notoriety, been heavily covered in the English-language press and heavily studied in English-language academia. However, Russian protest art is a diverse genre with a long […]

The Muzeon and Art Market

Across the street from Gorky Park, on the territory of the New Tretyakov Gallery and the Central House of Artists lies Sculpture Park, which is known as “Muzeon” to locals. It is most famous as a graveyard of Soviet era statues, but also contains much modern art and several themed, sculpted landscapes all in an […]

Moscow’s Seven Sisters – A Short History of Stalin’s Skyscrapers

Moscow’s skyline is largely defined by the seven towering skyscrapers nicknamed “The Seven Sisters.” Also known locally as “Stalinskie Vysotki” (Сталинские высотки – Stalin’s Highrises), they are one of the leading architectural legacies of the Stalinist period. The Soviet Baroque architecture that The Sisters embody is seen by some as unattractive; the buildings themselves are […]

The State Museum of Political History of Russia

Centrally located in St. Petersburg, the State Museum of Political History of Russia examines Russia’s tumultuous political history. It does so in a way that is both modern and quite balanced. Exhibits in the main building are shown in an attractive, recently-renovated tsarist-era mansion with modern technology and artful multimedia presentations. Exhibits give a wide […]

GULAG History Museum

Excursion included in SRAS cultural program for Moscow for Fall, 2017. The GULAG Museum, established in 2001 by writer, historian, and former gulag prisoner A.V. Antonov-Ovseenko, is the only state museum devoted to Stalin’s repressions and the GULAG system. We took a guided tour of this small but informative museum as part of our SRAS […]