The twentieth century was a dynamic period for Soviet composers who often had to work around censorship to create their great contributions to world music.

Under the USSR, artists were expected to produce works that glorified the Communist Revolution and the new lives of the new Soviet masses, often while criticizing the capitalistic West. Soviet composers were called on to produce music that could be understood by the masses and uplift the Soviet people.

Censorship was strenuous, but the Soviet Union did produce composers of note. These artists helped introduce the music of high culture to the Soviet masses and sometimes became internationally recognized. Three examples of Soviet composers and musicians who made a lasting impact in the world of music included Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich, and Mstislav “Slava” Rostropovich.

Meet these amazing Soviet composers below that succeeded in creating art of lasting consequence under extraordinary circumstances.

Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Prokofiev was born on April 23, 1891 on a rural estate in Eastern Ukraine. His father was an agronomist and his mother was a pianist. His mother’s piano playing inspired Prokofiev, especially when she played the works of Beethoven and Chopin.

Prokofiev showed musical talent at an early age, completing his first piano composition at the age of five and his first opera at the age of nine. In 1904, he moved to St. Petersburg and entered the Conservatory. He studied harmony and counterpoint, conducting, and even orchestration with legendary Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov.

In 1908, he made appearances at the St. Petersburg Evenings of Contemporary Music. This musical society was dedicated to the performances of new and controversial works by Debussy, Faure, Schoenberg, Scriabin, Stravinsky, and other modern composers.

His Suggestion Diabolique, Op.4, No.4 was performed to great success.

After this, he was asked to give the Russian premiere of Schoenberg’s Drei Klavierstrücke, Op. 11 in 1911.

The following year, he played his Piano Concerto No. 1 in D flat major, Op. 10 in St. Petersburg and Moscow

In 1914, Prokofiev graduated from the Conservatory with highest honors.

After finishing the Conservatory, Prokofiev took a trip to London where he met Sergei Diaghilev, the famous music patron and founder of the Ballet Russes. Diaghilev commissioned his ballet Ala i Lolli, a story that takes place among the Scythians, an advanced, ancient civilization that once covered a large swath of what would become the Russian Empire.

Diaghilev rejected Prokofiev’s score because of the similarities it had with Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Prokofiev reworked the music into an instrumental suite for concert performance, his Scythian Suite, Op. 20.

After his trip to London, he returned to the Conservatory to avoid the fighting of World War I. He was in Russia during the February Revolution of 1917 and during that summer, composed his Symphony No. 1 in D major, Op. 25. This symphony harkens back to the symphonies of Mozart and Haydn of the late Classical Period, while still using modern composition techniques of the twentieth century.

In the violence and uncertainty that came with revolution, Prokofiev contemplated joining the thousands of Russian intellectuals who had already left the country. In 1918, he left for America, although he did not plan on staying in the West permanently.

While abroad, Prokofiev remained active and ambitious. He composed several works while in the United States and France, however outside of his Piano Concerto No. 3 in C major, Op. 26, his musical works were not received with the acclaim that he hoped for.

Prokofiev also had to compete with the music of Igor Stravinsky, who was having great success in the West. In 1927, Prokofiev went on a concert tour in the Soviet Union that was a huge triumph and made him homesick for his homeland. His Soviet colleagues presented musical life in the Soviet Union with much optimism and convinced him to return home. Prokofiev saw a return home as a way to free himself from the pressures of Western modernism. He was granted a Soviet citizenship in 1932, and made Moscow his permanent home in 1936.

From 1936 on, Prokofiev did everything he could to convince the Soviet authorities of his loyalty. However, until his death in 1953, his music would be denounced as being “bourgeois elite” and straying from Soviet ideology. Along with continuing to compose music in the genres of ballet, opera, and symphony, with his return back home, he began composing for films, which was then common in the USSR for composers.

The first film he composed for was for Lieutenant Kije (1933).

He then turned the music into an instrumental suite in 1934.

In 1938, Prokofiev first started to work with film director Sergei Eisenstein. Their first project together would be the film Alexander Nevsky.

Prokofiev then used the music for a cantata, also called “Alexander Nevsky” in 1939.

Prokofiev collaborated with Eisenstein again in the film Ivan the Terrible, which was originally planned as a three-part trilogy about the life of the Russian ruler, but only two parts were made. Part I was completed in 1944.

Part II was made in 1946, however it was not released until 1958 because of Stalin’s disapproval of the portrayal of Tsar Ivan IV and the oprichniki.

Although Prokofiev’s work was always somewhat controversial in the USSR, it was not until 1948 that this had a major impact on this career. In that year, the Politburo denounced him and his music (the same denunciation affected Shostakovich as well) and banned so many of his works that most musicians would not perform him at all for fear that they might be persecuted as well.

Sergei Prokofiev’s career never recovered and he was soon in poor health and financial straits. However, in 1952, his final (7th) symphony was publicly performed in the USSR.

He died the next year and, although he was not fully “rehabilited” was buried in Moscow’s prestigious Novodevichy Cemetery, a sign that the authorities did recognize his lasting contribution to world culture.

Today, Prokofiev is one of the most produced 20th century composers and his still praised for his unique use of original diatonic melodies. While remaining popular in the former USSR, his works dominate 20th century repertoires in the US – despite the fact that most of his works were written in the USSR.

Tell me more about this Soviet Composer!

|

|

Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Shostakovich was born on September 25, 1906 in St. Petersburg. His father studied math and physics at St. Petersburg University and eventually became an engineer. His mother was a pianist who began giving Shostakovich piano lessons as the age of nine. In 1919, he entered the Petrograd Conservatory and was guided by its director, Alexander Glazunov.

While at the Conservatory, Shostakovich studied piano, composition, counterpoint and fugue, and music history. Shostakovich composed his Symphony No. 1 in F minor, Op. 10 as his graduation piece, which he worked on from October 1924 to July 1925.

The symphony premiered on May 12, 1926 by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra and was well received that Leopold Stokowski gave its American premiere in Philadelphia on November 2, 1928. Around this time, Shostakovich worked at a local movie theater playing the piano for silent movies to earn extra money after the death of father. Film music for Soviet movies would have a major influence on his composition throughout his entire life.

In 1927, Shostakovich joined his fellow Soviet composers, film directors, musicians, and artists in celebrating the tenth anniversary of the Communist Revolution. His Symphony No. 2 in B major, Op. 14, entitled To October, A Symphonic Dedication, more commonly known today as October was a one movement symphony that included a chorus whose lyrics are based on a poem by Alexander Bezimensky, who glorified Lenin for his actions during the October Revolution.

In the summer of 1927, Shostakovich began work on his first opera The Nose.

The libretto of this opera is based on a short story with the same name by Nikolai Gogol. With this opera, Shostakovich wanted to breathe new life into Soviet opera by bringing innovations from film and theater into his music. Unlike conventional operas that contain arias, recitatives and clear distinctions of scene changes, the music in The Nose flows in a single symphonic stream where the singers speak dialogue to music. Here it is perfomed by the The Metropolitan Opera in New York in 2013:

Shostakovich’s second opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, would impact musical composition under Stalin’s rule. The libretto of this opera is based on the story of the same name by Nikolai Leskov. The opera premiered on January 22, 1934 in Leningrad and two days later in Moscow. The opera was such a great success that by the end of 1935, performances had spread even throughout the West with much acclaim.

On January 26, 1936, Stalin attended a performance of the opera. During the performance, he refused to receive Shostakovich in his box and left before the last act. Stalin had many objections to the opera. For the Soviet ruler, the opera did not contain any music that the masses would be able to recognize, the portrayal of sex on stage and in the music was too graphic, and the exile to Siberia of the main characters hit to close to reality as Stalin’s purges were sending thousands to Siberian gulags for hard labor and/or execution. On January 28, the newspaper Pravda published the article “Chaos Instead of Music,” which criticized Shostakovich’s opera. With this article, Soviet authorities aimed to make it clear that all artists were expected to step in line with the Party ideologies and that no one was protected from punishment. After Stalin’s death in 1953, Shostakovich revised his opera and turned it into a film in 1966 with a new title, Katerina Izmailova.

Shostakovich attempted to placate the Soviet authorities with several works that he thought would match what they expected but also would be works of art in themselves. He succeeded with Symphony No 5 in D minor, Op. 47, which was performed with success and is still produced, including by orchestras in the West, today. Here is that symphony as performed by the BBC orchestra in 2013:

Shostakovich would go on to composer ten more symphonies during his musical career, including his emotional Symphony No. 7 in C major, Op. 60 entitled Leningrad, completed shortly after the Nazi siege, which would last 872 days and eventually claim the lives a million residents of that city.

Shostakovich was in Leningrad when the Nazis attacked, but escaped and completed his symphony, which became a rousing symbol of resistance in both the West and the USSR against the Nazis.

As a separate project, Shostakovich planned on composing twenty-four string quartets, one in each key, but he only composed fifteen in total. Most of his quartets were written for the Beethoven Quartet ensemble, which premiered thirteen of the quartets. His String Quartet No. 3 in F major, Op. 73 shows how Shostakovich was able to bring much power and diversity with only four instrumental voices.

In 1948, Shostakovich was formally denounced by the Politburo and most of his works were banned. From this point on, Shostakovich’s life and works were to become some of the most debated among musicologists. He worked diligently to re-ingratiate himself to the authorities such as with his simple and majestic “Song of the Forests,” which praises Stalin as “the Great Gardener.”

However, he also continued to write music that he knew would not be accepted by the authorities and even consciously moved against current political winds. He took chances such as standing up for Joseph Brodsky when that poet was accused by the authorities. Shostakovich wrote Babi Yar, a mournful symphony based on a Russian poem that discussed the fate of the Jews under Nazism, while that poem was still considered highly controversial and when the anti-Semitic tendencies of the Soviet government were already well-known.

He was eventually rehabilitated, joined the Communist Party, and even later attained leadership positions in the arts institutions of the USSR. Many of his pieces that he had written and hidden under Stalin were produced under Khrushchev.

Whatever his politics, Shostakovich is well remembered for composing captivating original works. Today, he was one of the world’s best-known 20th century composers.

Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in F major, Op. 102 was deemed a “perfect match” for the “Steadfast Tin Soldier” in the Walt Disney film, Fantasia 2000.

Shostakovich is also perhaps best known for the frentic complexity of many of his pieces, such as his Piano Concerto No. 1 in C minor, Op. 35. You can watch him on YouTube performing the piece himself with an orchestra:

For those interested in learning more about this enigmatic and controversial, but ultimately successful character, we recommend this documentary, entitled Shostakovich Against Stalin: The War Symphonies.

Tell me more about Dmitri Shostakovich!

|

|

|

Mstislav “Slava”

Rostropovich

Mstislav was born on March 27, 1927 in Baku, Azerbaijan. His father was a cellist who was a student of the famous cellist Pablo Casals and his mother was a pianist. Rostropovich began piano lessons with his mother at the age of four and began cello lessons with his father at the age of ten. At the age of thirteen, he performed his first concerto, which was Camille Saint-Saёns’ Cello Concerto in A minor, Op. 33.

In 1943, Rostropovich moved to Moscow and entered the Moscow Conservatory. He studied the cello, piano, conducting, and composition. He also studied orchestration with Dmitri Shostakovich for three years. One of his earliest compositions, Humoresque, Op. 5 for cello and piano, he composed and memorized in one day and performed it the following day for one of his professors.

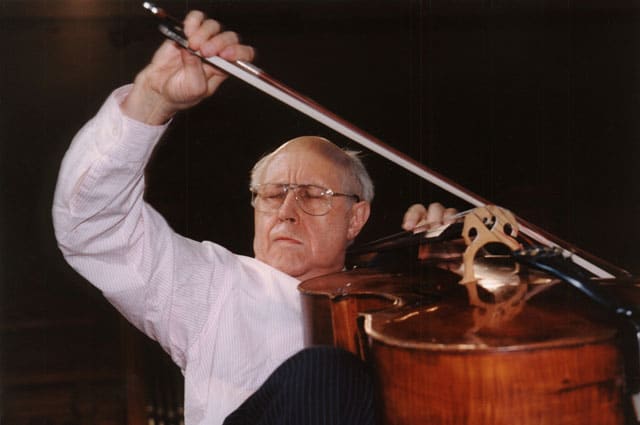

Rostropovich also composed several piano pieces and a quartet. However, he soon gave up composition to focus on his work as a musician. In 1945, Rostropovich won the gold medal in the Soviet Union’s first ever competition for young musicians. His fame as a cellist would only grow and soon many major composers were writing pieces specifically for him to perform. He would eventually premiere over 200 concertos and other cello works.

Rostropovich formed a close friendship with the Soviet composers Sergei Prokofiev and Dmitri Shostakovich. In 1949, Prokofiev wrote his Cello Sonata in C major, Op. 119 for the cellist who gave its premiere on March 1, 1850.

Prokofiev also composed his Symphony-Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, Op.125 for Rostropovich who gave its premiere on February 18, 1952.

In 1959, Shostakovich dedicated his Cello Concerto No. 1 in E flat major, Op. 107 to the cellist who memorized the piece in four days. Rostropovich gave its premiere with the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra on October 4, 1959.

Rostropovich was a strong personality that sometimes clashed with authority – but he did keep playing officially for some time. Here he is playing with the Moscow State Symphony Orchestra in a piece televised in the USSR.

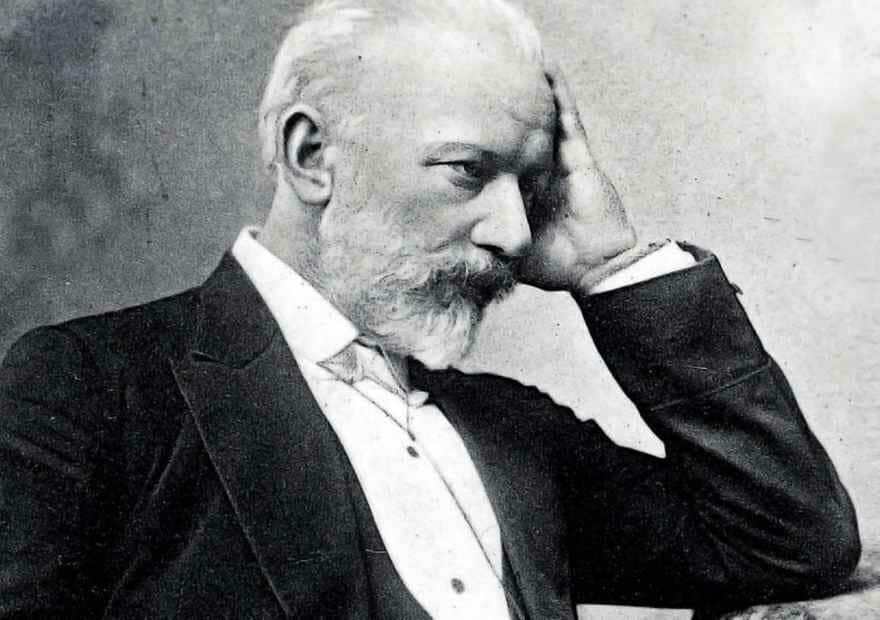

Rostropovich would gain fame as a conductor as well. He made his debut as a conductor in 1969 with Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s opera Eugene Onegin at the Bolshoi Theater. During his musical career, he would conduct many of the world best symphony orchestras.

Rostropovich had a very strong personality; he used his music to bring people from all cultures together and he stood up openly to injustice as he saw it. When his teacher, Shostakovitch was denounced by the Politburo in 1948 and fired from the conservatory the then-21-year-old Rostropovich quit the conservatory in protest. When the Soviet Union crushed the Prague Uprising in 1968, Rostropovich was giving a concert in London and was going to perform Czech composer Antonin Dvorak’s Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104.

https://youtu.be/Tdmk1QstS7E

Many protested at the thought of a Russian playing a Czech composition on that day. However, his performance was a great success and, at the end, he held up the sheet music to give his respects to the Czech composer. As a further sign of support to the Czech people, he played an encore dedicated to those who were mourning.

Rostropovich supported Solzhenitsyn after the writer was denounced for his book The Gulag Archipelago, taking him into his home. With the accumulation of such acts of protest, the Soviet authorities cancelled his tours abroad and performances at home. In May 1974, he left the USSR and his citizenship was revoked in 1977.

In 1977, however, Rostropovich began his tenure as the director of the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington DC. This was the first American orchestra he ever played with as a soloist and under his direction, the orchestra was claimed as the best Russian orchestra outside of the Soviet Union. A documentary about him, with footage of orchestral performances, can be seen on YouTube here:

Not only was Rostropovich a great cellist and conductor, but also he was a strong pianist. He would accompany his wife, the Russian soprano Galina Vishnevskaya (who left the USSR with her husband), in her vocal concerts.

He returned to the Soviet Union in 1990 under Glasnost, giving a concert tour with the National Symphony Orchestra from America. He was received with much acclaim by the Soviet people.

Rostropovich would also give a free concert at the remains of the Berlin wall when it came down in 1989. You can hear him confidently speaking German in this clip as well:

Rostropovich today is remembered primarily for two things. First, his unparalleled mastery of the cello:

But also, of course, his strong personality and his work to push for art without borders and for human rights:

For those who are interested, here is Rostropovich playing the complete Bach Suites for cello, a standard in the cello repertoire.

Tell me more about this Soviet Composer!

|

|

|

Conclusion: The Contributions of Soviet Composers

Prokofiev, Shostakovich, and Rostropovich demonstrated very different ways that artists react to censorship and pressure. Rostropovich managed to be a near-continual fighter until his final emigration, playing his cello and conducting to international acclaim. Prokofiev largely accepted his fate, but also kept creating great music. Shostakovich successfully played the political field to reinstate himself as an official and even leading artist with the regime – yet also continued to occasionally protest and produce work of international note.

This is the power that music and musicians can have for those living under a repressive regime. Despite censorship and hardships, Soviet composers and musicians continued to create and perform because that is what composers and musicians do. That is who they are. One cannot deny who one is, even if one faces extreme consequences for not doing so. Thus, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, and Rostropovich expanded the repertoire of classical music throughout the twentieth century, showing that art can survive censorship, expressing frustration and sadness they felt towards their government, the optimism of defeating the Germans in World War II, and the love they had for their fellow Russian citizens and homeland. They were voices for the people and today, these Soviet composers are loved not only in Russia, but throughout the world.

You Might Also Like

Three Great Soviet Composers of the USSR

The twentieth century was a dynamic period for Soviet composers who often had to work around censorship to create their great contributions to world music. Under the USSR, artists were expected to produce works that glorified the Communist Revolution and the new lives of the new Soviet masses, often while criticizing the capitalistic West. Soviet […]

Book Review of Music and Soviet Power by Marina Frolova-Walker and Jonathan Walker

Marina Frolova-Walker and Jonathan Walker’s Music and Soviet Power, 1917-1932, “trace[s] the transformation of pre-Revolutionary Russian music culture into Soviet music culture over the space of fifteen years”[1] focusing on how the music changed and adapted to the communist ideology of the new Soviet Union. It takes us through the tumultuous experimental period from the […]

Tchaikovsky: The Life and Modern Legacy of Russia’s Great Composer

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky is one of the most popular composers of all time and produced numerous symphonies, operas, piano concertos, and ballets. The Russian composer’s works can be found today not only in concert halls across the world, but also used in popular culture as recognizable and emotionally affecting pieces. He also remains a constant […]

Chopin Museum, Warsaw

In Warsaw, large, elegant, and beautiful willow trees grace many of the parks within the city. These are the same willow trees that inspired many of the outstanding musical pieces of prodigy composer and native Pole, Frédéric Chopin. Signs of Chopin’s legacy, like the willows that inspired him, can also be seen across the city. […]

Four Examples of Russian Music in American Popular Culture

Throughout the Cold War to the present day, there has been tension between the United States and Russia in the political arena. However, Americans have used Russian music in creating elements of American popular culture. Appropriated Russian songs include classical pieces like “The Flight of the Bumblebee,” which is often used to represent speed and […]

Rimsky-Korsakov Memorial Apartment Museum

Saint Petersburg has been called home for several renowned artists and musicians, including figures in classical music. Admirers of Russian opera and orchestra should pay a visit to the apartment museum of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, a prolific composer and member of the “Russian Five.” This nationalistic group of 19th century composers, which included Mily Balakirev, Modest […]