The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts in Bishkek showcases native art forms as well as painting, sculpture, and other works, highlighting those created by Kyrgyz artists. The museum is centrally located and is perfect for a day trip with an abundance of restaurants and cafes nearby. The article below will tell the history of the museum and why SRAS students on programs in Bishkek have loved attending it – and what they’ve found to criticize about it.

Up to date information on tickets, audio guides and personally guided tours (in Russian, Kyrgyz, or English), can be found on their website.

History of the The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts

The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts in Bishkek is named after Gapar Aitiyev, one of the first Soviet-Kyrgyz artists. Aitiyev was born in modern-day Osh, Kyrgyzstan’s second largest city, in 1912 and went on to study at the Moscow Technical School in Fine Arts. His paintings spanned most of Soviet history and featured poetic landscapes of Soviet-Kyrgyzstan through a mixture of Soviet Realism and Neorealism artistic styles. Some of his most famous works include Athletes (1938), The Kolkhoz Yard (1946), Midday on the Issyk-Kul (1954), and The Outskirts of Andizhan (1967). In addition to his art, Aitiyev was a Soviet hero who fought in War World II. In 1967, he was awarded the Toktogul State Prize of the Kyrgyz SSR and the Order of Lenin. His former studio is today a museum itself dedicated specifically to him.

When the museum first opened in January 1935, it was funded and supported by the Communist Party in an effort to promote traditional forms of Kyrgyz art. Notable Kyrgyz artists were closely involved in the founding of the museum. The original collection of 72 pieces was curated by Semyon Chuikov, the founder of Kyrgyz painting. Also involved in the museum’s founding was Gapar Aitiev himself, another one of Kyrgyzstan’s first professional artists.

Donations soon flooded in from across the Soviet Union and Bishkek’s small photo gallery quickly became a blossoming hub of fine arts. Its ethnographic collection was first established in 1967. There are currently about 3,000 ethnographic collections at the Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts. While there are still a number of paintings by famous Russian artists, Kyrgyz fine and applied art dominates the museum’s collection. The museum boasts a fine collection of Kyrgyz applied art, such as felt products, wood carvings, embroidery, leather goods, and Kyrgyz jewelry.

To date, the museum collection has close to 18 thousand items in storage. Today, the museum is owned and operated by the Kyrgyz Ministry of Culture, Information, Sports, and Youth Policy who oversee the day-to-day operations and long-term maintenance of the premises and collections.

The building that currently houses the museum was opened in 1974. Designed by Shailo Djekshenbaev, an architect born in the Kyrgyz village of Sailyk, the structure is a perfect example of the Soviet brutalism that was popular in 1970s Kyrgyzstan. In keeping with the theory of Gesamtkunstwerk (or, “total art”), that was central to that style, Djekshenbaev crafted the building in such a way as to itself be an exhibit. From the protruding concrete overhang to the art deco-like flooring, the design embraces both utility and aesthetics to create an immersive art experience which, fifty years later, has become something of a Mecca for admirers of brutalism. As such, the museum’s premises serve to reinforce the gallery’s mission to find threads of fine art through all walks of Kyrgyz life and culture.

Museum Structure

By H. Lee Sullivan

The museum’s four main exhibits (applied arts, paintings, graphics, and sculptures) can be divided into three main periods. The first covers nomadic Kyrgyz history and consists entirely of applied arts. As a people always on the move, Kyrgyz art was originally found in the most practical tools of everyday life. The museum’s collection of carpets, jewelry, and cookware highlights this and allows visitors to find such beauty through their own perspective.

The second period covers the Soviet-era and consists of paintings, graphics, and sculptures. The establishment of cities, industrialization, collectivization, and political atmosphere transformed the Soviet Kyrgyz SSR from a nomadic to sedentary lifestyle. This transformation is captured visually by the museum’s shift from applied arts to framed paintings, graphics, and sculptures.

The final period covers post-Soviet Kyrgyz art and also consists of paintings, graphics, and sculptures. The nomadic roots, Soviet history, and contemporary identity of Kyrgyzstan are all reflected in the museum’s modern art. Additionally, the museum hosts a miniature bazar on its main floor where visitors can purchase pieces made by local artists.

For more on the development of art in Central Asia, see this article on our site.

Guided tours with interesting and well-spoken guides can be booked in advance and are offered in Russian, Kyrgyz, or English. The guide who escorted my group through the museum spoke excellent English and her explanation of each exhibit was interesting and easy to understand.

Audio guides are available for select exhibits, namely the applied arts and paintings exhibits. Pieces with audio descriptions are labeled with a small image of headphones and a number. To hear the audio, punch the number into the audio guide and hit enter. All audios are translated in Russian, Kyrgyz, and English. The English audio guides are spoken by a native English speaker and are easy to understand. However, the quality of each audio varies. Some pieces have in-depth descriptions with background information on the artist or analytical perspectives, while others have a simple and more literal description of the piece’s visual appearance. Visitors are required to trade their passport for an audio guide at the check-in desk.

The Kyrgyz Museum of Fine Arts takes visitors on a journey through the storied histories of Kyrgyzstan, all the while showcasing the beauty of utility in the nomadic lifestyle. Furthermore, it captures the progression of Soviet history through Kyrgyz art and leaves visitors with a sense of how the modern Kyrgyz identity came to be. Those interested in Central Asian studies, applied arts, Soviet history or related topics would benefit greatly from a trip to this museum.

A Deep Dive into the Exhibits (Spring, 2020)

By Mikaela Peters

As part of the Central Asian Studies Program, SRAS students took an excursion to The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts in Bishkek. While this wasn’t my first time to the museum, this was my first time with an English-speaking guide who helped us to understand the art that we were looking at. Likewise, the first time I had been to the museum, approximately two years ago, it was under renovation. This time all of the exhibits were available for viewing.

The first floor contains the museum’s rotating, temporary exhibits, while the second floor contains their permanent artworks. There are over 3,000 art pieces contained within this museum from forty different regions. Out of these, 2,000 pieces were granted to the museum for exhibition from the State Gallery and the Museum of Oriental Arts. The pieces contained in the museum range widely from artifacts used by the nomadic people of Kyrgyzstan, including quilt work and external garments, to paintings and sculptures from France, Greece, Egypt, and a few others.

We began our tour by considering wooden and leather items used by the nomads. This section also included silver jewelry worn by women during this period, which was the preferred type of metal. Aside from bracelets and necklaces, silver was used for ornamented female headdresses. Stones were considered to be the most important part of Kyrgyz jewelry. Some of these jewelry pieces that were displayed were not for everyday life, but for special occasions only.

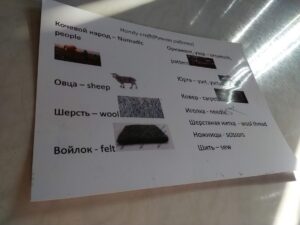

We also learned about Kyrgyz felt art, which is still used to make traditional rugs and other items. Usually two colors were involved as two layers of felt were placed one on top of another and a pattern was cut into the top layer to reveal the bottom. There were various styles for these types of rugs, including those called mirror, butterfly, modern, whole, embroidery, and plate.

Our discussion of Kyrgyz felt was continued at an arts and crafts class that we had afterwards at our school. Our task was to sew together two pieces of felt to create a phone case for ourselves. During this class, we also learned new Russian vocabulary words that were related to this task: nomadic people, sheep, wool, felt, pattern, yurt, carpet, needle, wool thread, scissors, and to sew. It was very interesting to note that she assumingly approached all of the men in the class, presuming that none of them knew how to sew. This was only partially true. But she was much keener on helping them since she seemed to think they needed it. This was yet another manifestation of the gender norms surrounding domestication and house work that are still seen in Kyrgyzstan, even in this modern era. This class was a great compliment to what we learned at the museum.

At the museum, we also saw some other nomadic items such as traditional cookware for food, camel leather flasks and cups, a wooden trunk for food storage, and a contraption called a kur-kur, which was used for the transportation of kumis, a Kyrgyz national drink made from fermented mare’s milk.

We then looked at some hanging yurt dividers, which looked a little similar to the rugs that we had just seen. The purpose of such was to divide the kitchen of the yurt (a traditional, collapsible tent-home) from other parts of the yurt. We then learned that two main colors primarily are used in Kyrgyz folk art: red and blue. Red is used as the national color, symbolizing bravery. Blue is used to represent the celestial bodies.

We then saw handmade clothes, such as men’s pants and a female skirt. The men’s pants had a fish on them, which meant that they were from the Issyk Kul region. As for the skirt, we were told that it had belonged to a married woman. After the birth of her first child, a skirt is given to the new wife from her mother-in-law. The skirt is made of warm material as its purpose is for moving between fields. The next item we saw was a beaded headdress of a married woman from the south of the country. In these styles, circles symbolize the sun. Kyrgyz folk art favors rich embroidery and often decorations of roses and tulips are used. For men, a traditional hat, known as a kapok, which was made from pumpkin, was displayed.

While these hats are typically made from sheep’s wool, this had in particular has won prizes at the world exhibition for its uniqueness. Finally, in this section, we saw two saddles, one for use by each gender, which were inlaid with precious stones and covered with leather.

The next portion of the museum included contemporary art, from the 1960s onward. The first items on display in this section started out with a similar look to the large felt carpets we had just seen. But instead of patterns, they had people and animals on them, which had traditionally not been used in Kyrgyz art previously, due to superstition. But with many new up-and-coming Kyrgyz artists having gone abroad to the Moscow and Leningrad Universities to study, they were beginning to combine the old ways of art with new ones.

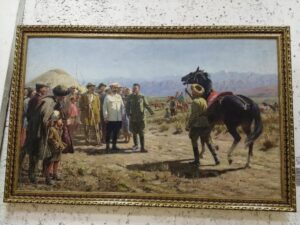

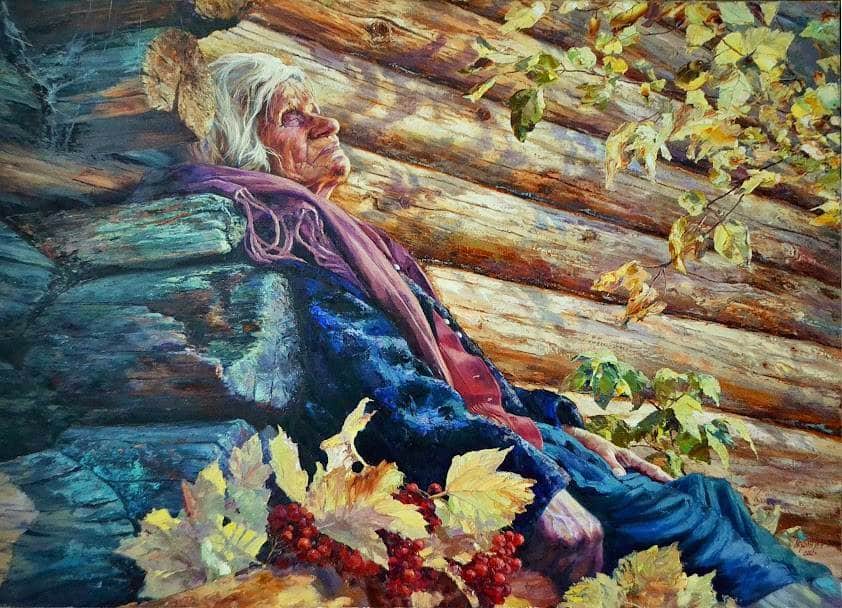

Afterwards, we moved into the paintings section of the museum, these paintings were as old as the 1930s and up. Beginning in 1934, S.A. Chukov, began painting a series of portraits and even won the Stalin Prize. His most famous picture is the Daughter of Soviet Kirghizia. For this reason, Chukov was known as the father of Soviet art.

The majority of the paintings in this section were from the 1960s. Our guide informed us that many were categorized as social realism. Many artists who painted in this form were from the Leningrad School and, therefore, kept to the traditions of Russian art. An example of one of these was an oil painting of a shepherd grazing with a dog, called Cowboy, painted by Viktor Tyurin. Its image was published in many popular newspapers when it debuted.

In this same section, our attention was then directed to the work of Kulchoro Kerimbekov, a landscape master, who often painted scenes of fishing and shepherding. He painted in bright color combinations. The example we were shown, Fisherman, was set in Issyk-Kul, depicting an atmosphere of labor.

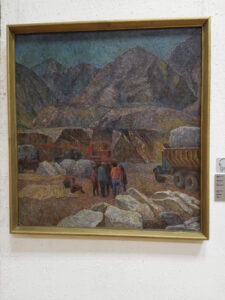

Another artist, V. A. Kim, who did not have cultural ties to the region, came to Kyrgyzstan specifically to paint the Kyrgyz landscape. His choice of colors differentiated his work. He himself, unlike the other artists in the museum, graduated from a school in Central Asia, more specifically, the Tashkent Art Institute, rather than from Russia. His main landscape interests include mountains and industrial themes. The paintings we saw were named Marble and On a Visit.

There was yet another noteworthy painting depicting social strife between rich woman and poor man who had fallen in love. This painting by J. Kadraliev was entitled Farewell. Later on, a song was written and dedicated to the woman in the picture. Like the artists mentioned above, this painter, too, was focused on the landscape in the background. The figures in the foreground were monumental compared to the landscape encompassing them, thus showing the primary role they played in nature.

Between the painting and sculptures sections, we first saw local art works of both genres. One sculpture was of Manas along with his wife and advisor, Kanykei. There was also art dedicated to Chingiz Aimatov, one of Kyrgyzstan’s greatest writers. A sculpture called Mother Dear that commemorated the poem written by Chingiz Aitmatov, which in part describes the horns of a dear. There was a painting known as Red Apple, or First Teacher. There was also a bust of Chinghiz Aitmatov himself, in addition to the other sculptures dedicated to his poems.

Aside from all of the permanent exhibits, I was able to take a look at the artwork created by the local artists, which was displayed on the first floor, and which rotates every so often. I, myself, was glad to have had this experience with the help of an English-speaking guide so that I was best able to understand the different art pieces that I was looking at it. Since many of these pieces were not available for viewing the last time I was at the museum, I was happy to be able to experience the museum in its entirety this time around. Not only did this museum help me learn about Kyrgyz art, but also a little more about Kyrgyzstan’s history.

A Visit to The National Museum of Fine Arts in Bishkek (Fall, 2018)

By Daphne Letherer

There are three major museums in Bishkek: The State History Museum, Frunze Museum, and The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts in Bishkek. Chances are you will be taken to The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts in Bishkek on an as part of your SRAS Cultural Program in Bishkek, so you will enter for free. If you want to go independently, however, the entrance fee for students is low (20 som, or about $0.28). The museum isn’t far from Ala-Too Square and can be reached easily by bus or marshrutka. It was established in 1935, and the architecture clearly reflects Soviet influences. The museum has two floors, with the second housing the artwork and artifacts. The first floor houses temporary modern art exhibits (though I’m not sure how often they change). If you go on the excursion with the school, you will have a tour guide who speaks English. They will guide you through the rooms, providing interesting explanations about the art, such as when and how and by whom the pieces were made. It is the largest collection of art in Kyrgyzstan, but you don’t need an entire day to visit the museum. You won’t need more than a couple of hours even if you take your time looking at everything.

When you first arrive at the top of the stairs, there will be artifacts, including felt rugs and clothing. There is jewelry and horse-riding gear as well, giving you a taste of traditional Kyrgyz culture. Rugs hang from the walls, showcasing different kinds of designs and allowing you to see a piece of home from a traditional yurt. As you continue, there are paintings and sculptures. There are textiles, including non-traditional felt wall hangings as well as pictures made entirely of felt, which is itself a staple of traditional Kyrgyz life and handicrafts. There is a section dedicated to an artist who depicted Kyrgyz life through traditional portraits. This was one of my favorite sections because the subjects of the paintings were so realistic, I almost felt like I was there in a field watching the subjects ride horses, or across the table listening to major Kyrgyz figures talk. Past this section you will find portraits of soldiers and Soviet officers, as well as a few solemn war scenes. The final display showcases contemporary art, some of it political, some of it abstract.

When I visited, a young woman was our guide, and it was her first day on the job. She was very nervous to speak in English about the artwork, but she did an excellent job. She occasionally spoke in Russian when she didn’t know how to discuss the topic at hand. One of the school administrators, Asel, went with us, and she translated what we didn’t understand. Asel also couldn’t stop herself from touching the rugs and felt artwork, despite uncomfortable warnings from our tour guide. Overall, I enjoyed my visit to the art museum. I’m glad I had the chance to see Kyrgyz art, traditional and contemporary. Kyrgyz culture goes beyond yurts and horses, and the Fine Arts Museum is a great way to experience what else art in Kyrgyzstan has to offer.

A Few Critical Points of The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts (Summer, 2022)

By Sophia Monte

In addition to fine art and ethnographic art, the museum also has a number of reproductions of famous artwork from a range of artistic traditions and disciplines. One gallery room exhibits reproductions of famous paintings by European artists such as Van Gogh, Renoir, Degas, Monet, Picasso and Chagall. In another area of the museum there are a number of sculpture reproductions from varying artistic traditions, such as ancient Egyptian and classical Greek and Roman art. These reproductions make for a confusing experience for visitors, since the pieces that are reproductions are not clearly distinguished from original art. The museum lacks panels most art museums would have to provide the viewer with information about particular art movements or other thematic organizing elements that help distinguish exhibits from each other. Thus, the visitor is left without important historical context that would illuminate the thematic organization of the exhibitions. For an English speaker, it is difficult to navigate the museum as there are no English translations on plaques and the English audio guides only cover select exhibits.

Fortunately, the Museum’s website provides an extensive list of museum paintings and sculptures with exceptional explanations of each piece and the artist in Russian and Kyrgyz. There are hundreds of pictures of paintings and a few pictures of sculptures and other types of art with information about the medium used, dimensions of the piece, historical art period under which each particular work falls and the artist’s bio. Some even include detailed artistic analyses and art historical background. Unfortunately, none of the museum’s applied art appears online, although there is a section heading on the museum website dedicated to this part of the museum’s collection.

The museum’s building is old and does not seem to have the facilities to keep its art in good condition. Many of the frames that display the artwork are in poor condition and bear visible dents and scratches. There is a gallery space in the museum, off-limits to visitors but still visible from a distance, that holds a lot of art stored away in a haphazard manner. Although there is no artwork as valuable to artistic history such as the Mona Lisa in the Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts, there is something sorrowful about the seeming lack of proper care for the artwork that permeates the museum environment.

Reasons to Come Back to The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts (Summer, 2022)

By Olivia Route

The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts in Bishkek on Sovietskaya, just across from the opera house, is a two-story building full of traditional Kyrgyz arts, contemporary art styles, and traveling exhibits. Today was the second time I visited the museum for a number of solid reasons. I was nearby, it’s inexpensive, and I really enjoyed it the first time.

As you walk into the museum, even before you’ve realized that the касса (ticket desk) is located to off to the left and behind you, you’re assaulted by color. The main lobby is full of tables of local artists and craftspeople, who have тапочки (slippers), scarves, bags, wall-hangings, miniature yurts, and a number of other kinds of souvenirs out on display. After you get your ticket you can poke through their beautiful wares and try to justify a craft purchase because your student ID means admission cost less than dollar.

After looking at all the pretty souvenirs, you can move to the right into the first exhibit, a room full of Kyrgyz crafts isolated from the rest of the collection. Most are presented without comment or even those little date plates. They leave you guessing. That pretty round cloth with the ropes? Another woman visiting the museum tells her friend it’s an old-fashioned saddle. There’s a pair of pants, a skirt, and lengths of embroidered and embellished fabric. It’s not a huge room, and when you’ve finished there, you exit the way you entered, back into the vendors’ lobby.

To get to the main museum from the lobby, head up the stairs opposite the front door. They’ve got a huge flower mosaic behind them – snap a shot and then put your camera away for the rest of the tour, or the babushka-security guards will be very unhappy with you.

The second floor of the museum has the main collection of art and artifacts. In this open space at the top of the stairs, there are a number of standing display cases that showcase Kyrgyz art and jewelry from a variety of time periods.

The walls are covered in patterned Kyrgyz felt rugs, called ala-kiyiz or shyrdak (the name depends on which labor-intensive process created them). They can be incredibly ornate or fairly simple, and though they range in color, most are red and blue or combinations of red, blue, green, and brown. This form of Kyrgyz art was recently added to UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding as they “provide Kyrgyz people… with a sense of identity and continuity linked to their nomadic lifestyle.”

Off to your left is the medium-sized traveling exhibition hall. The current exhibit in this room is a collection of Japanese Dolls and prints – and in this room, photography is permitted and encouraged. To the right and behind the stairs is room with another collection of Kyrgyz wall hangings. Most are contemporary pieces done in homage to traditional styles. This room also connects to another hall full of beautiful landscape paintings, but that hall is currently closed.

In the hall at the top of the stairs off to the right is the entrance to a very large hall of 20th century Kyrgyz paintings and a few sculptures. This hall is probably one of my favorite parts of the museum. It’s got a number of beautiful paintings depicting a world away from Bishkek (picture a few people standing next to a tan yurt, dwarfed by what is probably the Tian Shan mountain range). There are benches in front of those paintings so you can take a seat and lose yourself for a bit. This room also includes a number of paintings with titles that generally made me want to go home and research the region’s history. There’s one from 1933 that shows a crowd of people being herded by men on horseback through village streets. A man in foreground restrains his friend who is visibly angry. The title is «После Восстания» or “After the Uprising.” There’s a scene from 1930 entitled «Возвращение из красной армии» (“Return from the Red Army”) with a young man in uniform, standing in a village amongst a group of happy faces. One of my favorites in this room is a beautifully simple 1933 portrait of a red-cheeked Central Asian girl. Her head is wrapped in a dull yellow scarf that winds down around her shoulders and she watches something out of the corner of her eyes, maybe a little suspiciously. Amongst a collection of works with very descriptive and sometimes lengthy titles, hers fits her simplicity – «Комсомолка» (“Komsomol Girl.”) There are a number of other portraits from the 20th century, many with familiar names because they now have their own streets in central Bishkek. It’s a great combination of scenic, historic, and still-life paintings, making it definitely the longest stop in the overall museum excursion.

Before leaving the museum, if you have time, check out the auditorium off of the center of the main ground floor lobby. During my first visit I passed it over, but on my second, I was drawn in by the echoes of shouting and applause. The approximately 150-person venue was having a gigantic, multi-round arm wrestling tournament. While an unexpected stop on my museum tour, the contest was a funny ending to a thoroughly enjoyable afternoon.

You Might Also Like

Museums as Self-Care

In 2018, doctors in Montreal began prescribing visits to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) for patients experiencing depression, anxiety, and other health issues. This innovative approach to mental health treatment was launched under the initiative of the MMFA in collaboration with Médecins francophones du Canada (MFdC). The program allows physicians to provide patients […]

Guide to Bishkek’s Top Museums for Students

The Kyrgyz were largely a nomadic civilization up until the 20th century. The city of Bishkek has a number of museums documenting this fascinating history as well as the development of the arts and sciences in Kyrgyzstan. These museums were mostly established during (and today are often unchanged from) Soviet times, including a number of […]

The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts in Bishkek

The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts in Bishkek showcases native art forms as well as painting, sculpture, and other works, highlighting those created by Kyrgyz artists. The museum is centrally located and is perfect for a day trip with an abundance of restaurants and cafes nearby. The article below will tell the history of […]

The National Historical Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic

The National Historical Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic is a great place to get started when visiting Kyrgyzstan. The museum’s extensive collection of more than 90,000 exhibits includes artifacts from Kyrgyzstan’s prehistory, from its ancient Silk Road era, Soviet-era history, and modern state. Culture exhibits focus on Kyrgyz nomadic culture, traditional handicrafts, and the musical […]

The Evolution of Art and Painting in Central Asia

While Central Asia has a long, rich history, the modern nations of the region are a direct result of 20th century colonization. Prior to Soviet interference, the many ethnic groups and distinct societies of the region were loosely grouped under the geographic term of Turkestan. Under Soviet control, the region was divided into the Turkmen […]