The following are six modern Russian artists who have left their mark on not only modern Russian art, but who are also known beyond Russia’s borders as well. Each has gathered critical acclaim and, as is always the case in the art world, at least some critical derision. Not all are ethnic Russians – but all hold Russian citizenship and have at least lived and worked in Russia for most of their careers. Russia is a multi-ethnic state and thus its art scene must be understood as multi-ethnic as well.

If you want to get to know modern Russian artists, these are six to start with.

Oleg Kulik – Performance Artist, Painter, Sculpter

By Kate Spencer

Oleg Kulik (Олег Борисович Кулик) is a photographer, curator, and sculptor. He was also one of Russia’s first performance artists. Through his work, he presents commentary on politics and power, Russia and the West, as well as humankind’s relationship to nature. Kulik’s artistic work “has continued to provoke and unsettle audiences globally.”

Early Life and Education

Kulik was born in Kiev in 1961. He graduated from the Kiev Art School in 1979 and later went on to graduate from the Kiev Geological Survey College in 1982. After serving two years in the military, Kulik moved to Moscow in 1988 where he began his entrance into the artistic world. In 1996, Kulik was awarded a scholarship for his work by the Berlin State.

Curation as Art

Up until the early 1990’s, Oleg Kulik exclusively worked on plexiglass art pieces.

Early on, he became an exhibitor of the Regina Gallery and continued to work there until 2018. He sought, as curator, to make the display of the art as much an art as the art itself. For example, in “Self-standing Art,” Oleg Golosiy’s paintings were moved on wheels around the gallery hall. In another example, “First-hand Art,” soldiers held the art pieces.

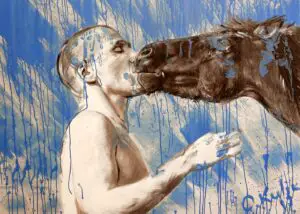

Performance Art and Oleg Kulik’s Animal Breakthrough

One of Oleg Kulik’s first performances was held in 1992 at the Regina gallery. In this performance, a butcher slaughtered a pig in the exhibition hall and then gave the meat out to visitors.

Kulik first achieved fame in 1994 with his performance as a dog, dubbed a “shocking, provocative performance with an animal twist.” Called the “Mad Dog” or “Last Taboo Guarded by Alone Cerberus,” this performance included Kulik himself naked in the frost, chained up like a dog. He barked, pushed onlookers over and bit them. At one point, he rushed into traffic and stopped cars.

He has since had multiple other performances where he assumed the role of a dog, as well as other animals such as a bird, bull and an armadillo.

There are many layers of interpretation to his performances, which have been described as a culmination of intense disgust with the modern world and art. They are meant to foster empathy for those who are not a part of or welcome in the modern world. In one of his dog performances in America, “I bite America and America bites me,” there is a possible metaphor comparing a hungry and abandoned dog to an artist who does not fit into the contemporary art world.

Oleg describes the dog he plays as a “metaphor of the borderline state of the human being positioned between nature and the socium.” He explains his belief that modern day civilization is no less wild than “the former wildness,” and that man can no longer survive out in this wilderness, just like the abandoned dog.

Beyond this, there is a rejection of anthropocentric ideals, meaning he rejects the idea that humans are central to existence. Kulik’s animal-artist performances are connected to his concept of zoophrenia, which, for Kulik, refers to the reversion of man to his “other state.” This is not supposed to be a sort of regression into an animal state, but an embrace of the “non-anthropocentric Other of the human being.”

In another performance, he ran for president of Russia dressed as a bull on the platform of “anti-human” or “Animal Party” politics. He expressed the idea that “the human being is losing its essence, its animal element.” Kulik has voiced that the best social order would be founded on the idea of zoocentricism where man is only a part of the biosphere, living symbiotically with nature.

There is an embrace of nature, not only through increased empathy and value towards animals, but a connection within oneself to nature.

Kulik’s Art as Expressly “Russian”

Kulik has been described as the most “Russian” of Russian artists. Russian’s have innate differences from Western and European norms, because of their unique history and geographic location. “The overwhelming majority of Russian artists conceal this innate marginality as a defect.” In contrast, Kulik has extremely embraced, and even dramatized this “Russian nature,” evoking “delight and horror in Western man.”

Criticism of Kulik’s Work

Kulik has been described as a despot and tormentor in his art, for example, for having soldiers hold paintings for hours in their outstretched arms. He has also been called a masochist, for the pain and suffering he endured during his performances. Kulik can be seen as a hedonist, specifically in his zoophilic work with animals.

His work and performances have depicted him in what can be described as “interspecies sexual encounters,” particularly White Man, Black Dog and Deep in Russia. These works are highly controversial and when asked to elaborate on these activities he said “I am not defending any sexual contacts. And I do not attack any of them. I defend love, intimacy, and mutual understanding.”

Today, Kulik has discontinued his dog-man performances and has moved away from performance art. He created an exhibit on religious art in Russia. Most recently Kulik was a part of the exhibit This is All You, which is a contemporary art exhibition which is a collaboration of many Russian artists.

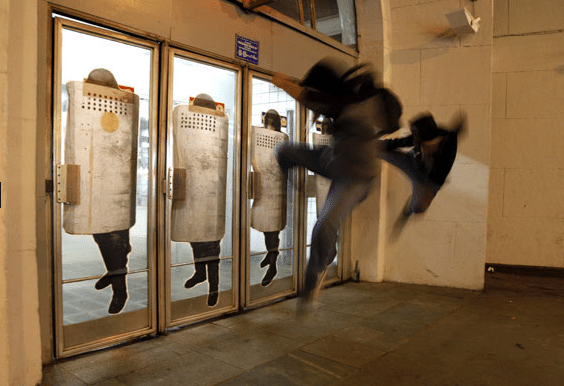

Above: Associated Press news coverage about one of Oleg Kulik’s dog performances in the US

Olga Bulgakova – Painter

By Elizabeth Rodgers

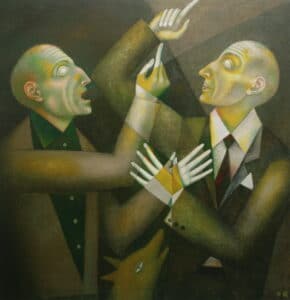

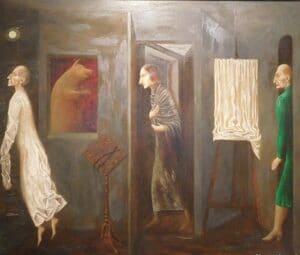

Olga Bulgakova began painting in the seventies, helping to found the surrealist/ symbolist resurgence in Russia. Her work has continued to evolve, staying consistently cutting-edge and thought-provoking. Today she’s still one of the most influential contemporary Russian artists. Early in her career, in 1975 she won the Grand Prize of the International Competition of Young Artists in Sofia, Bulgaria. In 2003 she received a Silver Medal from the Russian Academy of Fine Arts. In 2007 she was made an associate member of the Russian Academy of Fine Arts.

This Russian modern artist displays a master’s attention to fine detail and an innate sense for visual meanings. Perhaps as a side effect of her deep understanding of the codes and hidden messages of the visual world, Bulgakova’s work has continued to take her to new levels of symbology. She began in the seventies and eighties with several cycles depicting the dramatic and literary arts. For these studies, she delved deep into the language of visual codes, endeavoring to represent a literary feeling on canvas. In the nineties her works became more heavily symbolist and intentionally dream-like. For these works, she employed geometric shapes, overlapping images and common dream symbols in order to represent meaning. Since the turn of the millennium she has used geometric shapes and abstraction much more extensively. Her series Angels and Biblical Sketches (2007-11) notably utilizes religious language and symbols.

Early Life and Work

Bulgakova was born to a family of artists in Moscow in 1951. Her parents, Vasily Ivanovich Bulgakov and Matilda Mihailovna Bulgakova, were both painters. When the Soviet Union entered World War II, Vasily fought at the front while Matilda worked as a tutor in Karaidel (Bashkiria) children’s home.

Olga followed in her parents’ footsteps and attended courses at the Surikov Art Institute, from which she graduated in 1975. The following year she became a member of the Moscow Union of Artists as well.

The artistic movements which arose around that time were influenced by artistic movements from abroad, which had begun filtering into Russia. Young artists began to appear who had grown up after Stalin’s death in 1953, having enjoyed relatively greater freedoms of expression, increased knowledge of their avant-garde forebears, and more opportunities for international artistic exchange than had the previous generation. Though the seventies are remembered for being largely artistically stagnant due to the unpredictable political climate concerning art, several rich schools of thought emerged in Russian artistic expression. This includes the symbolist and surrealist movements in which Bulgakova was involved.

In the seventies and eighties she created serieses with a focus on theatrical and literary personalities and in particular the mythos of the “artist.” She began the cycles Theater and Transformation in 1975 and worked on them through 1985. In her Gogol series, from 1978 to 1985, Bulgakova sought to capture on canvas the drama and myth surrounding the author Nicolai Gogol. She also sought to reinterpret his literary language in a visual form with a complex system of visual symbols to mimic his style. For instance, Gogol’s writing evoked great emotional reactions with seemingly banal dialogue. Bulgakova succeeded in evoking that Gogolian feeling of “magical chaos” by creating elusive sparks of interest, as in off-side whispers. She also expressed Gogol’s nightmareish take on the world by utilizing dark and gloomy elements. There is a sense of something supernatural in the resultant works, as if one is having an out-of-body or otherworldly experience.

By breaking down Gogol’s prose into emotional components to be displayed visually, Bulgakova ultimately began to explore the landscape of visual language itself. At times, Bulgakova also sought to capture the creative process itself – a slow unraveling of reality and a glimpse at the abyss.

Bulgakova’s work continued to evolve. Over the eighties and nineties, her artwork had become very concerned with the task of translating from the literary to the visual. In the nineties, she extended that logic into an exploration of the basic components of visual language. Her work began to play more expansively with the language of symbols, either from dreams, history, or daily life. Bulgakova’s true subjects in these pieces are read through a combination of visual messages.

It is interesting to note that because of Bulgakova’s increased usage of symbols, her paintings’ central messages or subjects were correspondingly deconstructed into their component parts. Her works from this period consequently create a powerful emotional tension. The heavy compartmentalization inherent in the pieces means that one’s artistic enlightenment comes at the price of comfort. The world is split open in segments, like puzzle pieces, and the viewer is deprived of his or her knee-jerk attachment to the notion of a cohesive and harmonious universe.

Later Life and Work

At the end of the nineties, Bulgakova’s work underwent another change. Most notable has been the disappearance of figurative reference points within her paintings. The same code which before lent itself to a symbolic and metaphoric artistic language suddenly became more concerned with abstract and geometric imagery. In a recent series, the viewer is no longer given the task of reading an emotional state through a complex language of symbols. A prime example of Bulgakov’s turn towards abstraction is her 2002-2004 series Archaisms, which features overlapping geometric shapes.

Some of her new series, however, such as Nomina (2005-2006), Matriarchy (2007), and Biblical Sketches (2007-2011) feature concrete subjects as seen through an abstract lens. So far, these abstracted subjects tend to have an allegorical or religious value. These works include Return of the Prodigal Son and The Sacrifice of Abraham. She has also done a series of abstracted, life-size angels. As before, Bulgakova continues to play with the language of symbols, now utilizing allegory, geometric shapes and nostalgic reminders.

Throughout her career, Bulgakova has worked closely with and has frequently exhibited alongside fellow artist Alexander Sitnikov. Their works were shown together at The State Tretyakov Gallery and at The Radishevsky Museum, for instance, and she has held exhibitions in Western and Eastern Europe as well as the US to great acclaim.

Zurab Tsereteli – Sculptor

By Taryn Jones

Zurab Konstatinovich Tsereteli was born in the Georgian capital of Tbilisi on January 4, 1934. A somewhat controversial figure, he is a well-known painter, sculptor, architect and decorator. He is by far, however, best known best for his sculptures of monumental size and often controversial abstraction.

Political Connections

Perhaps Russia’s best politically-connected artist, he once served in the Public Chamber of the Russian Federation (an advisory organ to Russia’s legislative organs) and is the long-time President of the Russian Academy of Arts. He has been named both a People’s Artist of the USSR and a People’s Artist of the Russian Federation. He is also the director of the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, the director of the Museum and Exhibition Complex of the Russian Academy of Arts, and has his own art gallery (which features mostly his own works).

Internationally, he is also president of the Moscow International Foundation for Support to UNESCO, the UNESCO international chair of Fine Arts and an official UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador. He is also a member of European Academy of Arts, and participates in France and Spain’s Academies of Art as well as his native Georgia’s (where he still holds citizenship) Academy of Science. He has taught art at the State University of New York and the College of Arts and Science at Brockport, NY.

More recently, Tsereteli has distinguished himself as a philanthropist, and has donated several of his works to charity as well as advocating for the construction of both orphanages and facilities for recreation.

Early Work

Tsereteli was raised in an artistic environment, as his uncle was the famed Georgian artist Georgiy Nizharadze and the family was often visited by Georgian artists such as Sergo Kobuladze, David Kakabadze, Ucha Dzhaparidze, Apollon Kutateladze, Chiko Kazbeli, and Dursun Imnashvili.

This modern Russian artist’s artistic leanings were evidently encouraged from a young age, and he graduated from the Tbilisi Academy of Arts in 1958 with a concentration in painting. Already a controversial figure while still in school, Tsereteli’s graduating work entitled A Song about Tbilisi was not accepted by the then-Soviet Academy, for it was believed to run counter to the “conventional elements of the broader artistic culture.” Bowing to academic pressure, Tsereteli hastily produced Portrait of a Sportsman in two weeks, and received his degree.

While in attendance at the Academy, he often labored for twelve to sixteen hours a day, and worked with Georgian artists Tengiz Mirzashvili, Givi Kesheleva, Kote Chelidze, and Nelly Kendalaki. He later went on to form acquaintances with famed painters Picasso, Chagall, and Dali. Shortly after graduation, in 1959 he displayed his works at the Transcaucasus Exhibition, alongside those of artist T. Sakhalov and Azeri artist T. Narimanbekov.

Tsereteli first found employment with the Institute of Ethnography and Archaeology at the Georgian Academy of Sciences. During his time at the Institute, he honed his artistic skills and had the opportunity to closely study folk art and the details of historic Georgian architecture. He was afforded the opportunity to work under the tutelage and guidance of Georgiy Chitaya, a Georgian ethnographer and historian.

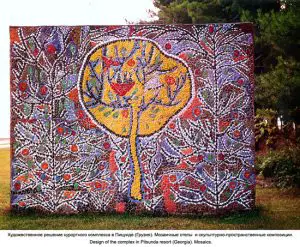

He began to distinguish himself early on in his career during the late 1960s, and created several mosaics for the resorts at Adler (located near Sochi, Russia) and Pitsunda (now in the breakaway region of Abkhazia), as well as for the cities of Tbilisi (now Georgia’s capital) and Ulyanovsk (along the southern end of Russia’s Volga River).

Upon seeing Tsereteli’s works in Adler, the famous Mexican artist David Alfano Siquerios noted, “I think that he has entered boundless spaces of art of the future, which combine sculpture and painting.” Tsereteli’s willingness to experiment in stained glass and cloisonné enamel contributed to his success in designing architectural and landscape ensembles, and he used several enamel panels while adding decor to the Brazilian, Portugese, Japanese, and Syrian embassies in Russia.

However, during the 1970s, Tsereteli turned his attentions to works executed in metal, which was to perhaps be a foreshadowing of several of his better-known works today. His work was featured on a relief of the Izmailovo hotel designed for the 1980 Moscow Olympics, and in 1979, a monument known as Happiness to the Children of the World was erected in New York in honor of the Paralympic Games.

World Fame and Infamy

Although he was educated as a painter, outside of the territory of the former USSR, Tsereteli is perhaps best known for his monuments, which can been seen in the United States, England, Spain, Italy, France, Israel, Japan, and Russia. He began monumental work as early as the 1960s. Perhaps his most controversial piece is the three-hundred-and-twenty-two foot steel, bronze, and copper monument to Tsar Peter the Great, which now resides on a man-made island in the Moscow river. Erected in 1997, the statue has both its supporters and detractors, and it has even provoked enough attention and ire to rank tenth in VirtualTourist’s 10 Ugliest Buildings and Monuments. Among its critics is sculptor Grigory Shpigelsky, who notes that “the statue must go, and there is no question about it because it doesn’t belong here in the first place…It is so out of place here and so immense that it completely dwarfs the historic environment in its vicinity, which no monument should be allowed to do in a city like Moscow.” Other critics have noted that it bears a striking resemblance to a monument to Christopher Columbus that Tsereteli attempted to present to various American and European cities, with no success. Although Tsereteli enjoyed the patronage of former Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov, with Luzhkov’s dismissal he too fell from favor at least on the city level, and was fired from his position as advisor to the Moscow city government by new mayor Sergei Sobyanin in February 2012. Sobyanin also considered removing the statue to Peter, but decided against it when it was discovered that it would cost some two million dollars to dismantle it completely and transport it away.

In 2004, he unveiled a five-meter high statue of Vladimir Putin posing in judo gear, but rather than the acclamation he was surely expecting after two years of work, it was met with withering Kremlin commentary. “We did not expect such a well-known and successful artist to do such things. He should know better than anyone else that President Putin is extremely negative about such things. We are sure that this work will not be displayed anywhere but in the palace of the sculptor’s house,” stated official Kremlin sources.

Tsereteli has not only raised the ire of Russians, but of Americans as well. His ten-story monument To The Struggle Against World Terrorism was presented to the United States and installed in New Jersey in 2006. Clad in bronze, the sculpture portrays a teardrop and includes the names of all those who perished in the 1993 and 2001 World Trade Center attacks. The sculpture was initially rejected by the arts community and moved to a more discrete location. All the same, it has received the dubious honor of being ranked by Foreign Policy magazine as one of the top ten worst politically-influenced monuments.

However, many of this modern Russian artist’s works have been well received. During the late 1990s, he was involved with the rebuilding of the city’s Christ the Saviour cathedral, originally destroyed under Stalin’s orders, and designed the Manezh Square and Okhotny Ryad complexes near the Kremlin. He has also contributed to the war memorial on Poklonnaya Hill in Victory Park, Moscow. Internationally as well, his statue of St. George in Tblisi and his statues of Balzac and John Paul II in France have been well recieved by most onlookers.

Tsereteli appears as unstoppable as he is controversial. For all his detractors and critics, he has served to contribute immensely to the Georgian and Russian art scenes and even greatly defined the look and feel of much of Moscow itself. His works can be seen the world over, for better or for worse. He is truely an artist to know.

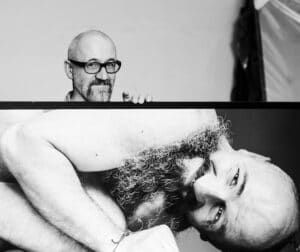

Igor Moukhin – Photographer

By Taryn Jones

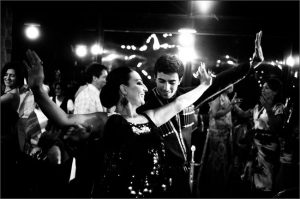

Considered to be one of Russia’s most brilliant contemporary photographers, Igor Vladimirovich Moukhin was born in Moscow on November 19, 1961. Although he realized his passion for photography at the age of 16, he worked as a heating technician and yard cleaner for several years before actively pursuing an artistic education. Finally, between 1984 and 1985, he attended classes at the studio of Alexander Lapin, a prominent Muscovite photographer who organized the “studio of artistic photographers” in Moscow State University’s House of Culture between 1985 and 1987. From 1987 onwards, Moukhin regularly held personal exhibitions of his work. He spent several years photographing rock musicians of the Soviet underground music scene during the Perestroika years of the 1980s, a decade that was to prove instrumental in his work’s growth. Moukhin quickly became known for his portraits of renowned musicians Viktor Tsoi, Boris Grebenshikov, and Petr Mamonov among others.

It has been said this modern Russian artist was fortunate enough to find himself in the right place at the right time. He began work during Perestroika and Glasnost, and his rise to prominence traces the waning years of Communism and the blossoming of new Russian capitalism. He began work as a free-lance photographer in 1989. In 1988, his work was published in Artemy Troitsky’s work “Back in the USSR: The True Story of Rock in Russia”. In 1990, his work was published in another of Troitsky’s works, “Tusovka: Who’s Who in the New Soviet Rock Culture”. Moukhin photographed a fading subculture, and, while collections of his work sell for tens of thousands of dollars today, he did it only for art’s sake.

Beginning at the onset of perestroika in 1985, Moukhin’s work was displayed and published not only in the Soviet Union but abroad. In 1988 the onset of his collections Fragments and Soviet Monuments shot him to prominence amongst the leaders of the new era of Russian photography. Fragments, which features details of Soviet propaganda posters and other Soviet artwork, is typical of some of Moukhin’s work, which turns Soviet symbolism on its head by highlighting the transient, fading nature of art that was designed to inspire and unite a nation. Through Moukhin’s gaze, the now destabilized symbols lose their potency. The Fragments series coincided with the West’s rising interest in early Soviet posters, such as those designed by Alexander Rodchenko, the co-founder of the Constructivist movement.

Moukhin was an original member (1989-91) of the group “Immediate Photography” (Группа «Непосредственная фотография»), founded by fellow artist and photographer Alexei Shulgin in Moscow as a movement against ideologically stereotypical Socialist Realist photographs. Аt the time, Moukhin was shooting his 1985-1989 series, Young People, which featured the youth of Moscow in everyday situations, from communal shower rooms to arm wrestling competitions and groups smoking in bars. The subjects of Young People were ordinary youths, ranging from the downright nerdy to pseudo hippies and punk rockers who wouldn’t look out of place in the West. It was this style of photography that attracted critics’ attention, as it showed the world in the raw, without filters or interpretations. It soon became clear to those in the art scene that Moukhin had the ability to adeptly grasp the paradoxes of nature and mankind.

It has been said that Moukhin’s work has not only great artistic, but also great documentary, value. Many have claimed that he is actually more talented at visual storytelling than are many of today’s professional photojournalists. Sometimes it is unclear whether he is a photojournalist working within the framework of modern art, or a modern artist working within the bounds of photojournalism. It is this unique vision that has contributed to his popularity. His work has a certain effortlessness and casualness about it, although nothing he creates is purely accidental. Many have, in fact, called him a sniper, due to his propensity to hunt for details in order to attain perfection.

It is this talent for capturing details that contributes greatly to his popularity. Not only was this modern Russian artist in the right place at the right time to memorialize the collapse of the Soviet Union and the rise of New Russia, but he found himself in Georgia two weeks before the outbreak of the 2008 war. Again, in keeping with his signature style, his subjects are captured without the appearance of staging: smoking, drinking, swimming in the sea and playing chess. When one considers that many of the images were taken less than a month before the outbreak of hostilities, they are cast in a particularly poignant light, as Georgians bask in the fading days of a peaceful summer.

Although many Russian artists and photographers remain largely unknown outside of the former Soviet Union, Moukhin has risen to popularity and renown abroad. In 1999, he received a grant from the Parisian mayor sponsored by the French Fonds National d’Art Contemporain (The National Fund for Contemporary Art) in order to produce a work commemorating the turn of the millennium. At this time, he undertook a series known in English simply as Paris, which shows that there is more to the famed ‘city of light’ than just the iconic Eiffel Tower. For example one shot portrays a drunk with his pants wide open. Typical of his work in the Soviet Union and Russia, Paris is a mirror held up to the city and its youth.

Since then, Moukhin has been far from a stranger on the French arts scene, as several of his works from the series Soviet Monuments, Benches, Fragments, Soviet Children’s Playgrounds, Night Moscow and Provinces, among others, were displayed in 2007 at the Parisian art space, La Maison Rouge . He has also had work hung at Paris’ Le Galerie Carré Noir. Rather unusually for many modern Russian artists, Moukhin’s work has not only been displayed in France but elsewhere worldwide. Other countries of exhibition include the Netherlands, Latvia, Denmark, France, Austria, Sweden, China and the United States.

This popularity has led to several awards and much recognition, both at home and abroad. This modern Russian artist has been a member of the International Federation of Artists since 1994, and in that same year, he received the “Man of Art” State Prize of Russia. In 1996, he spoke at the Fourth International Conference of Photography in Riga, Latvia on the topic of “The Image: A Phenomenon of Everyday Culture”. He has taught at the Independent Academy of Moscow and the Independent Academy of Photographic Arts in Kiev. A collection of forty-one gelatin silver prints in the series entitled My Moscow and Monuments, taken between 1989 and 2004, was recently estimated at a worth of £10,000 to £15,000 ($16,000-$24,000).

Moukhin’s photographic talent continues to garner increased popularity and international attention. His photojournalistic talent for capturing everything from bored Soviet youth to French lovers has gained the attention of art critics worldwide, but it is his true artistic talent that fuels his popularity. Finding himself ‘in the right place at the right time’ he has recorded the fall of the Soviet Union, the blossoming of the new Russian Federation and the continuing struggle for the establishment of stable nationhood. His acute sense of photojournalistic duty and artful composition has captured mundane moments and turned them into a representation of history, and has made a mockery of Soviet symbolism. His way of viewing the world – completely without filters – has dispelled myths about the Russian people, and has reflected our world to us without a romantic or critical eye.

Dmitry Konradt – Photographer

By Kristin Torres

Today, Dmitry Konradt is an artist who specializes in abstract photography of urban life, architecture, and organic shapes. The textures of cement block walls, the geometry of spiral staircases, the beauty in decay of abandoned buildings – Konradt shoots it all.

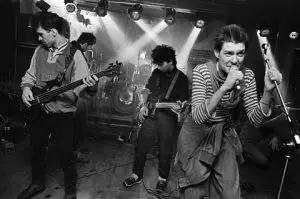

But in the 1980s, Konradt had very different subject material. He was one of the Soviet Union’s foremost rock photographers, documenting the growing St. Petersburg underground rock scene, creating a visual history of one of the most dynamic periods in Russian music. This modern Russian artist, born in Leningrad in 1954, came of age during the advent of Beatlemania, which the USSR wasn’t immune to, however the Soviet leadership tried to suppress the fad. As rock music caught on and found its audience, new bands sprung up, taking their cue from Britain’s Fab Four and Western rock ‘n roll – and giving Konradt motivation to pick up a camera.

The Soviet government had attempted to regulate music in the country by establishing a state-run record label called Melodiya, thereby pushing underground the unsigned, unofficial rock acts. However, through the 70s and 80s, Soviet citizens found that they could increasingly make, record, duplicate, and distribute music one their own with the help of newly-introduced cassette tapes and other technology. Despite governmental restrictions on bands unsponsored by the state, rock ‘n roll found its footing in the USSR and created intrigue with its brand of raucous music that would later become an outlet for social criticism and a vehicle for cultural shift. Back then, as the music scene was experiencing its first waves of rock’s influence, Konradt says “a man with a guitar looked like someone carrying a Kalashnikov (assault rifle) in the street.”

The intention behind the restrictions was to keep Western influence and values out of the Soviet Union. But in 1981, the state allowed the first legal rock club to open in Leningrad – called the Leningrad Rock Club – and Konradt saw his opportunity to make full-time what had formerly been just a hobby. This easing – thought not complete repeal – of restrictions encouraged more bands to join the scene, boosted by the “legalization” of rock and the fact that Melodiya had begun signing a few rock acts, allowing these acts to legally perform and distribute their music.

The largest rock club in the Soviet Union, the Leningrad Rock Club was overseen by the KGB, but still became a place for dissidence. The club drew a loyal crowd that participated in helping to select and support certain acts, and operated on a membership system. In its retrospective about the club, Russian Reporter magazine says the club was “the first successful experiment in creating a non-Soviet society within the Soviet Union – a kind of model for “another Russia.” Here, artists, poets, journalists, and photographers like Konradt were able to gather and in a way participate in a form of rebellion and individuality not celebrated, but now partially tolerated, by the state. In another Russian Reporter retrospective of important bands from this era, Konstantin Kinchev, leader of the metal band Alisa, remembered the club as a place where “[W]e all survived together. All helped and supported each other. One was for all and all was for one.”

It was this era after the legalization of the first rock club that’s the focus of Konradt’s photo exhibition “From the Rock Archives of the 1980s.” Open now through June 30 at the Timiryazev Library, the collection boasts nearly 30 of Konradt’s favorite images from the era, including images of rock giants Viktor Tsoi and Kino, Akvarium and its now legendary front man Boris Grebenshchikov, DDT, Sergei Kuryokhin’s Pop Mechanics, and many more.

Today, mega groups like Kino occupy a special place in the hearts of many who grew up in the “golden age of Russian rock,” and graffiti reading “Kino lives” and “Tsoi lives” can be found in many Russian cities. But their genesis came as the Leningrad Rock Club was just opening its doors, and as this modern Russian artist was delving deeper into his photography. With this new exhibition, viewers can see giants in the making.

Uninspired by what this modern Russian artist says is a lack of originality and innovation in today’s Russian music scene, Konradt is no longer a club photographer, focusing on his abstract urban photography. “I am into different things now,” he told the St. Petersburg Times. “But I don’t renounce (this part of my work). It’s an important part of my life.”

Grebenshchikov, leader of the still-active Akvarium (though he is the only original member), remarked to Russian Reporter, “Now, everything is different. Russia is changing and music is changing. But it (Russian rock) will always be there, as long as there is a Russian people and a Russian language.”

Marina Fedorova – Painter

By Corinne Hughes

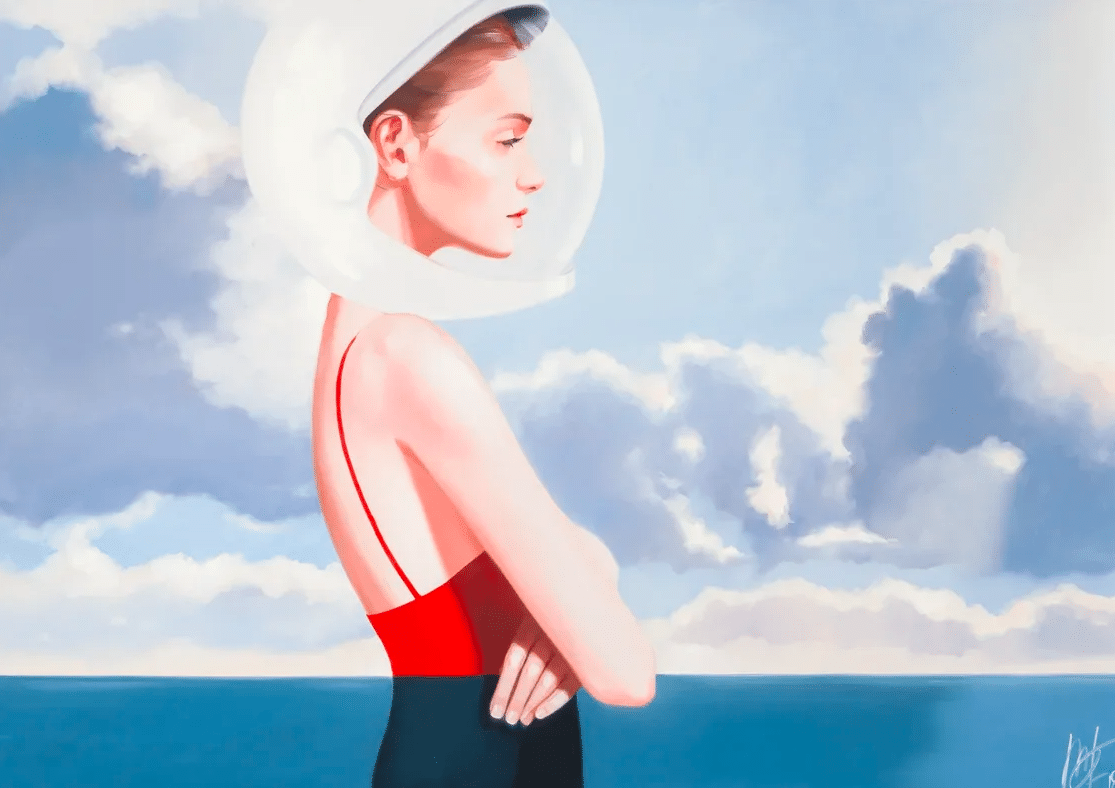

Marina Fedorova is a young modern Russian artist. She graduated from the Stirliz Fine Art School in St. Petersburg when she was 15. She then studied design at N.K. Roerich Art Academy, which is known for its exceptional design alumni. After graduation, she went on to study in the new fashion design department at Muchina Fine Art Academy, one of the most reputable art academies in the country. After graduating in 2006, her career as an artist took off, including exhibitions in the art fairs Art-Moscow and Art-Paris, as well as recognition in Forbes magazine as “one of the most promising young artists in Russia.”

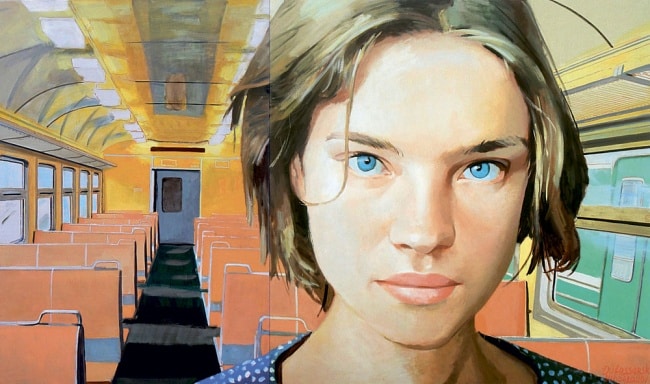

Non-Random Connections is a cinematographic collection of paintings, each appearing to be a paused frame amidst greater physical and emotional movements within a story. For the month of April, 2012, Marina Fedorova’s exhibition of Non-Random Connections compliments the reputation of the Lazarev Gallery for exhibiting paintings with sculptures, sound, and some well-planned lighting effects.

Fedorova uses text to create stories for her portraits of women walking, undressing, or looking away from the viewer to a man or the absence of one. Chunky, broad paint strokes of red, black, and white capture the central focus of the paintings, while the edges often remain unrefined, dripping, or smeared, which creates a sense of incompleteness. The use of red is elemental to each piece as an emotional force, defining the attributes of story within the portraits. The addition of plastic sculptures deepens the atmosphere of the pieces, creating powerful, fantastical extensions of the world within the painting. The use of lighting is also interesting. Directly focused on the paintings, the bright lamps spotlight the images amidst a rather dark gallery, setting the viewer apart in a voyeuristic view. Throughout the gallery, heavy panting and a young, female French singer can be heard from speakers, adding a sensual element to the exhibition.

When You’ve Gone Away… encapsulates all of these things and is the first painting one sees in the exhibition. Half the canvas is white, the piece’s title written in black cursive at the center. The rest is a portrait of a girl in a bra, facing away from the viewer to a disheveled bed and the image of a man in a suit walking away, the sway of his hand the only clearly visible part of him. The entire portrait is smeared like an unfocused photograph. In front of the painting hangs a carved, red, plastic heart with a mass of veins extended outward in a root-like circle. This modern Russian artist has created an entire piece that evokes emotions of longing, isolation, and unbridled love.

Butterflies is one of the most striking pieces in the exhibition. Fantastical, visceral, and absolutely intimate, the focus of the portrait is on a woman’s bare chest. Her head is thrown back while her two hands pull apart an opening in her chest, releasing a mass of butterflies. In front of the painting hangs a chandelier of red, plastic butterflies, each glowing from inserted LED lights. They reflect onto the painting in a brilliant red that is hard to discern from the painting. Fedorova also used her non-conforming exhibition style to express different ways of seeing. Painting-Viewer-Artist is a collection of two paintings situated in front of a mirror. The central painting shows a coffee machine with arms holding a cup of coffee. The second painting shows a person looking at the central painting. All the while, the mirror reflects these images. The real viewer in the Lazarev Gallery enters the painting in this way, forced to grapple with the reality of the painting, for which there does not seem to be a definition of a beginning or an end.

Marina Fedorova is known for her quick style of painting and the ability to sell her pieces, giving her an edge in the art market for exhibitions. This modern Russian artist will turn up fairly quickly again in St. Petersburg or Paris, her two main hometowns at the moment, or beyond. She’s young, busy, and on a bright path to success.

More on Marina Fedorova below

Marina Fedorova’s Photostream

By Kristin Torres

Photography in the age of the smart phone has allowed us to become the curator of our own lives through rectangles and squares that take up space on our memory cards. Aided by this lightweight technology, we no longer need to lug cameras with us everywhere we go if we want to take pictures. Should we run into an unexpected moment in time we’d like to capture, all we need to do is whip out a smart phone – with its myriad functions and uses – and we almost never have to miss another shot.

But easy come, easy go. Our memory cards fill up and once cherished photos get deleted to make room for new ones. And when they’re gone, where do they go? Unlike film photos that we can stash in boxes under the bed or in photo albums on bookshelves, digital photos vanish into the ether once we effortlessly hit ‘delete.’ Even the photos we upload online aren’t safe from these whims, as they’re just as vulnerable as becoming permanently erased the minute we deem them embarrassing or unflattering.

This is the thesis behind Marina Fedorova’s Photostream, held at the Lazarev Gallery. This graduate of the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts has re-created an iPhone and picture gallery where audiences can arrange and delete photos at will. Standing two and a half meters high, this giant wooden version of Apple’s flagship product comes complete with 20 mini paintings on the iPhone “screen,” made to look like 20 pictures in a picture gallery.

All the usual suspects are there. The snapshot of a pretty plate of food, a fashionably dressed hipster casually leaning against a wall of black-and-white street art, a cozy bed with crumpled sheets, a day at the beach, an urban street corner – all slices of life, frozen in time in squares and rectangles on our phones.

The piece is interactive, giving viewers the opportunity to ‘curate’ their own photostream — re-arranging the individually painted squares to create a scene, tell a story, or have no narrative whatsoever. Viewers can even choose to exclude photos from their photostream, leaving unwanted (deleted) photos off to the side. Some photos even have borders like those popularized on Instagram, suggesting the “owner” of this iPhone has manipulated the pictures with filters and other decorations. The ability to edit and share our photos almost instantly has in a way changed the way we take pictures in the modern era. Photos are now not just personal mementos, but ways to communicate our personality to friends, family, and even total strangers on social networks.

What makes Fedorova’s project more relatable is that her painted “photos” don’t contain specifics. The photo of a cyclist in an urban downtown doesn’t suggest exactly where on the map that cyclist is. It could be St. Petersburg, New York, Paris – it depends on the viewer’s imagination. In one scene at the beach, a woman and a young girl converse on a dock, but one woman’s face isn’t visible in the frame, allowing a bit of anonymity and the ability for the viewer to fill in the blanks.

This theme is frequently seen in Fedorova’s work. Since 2005, the 32-year-old, St. Petersburg-born artist has painted a number of different works that draw on the idea of anonymity. In her 2010 collection Blue Beard, for example, the majority of paintings include scenes where the faces of her subjects are obscured. A woman behind a veil, a close-up of a businessman that shows only him from the tie down, a man walking in the snow shown only from the scarf down – Fedorova’s works have a way of making the viewer feel like they can be looking at paintings of anyone almost anywhere.

With digital smart phone photography, we can edit and manipulate our pictures – slices of our lives – to achieve a certain outcome that we choose to share with the world. Like the hipster in front of street art trying to look cool, the photos we share – as well as the photos we choose to not share – say something about how we want the world to perceive us. Fedorova’s lack of specifics in the faces and places she paints suggest that this want to “curate” the moments we capture and to manipulate how we’re perceived by the people we share those moments with is not an uncommon desire.

Gosha Rubchinskiy – Fashion

By Kristin Torres

For Russia’s post-Soviet youth, one of the first generations born with a kind of clean slate for presenting who they want to be and the images they want to portray, much of that expression comes through in dress.

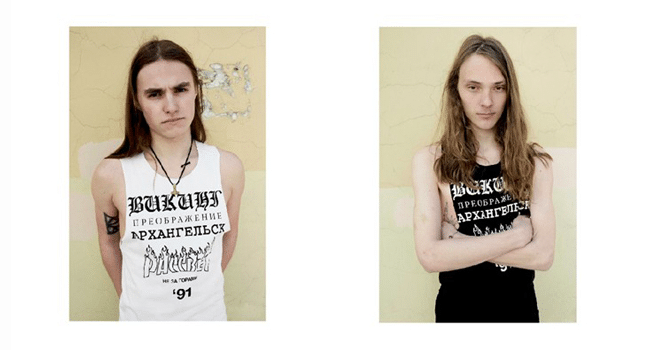

That’s where 28-year-old fashion designer, photographer, and videographer Gosha Rubchinsky comes in. He’s already made quite the name for himself in Russia’s two main cities with his eponymous clothing line, and he says his vision for clothing the emerging youth of Russia expands past Moscow and St. Petersburg. And while he doesn’t shun fashion shows or exposure elsewhere, Rubchinsky seems to care little at all about the splash he could make abroad. “Everything that inspires me is in Russia,” he told the UK art magazine Dazed in 2010. And his brand of fashion–the glossy images of his work in magazine spreads notwithstanding—is for the benefit of punks, working-class kids and those unfazed by the allure of nouveau riche sentimentality. Less fussy and certainly not runway-ready, Rubchinsky told FADER magazine in 2012, “My generation doesn’t care about luxury… I don’t want to make clothes for the rich.”

And it shows. Rubchinsky’s menswear designs are inspired by blue-collar (or even no-collar) calling cards – sports, skater culture, and punk rock. Cut-off shorts, tight T’s, distressed tank tops, hoodies, and sneakers – his fashions are a mix between Western sportswear (think Adidas and Kangol tracksuits) and a late 80’s, early 90’s punk and hardcore aesthetic. FADER put it succinctly: Rubchinsky and his friends are styled like they’re out of the D.C. hardcore scene, “though most of them weren’t even a glimmer in their parents’ eyes when Minor Threat shared a bill with Bad Brains. Speaking with Interview magazine, Rubchinsky said, “My clothing is for my friends.” It just seems that his friends must have major nostalgia for a period of fashion they neither lived through nor lived near. The aesthetic that paints most of his work almost decidedly belongs to the twentieth century West’s interpretation of punk and hardcore fashion. Now, thanks to the designer, it has a Moscow twist.

Rubchinsky was just growing up when the former USSR was experiencing waves of influence from the capitalist, consumerist West, a transitionary period when Soviet times were not quite memories just yet. He told Interview that his fashions are a way of making sense of what he and others around him had available to them. “I remember going to the countryside with my friends and dressing weirdly because there was a shortage at the time. You were only allowed one pair of Levis jeans and one tracksuit from Adidas. You wore all of this together. Not because it was stylish, but because it was the only clothes you had from the West.” Now, however, he’s able to execute more control of how he mixes pieces, creating fashions that seem to be conversations between Russia and the West.

Not all of his fashions seem rough around the edges, however. His Spring 2013 collection is clean cut, though vestiges of sportswear aesthetic are still visible: Lace-up sneakers, cotton cut-off shorts, tailored sweats, knee-high sweat socks – but all with subdued, neutral colors, a bit of a departure from his previous work that included studs, face masks, and almost an entirely black color palette.

When Rubchinsky says he’s making clothes for his friends, it’s apparent that he really means it. His clothing may look designer-made, but it keeps in mind comfort for skaters and graffiti artists, he says. It’s also of little significance to him who’s actually buying the clothes. In his interview with Dazed, he said he makes clothes for Russian youth, just as a Berlin-based designer might make clothing for fellow Germans. While his works are informed by a time and place that might not entirely be his own, Rubchinsky holds a lot of respect for his language and his country. A lot of ubiquitous sports wear in Russia is simply imported, retaining the original English slogans or print. Not so with Rubchinsky’s line. A back of a sports jacket reads “РОССИЯ,” not “Russia.” When Western culture flooded the former Soviet Union, many young people reacted by becoming more nationalist. This nationalism now creates an aesthetic and mentality distinct to Rubchinsky’s generation. “All these young people who were born after 1991 – I realized that these were the people I wanted to design for,” he told Dazed.

In accordance with that philosophy, Rubchinsky’s collections are usually debuted in a way suited for his generation, eschewing traditional avenues like runway shows or Fashion Weeks. His collections are instead debuted through his own video work and photography, which includes portraits of his friends wearing his fashions, as well as documentary-style videos of his friends skateboarding. His Spring 2010 collection was debuted with a performance and a video shown in Moscow in an church-turned-recreation-center, where models worked out or skated in his gear instead of walking down a runway. Other collections have been debuted in similar performances and videos, putting a youthful, anti-establishment twist on the world of contemporary fashion.

Rubchinsky collaborated with Addias and Burberry during the 2018 FIFA World Cup, truely earning him a stage viewed by the world to display his often football-inspired fashions. Despite this, however, his inspiration and most of his business efforts remain in and tied to Russia.

Also in 2018, this modern Russian artist shuttered his eponymous brand, announcing that “what I wanted to say with it, I said” and that it was a good time to start something new. Since then, he has started Rassvet, a new clothing line, together with Tolya Titayev, a Russian skateboarder. Shortly thereafter, he announced another new project, GR-Uniforma, a clothing line launched with British help.

He has also since tried his hand at costume design for North Wind, a film written and directed by Russian playwright Renata Litvinova and which featured music written by Russian pop icon Zemfira. The film, loosely based on a play by the same author, is about a magical land where matriarchy reigns.

Although now branching out in terms of his creations and marketing reach, Gosha Rubchinskiy remains tied to Russian culture and is still producing fashions for youth.

Find More Modern Russian Artists

(includes current article)

Russian Protest Art that Isn’t Pussy Riot

When most think of Russian protest art today, they think immediately of Pussy Riot, the long-famous, all-female punk movement. These women have, since their “punk prayer” launched them to international notoriety, been heavily covered in the English-language press and heavily studied in English-language academia. However, Russian protest art is a diverse genre with a long […]

Gorky Park and Garage Museum of Modern Art in Mocsow

Gorky Park and Garage Museum of Modern Art in Moscow Poster Child of Russia’s Urban Revitalization Open 24/7 Free Entrance, Bring Cash for Food, Bike Rentals, etc. For several years now, Russia’s federal government and the city government of Moscow have worked together in an attempt to revitalize the capital city, with a particular focus […]

Moscow Museum of Modern Art

This MMOMA is a group of museums that house a range of contemporary artists and installations. This art is from the entire second half of the 20th century forward. Some employ traditional methods with a modern feel, and there are also exhibits that really push the boundaries of what we consider art. Some gallery space […]

10 Contemporary Russian Painters Worth a Look

Levitan, Shishkin, and Aivazovsky, among many others, are names known to every well-educated person in Russia and abroad. These artists are Russia’s pride. Today, too, there is no shortage of talented contemporary Russian painters. Their names are just not yet so widely known. AdMe.ru, a Russian site dedicated to Russian popular culture and advertising in […]

Museum, Complex: Combining Culture, Community, and Contemporary Art at Erarta

There’s a lot to be said about the highly political, oftentimes tenuous relationship between artists and art galleries throughout the Modern age. It can be argued that this ambivalent relationship has its origins at the founding of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris in 1648. For centuries, an artist’s reputation was vaulted […]

Moscow’s Modern Dance Movements

In Moscow, a close community of performers and dancers exists that examines and explore body movement. Some choreographers define their work as “modern dance,” while others call their art “nonverbal dramatic theater.” Some choreographers and dancers attempt to avoid definition all together, explaining their art more loosely with terms like “total body movement,” “improvisation,” “free […]